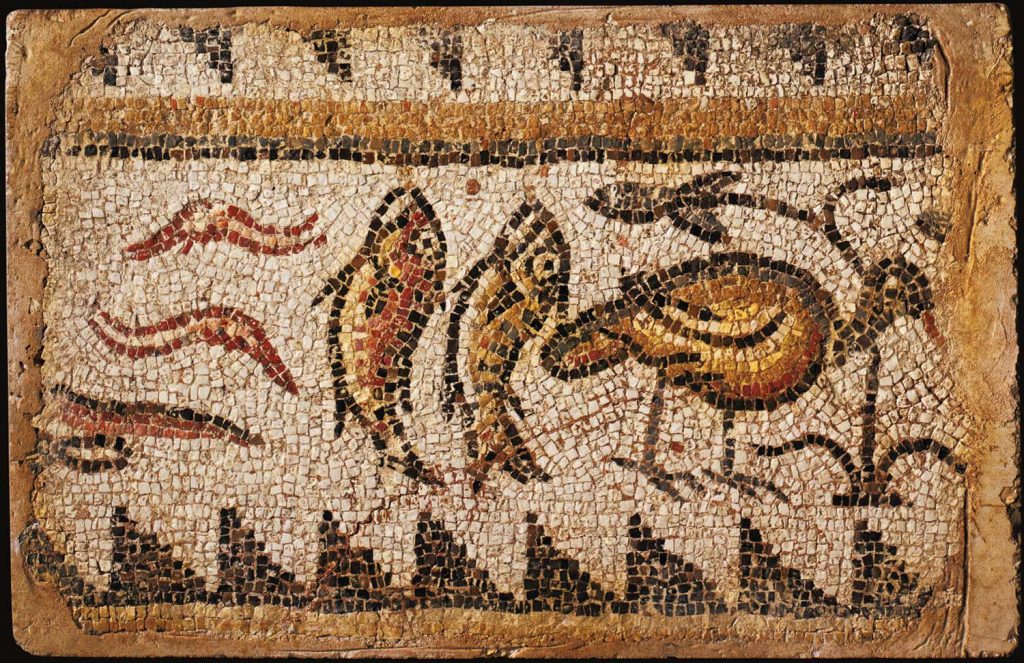

During a 2019 re-installation of an Early Byzantine floor fragment, Museum staff invited three members of our community—an artist, an ecologist, and an archaeologist—to offer their perspectives on this mosaic. Recognizing that there are many ways to interpret a single work of art, we invite you to add your voice to this dialogue by sharing your thoughts, feelings, and inspirations in the comments. We would also welcome your feedback relative to this sort of forum as we hope to add more works of art and continue a hybrid in-person/online dialogue when the museum reopens.

We look forward to reading your responses.

You might wonder why this fragment of a floor mosaic, produced for a lavish villa in Syria, depicts the fauna and lush flora encountered hundreds of miles away in and around Egypt’s Nile River. The simple images depicted here stand for more than meets the eye, connecting three distinct geographic regions and cultures in a lineage spanning thousands of years.

During the Early Byzantine period (c. 330–700 C.E.), the area of modern Syria became a major producer of olive oil. The wealthy Syrian farmers who commissioned mosaics such as this one for their country estates were paying homage to earlier Roman mosaics, piggybacking on what they perceived as Rome’s greatness. As early as the Republican Period (509–27 B.C.E.), the Romans had likewise sought to place themselves within a longer legacy: by referencing the Nile in their art, they evoked the fabulous wealth and millennia-old civilization of Ancient Egypt.

—Pieter Broucke, archaeologist

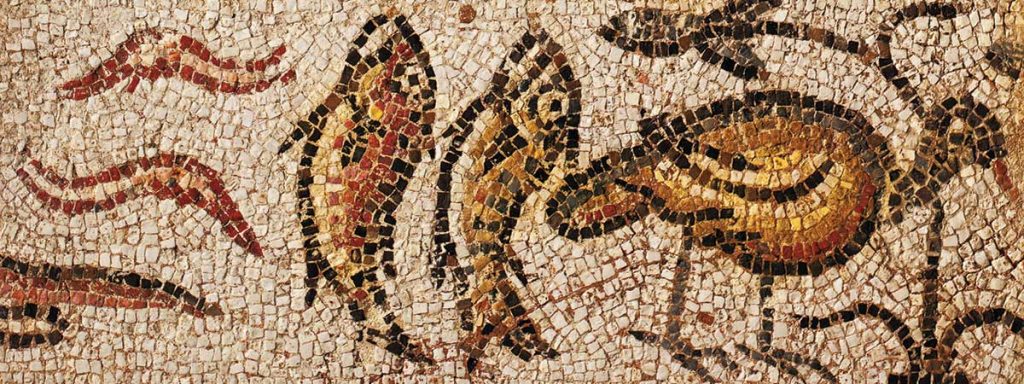

This fragment of a floor mosaic is made from small pieces of cut stone. Consummate craftspeople selected these tesserae (Latin for cubes or dice) for their color and brilliance, artfully positioning them in a cement matrix to create a durable and beautiful floor. While the stones composing the geometric border of black and white triangles are laid in a grid, the tesserae at the fragment’s center follow curved natural forms, as if to accentuate movement.

