In honor of Native American/Indigenous and Alaska Native Heritage Month, Dr. Irina Feldman’s Spanish 324 Class, Images of America, has collaborated with the Davis Family Library to develop a display including works that commemorate the many peoples belonging to these groups throughout the Americas. Visit the Davis Family Library to see the display and read more about how it all was shaped below. We thank Marlena Evans, Caleb Turner, Alaina Hanks, Oshin Bista and all the unseen laborers and sponsors who make these projects successful.

The display in the Davis Family Library lobby will be staffed by students from the class on the evenings of November 6th, 7th and 8th to answer your questions on this theme. Plan to join us the evening of Monday, November 27th when Chief of the Abenaki Don Stevens will join the Middlebury College community for a talk on contemporary life in Vermont as a person of indigenous heritage. Also, stay tuned for Dr. Brandon Baird’s talk, “Unequivocally Authentic: Mayan Language and Identity in Modern Guatemala,” in the Carol Rifelj Lecture Series hosted by the Center for Teaching, Learning & Research on November 29th. The site go.middlebury.edu/calendar has more details.

Dr. Irina Feldman (center, in scarf) and her students from the Spanish 324: Images of America class pose for a photo in their classroom. They have contributed their energy to commemorating Native American/Indigenous & Alaska Native Heritage Month and selected works for the Davis Family Library display.

Participants; Hometowns; Roles @ Midd; Times @ Midd:

This is the cover art used for a book titled The Original Vermonters by William A. Haviland which speaks of the Abenaki Indians, groups of indigenous peoples residing in what we now know as various parts of New England and Canada. Chief of the local Abenaki, Don Stevens, will visit Middlebury College on November 27th to speak to the community. Follow go.middlebury.edu/calendar for more information.

Katrina Spencer; Los Angeles, California; Literatures & Cultures Librarian; 9 months

Irina Feldman; Saint Petersburg, Russia (Leningrad, USSR); Assistant Professor of Spanish; 8 years

Peter Thewissen; Kent, Ohio; International Politics & Economics Major; 2 years

Rae Aaron; Phoenix, Arizona; International Politics & Economics Major; 4th semester

Pedro Miranda; Scarsdale, New York; International Politics & Economics Major; 4th semester

Rachael St. Clair; Minnetonka, Minnesota; Neuroscience Major; 4th semester

Sam Valone; Wayland, Massachusetts; Economics Major; 2nd semester

Sophie Taylor; Los Angeles, California; Museum Studies Major; 3rd semester

George Valentine; Montpelier, Vermont; Environmental Studies/Conservation Biology Major; 4th semester

Ella Dyett; Brooklyn, New York; Psychology/Spanish Major; 3rd semester

Holly Black; South Portland, Maine; Neuroscience/Spanish Major; 4th semester

Kiera Dowell; Charlotte, North Carolina; Mathematics/Spanish Major; 3rd semester

Annika Landis; Hailey, Idaho; Environmental Studies/Human Ecology 2nd year

Lesly Santos; Chicago, Illinois; Classical Studies Major; 3rd semester

Hannah Seabury; Santa Barbara, California; International and Global Studies major; 4th semester

Wynne Ebner; Chevy Chase, Maryland; History Major; 5th semester

Greg Dray; Guilford, Conneticut; Computer Science Major; 5th semester

Melisa Topic; Chicago, Illinois; Psychology/Spanish Major; 5th semester

Kyle Wright; Denver, Colorado; American Studies; 4th semester

Ellie Carr; Ainsworth, Nebraska; International and Global Studies; 5th semester

How does the course content for Spanish 324: Images of America relate to the theme of the display?

Katrina: Irina and I happened upon a happy intersection between discourses we wanted to highlight this semester. I wanted to underscore Native American/Indigenous & Alaska Native Heritage Month, which, here in the U.S., is often celebrated with a relatively closed geographical region in mind. Irina reminded me that when we talk about indigeneity in the Western hemisphere, it absolutely makes sense to include the regions we now know as Canada, Mexico, Central and South America and the Caribbean. The Abenaki, the Mohawk, the Sioux, the Cherokee, the Inuit, the Aztecs, the Maya, the Nahua, the K’iche’, the Aymara, the Tupi, the Guaraní, the Taíno, the Arawak and many, many more groups share historical experience that cannot be seamlessly divorced by the imagined borders we have applied to modern-day regions.

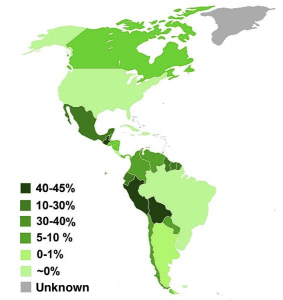

A map borrowed from the Wikipedia entry for “Indigenous Peoples of the Americas” depicting indigenous populations from what we know today as Greenland to Argentina with the land masses darkened in gradients to show indigenous population density. Guatemala, Peru and Bolivia are the most heavily shaded with 40-45% of the populations labeled as indigenous.

Pedro/Sophie/Hannah: In Images of America, we explore how America has been represented by writers and artists from both colonial and indigenous perspectives. We seek to study how the continent was imagined from different points of view, and how these perspectives shaped (and still shape) the culture and identity of America. We strive to challenge our stereotypes and associations of the word “indigenous” through our course material and readings, and explore both sides of the narrative in a world where most of history is written by colonizers. Our goal of constructing this display in the Davis Family Library, as well as inviting Chief of the Abenaki, Don Stevens, to speak at Middlebury, is to educate the Middlebury student body on the themes we have learned from our class, especially the historical oppression and misrepresentation of the indigenous American experience.

How did you contribute to this display?

Katrina: My job was to tell the students in the class what has worked for me in the past inasmuch as shaping displays, to be open, and to direct the team to good contacts to help carry out the necessary work. My supervisor, Carrie Macfarlane, models this for me all the time. I wanted students to be realistic about timelines, conscientious about scope, but most of all, confident in their ability to carry a significant project forward. I lent advice in steering but they did most of the hard work.

Rae/Wynne: As students in Images of America, our professor and library were our resources to compile documents and materials ranging from audio and film to novels and children’s books. We pulled books from Davis Family Library and ordered others online which we identified as offering an unique perspective or valuable information. Each student contributed at least two sources that they deemed relevant and useful contributions to conversations surrounding indigenous groups in America. We then organized our sources based on geographical origins and collaborated with our peers to create a bookshelf display with visuals that offer the greater Middlebury community access to Indigenous history and culture. We hope this display will give the community the tools to recognize the importance of Native American heritage and celebrate its many elements at Middlebury.

This screenshot depicts the homepage of Indigenous Peoples: North America, a digital archive in the libraries’ collection rich in primary sources. To find it, visit go.middlebury.edu/databases and search entries under the letter “I” for “Indigenous.”

Describe some of the limitations the class encountered in shaping this collaborative effort.

Irina: The biggest limitation is, of course, the absence of the first-hand indigenous voices. When working on our sources and on analyzing the class materials, what we often find is a European writer talking about the indigenous experience (such as Columbus or Padre [Bartolomé de] Las Casas), or an anthropologist translating the indigenous voice for a wider public. As a class, we are scholars of indigenous experience of Latin America, but none of us is indigenous. The students have been brainstorming on how to compensate for this always-mediated condition of indigenous testimony, and I will let them speak about the solutions they found to this limitation.

George/Annika/Ella: Given that so much of the available literature on the subject is narrated from the European point of view, our challenge was to bring some of the less common indigenous viewpoints to the forefront. The first and best way to do this, we agreed, was to allow them to speak for themselves. That’s why we have invited Chief Don Stevens of the Nulhegan Abenaki to give a talk about his tribe’s history to members of the college. Another limitation we encountered was developing this project and all that we wish to accomplish within such a short time frame.

How can we learn more about the local group called the Abenaki?

Holly/Peter: There are many resources available both online and around Vermont that we can use to further our knowledge of the Abenaki people. For example, the Vermont Abenaki Artists’ Association works to both preserve traditional Abenaki art and to create contemporary artistic expressions of their culture. This group travels around the US and Canada, and even Germany, to give demonstrations that share the presence of Abenaki culture. Their website can be found here at www.abenakiart.org. In addition to this site, the Abenaki Tribe at Nulhegan-Memphremagog maintains a separate website at www.abenakitribe.org with information about the history and current state of the Tribe, as well as links to other sources of information on the web. We encourage anyone who is interested in the Abenaki to visit these resources, or better yet attend the talk by Don Stevens, Chief of the Abenaki, to learn about the tribe firsthand.

Katrina: The cover art near the top of this post for The Original Vermonters is an invaluable text with highly accessible writing. To educate ourselves on the Abenaki, the entire class received scanned copies of chapters 5 and 7, respectively “At The Dawn of Recorded History” and “Survival and Renewal: The Last Two Hundred Years.” Moreover, the Ethnic Studies Research Guide offers a variety of entry points for studying indigenous peoples. Librarian Brenda Ellis, liaison to the history department, has also highlighted the U.S. History Research Guide, also rich in resources for research purposes.

What did you learn about other indigenous populations in the Western hemisphere?

Holly/Peter/Rachel/Sam: Many indigenous populations understand society as operating in a state of relatedness whereas typical Western culture believes in compartmentalization and individualism. The environment, objects, and people are closely linked, and this connection is reinforced by law, kinship, and spirituality. This is a holistic and fluid way to observe society; connections supersede categories and pressure is relieved from one single object or person to perform a specific, isolated role. In this manner, indigenous populations view nature as an economic system that governs society. However, this form of society is threatened when it comes into contact with modern, capitalist societies. Governments are increasingly focusing their attention on economic development and modernization, taking precedent over indigenous autonomy and culture.

Katrina: There are two major points. First, I read University of Illinois professor Debbie Reese’s “American Indians Are Not “People of Color,” which blew my mind. It is succinct and makes it clear that many of the groups we’re celebrating belong to sovereign nations which makes their political groupings different from those of African Americans, Asian Americans and Latinx Americans. Second, additional readings reinforced the idea of indigenous people being intimately tied to the land and the goods it produces, which underscored the importance of land rights and the disastrous impact that historical relocations to reservations have had on communities and ways of life.

Depicted is the cover art for the book 1491 by Charles C. Mann that describes cultures and society in what we now know as the “Americas” preceding Christopher Columbus’ arrival. Find it through MIDCAT in the Davis Family Library collection.

What specific resources did you find that you feel others should know about related to these topics?

Katrina: 1491 and its sequel 1493 are historical works with deftly compelling titles. Essentially, they pose the questions, “What was life, culture and society like in the Western hemisphere before Christopher Columbus’ arrival and how was it indelibly impacted thereafter?”

Melisa/Mimi/Greg: The Arts of the North American Indian: Native Traditions in Evolution is an excellent book for understanding the roots and development of various art forms utilized by Native Americans. It is especially interesting to look at the impact of those art forms on contemporary art practiced today. Another resource, My Home As I Remember, is a collaboration of over 60 Native American female authors, poets, and visual artists where they tell their respective stories of home and origin. Not only does this book bring together native women from all over the world but it also provides a resource for others to learn about different native cultures and traditions.

What do you hope the Middlebury community will gain from these efforts?

Depicted is the cover art for The Arts of the North American Indian, edited by Edwin L. Wade. Find it through MIDCAT in the Davis Family Library collection.

Kiera: With issues such as cultural appropriation for costume parties, problematic mascots, and even the celebration of Columbus Day still widely prevalent in our society, the humanization and normalization of indigenous peoples through exposure to indigenous culture could go a long way to increase awareness of how these issues directly affect the perception of indigenous people in our society, as it is much more difficult to intentionally disregard the feelings and opinions of people with whom you feel connected. At Middlebury in particular, where the large majority of students are white, the issues facing people of color in general (and indigenous Americans in particular) are regularly addressed but not fully understood by the majority of the population, and hopefully the increase of education surrounding a variety of issues facing the indigenous and POC (people of color) would allow white students, and thus the Middlebury community as a whole, to be more empathetic with people against whom our society is prejudiced.

Katrina: As a society, we err when we think of the default prototype for an American as a white, Christian, able-bodied, heterosexual, cisnormative male. For the rest of our lives, I want us to aggressively challenge that notion that exists in our collective imaginary. Remembering the past and the violent ways in which this country was born aids that trajectory and helps us to acknowledge the legacies of the past and our responsibilities in the present.

Depicted is the cover art to My Home As I Remember, edited by Lee Maracle and Sandra Laronde. Find the e-book through MIDCAT in the Davis Family Library collection.

Kyle: Because Native people and first nations have historically been excluded from conversations of racial, socioeconomic, and disability justice, it is particularly important to emphasize the histories, experiences, and cultures of those people to increase representation in spaces, like Middlebury, that have historically spotlighted the experiences of white, wealthy, able-bodied, cis-hetero men. This work may help to generate a greater degree of discourse at Middlebury surrounding how certain people are systematically excluded and marginalized along lines of identity on and off our campus.

Lesly: With a population that consists of mostly [North] Americans, Middlebury could use this program to raise awareness of this group of people that has been separated from its land and marginalized from social recognition. In this aspect, it is important for people to remember the original inhabitants of this land and its history, especially in our modern-day politics. The cultural wisdom and social components that the Native American people possess could aid philosophical growth and recognition of the culture that lives within us that hardly anyone speaks about. This may also be something that can support mindfulness for inclusivity and respect towards different cultures/people.