These tesserae also function as specks of paint, delineating forms through white and black, warm reds and pinks, blues, grays, and ochre yellows. Subtle harmonies of color enliven the duck’s variegated feathers, the red and pink shrimp, the undulating eel, and the speckled bellies and striped backs of the fish. Elsewhere, bold color contrasts dominate the design, as in the black and white geometric border and the black tesserae outlining the duck, fish, eel, mussel, and lotus plant.

—Kate Gridley, artist

The artisans’ choice to highlight the Nile and its associated biodiversity is likely rich with meaning. Water is life in a desert environment, such as in large portions of the Middle East (the original site of the mosaic) and northeastern Africa (the source of the wildlife depicted). Animals that are critical sources of food live in the river or are drawn to it—such as the fish and bird depicted in this mosaic—and plants that provide both food and fiber grow lush along its banks.

The abundance of water itself helps provide the basis for agriculture, and the seasonal flooding of the river replenished nutrients in the soil to maintain productivity in each year’s harvest. While it is true that many nomadic cultures thrive in drier conditions, the ecology of a river such as the Nile enabled the development of a prosperous settled society.

—Stephen C. Trombulak, ecologist

Thanks to all for sharing these interesting observations and questions. When I look at this mosaic, I find myself curious about the lives of not only the wealthy landowners who once walked on this floor, but also of the workers who laid these tiles. Or the stories of the people who harvested the landowners’ crops–the sale of which I presume generated the income that paid these artisans. On the surface, so much (though not all) of what museums collect and display (and history books record) represents the experience of the privileged few. But there is so much more to the story, often embedded right in the production and history of these luxury items. If anyone can suggest resources where I could learn more about the experience of “everyday life” in the ancient Mediterranean world ACROSS socioeconomic lines, I would be very grateful.

This is a rare example of an ancient “plat du jour “ menu, in this case, a fish starter followed by a hearty roasted fowl. This was a particularly popular selection, hence the investment in a sturdy mosaic. The images are an efficient solution to the challenge, in the multi lingual marketplace, of communicating with as many potential consumers as possible.

(Great idea to do this)

There may be something to this menu theory. Just think of the pictures used in at least one lupinaria in Pompeii.

Hmmm, a menu on the floor…. Interesting idea. It reminds me of a place to eat I visited in the eastern Mediterranean some 30 years ago. They had ambitiously installed a terazzo floor, with letters spelling–literally set into stone–what the establishment really was. However, the text read “SNAKE BAR” instead of “SNACK BAR.” Oops! It is probably still there…

As to the “menu” pictures at the Lupinar (brothel) in Pompeii, that too is an interesting comparison.

Remarkable where this discussion has ventured….

Haha, this is a really funny comment! Thank you! At some level you are right, of course: the ‘Nilotic’ border features the abundance, in flora and fauna, of the Nile valley, the delta in particular. And so much of that is edible: definitely the fowl and the fish, as well as the shrimp, eels, and clamps (these latter three, of course, are neither fowl nor fish!).

I am not so sure about the lotus being edible, but Greek myth has, of course, the famous ‘Lotus Eaters.’ Nowadays, according to Wikipedia, the term ‘lotus-eater’ denotes “a person who spends their time indulging in pleasure and luxury rather than dealing with practical concerns.”

Thank you, Briana, for your comments.

Early on, Ancient Egypt was more closely tied to the rest of Africa than to the Near East and the Mediterranean. That changed over time for both political and environmental reasons. Politically as a result of the occupation of Egypt by Near Eastern powers, then by the Greeks in the wake of Alexander the Great’s conquests, and finally by the Romans during the Early Empire. Environmentally as a result of people from the Near East fleeing droughts and moving into Egypt’s fertile valley over the course of the last millennium BCE

As to the flora and fauna, I believe the plant is a stylized and heavily simplified rendition of a lotus plant. The bird may, indeed, refer back to imagery of the ibis, a bird associated with the god Toth and now extinct in Egypt (not a surprise: there are thousands of ibis mummies!). The shrimp, clams, and eel depicted here are only identifiable because of similar representations on more finely executed mosaics. Together with the fish, the ibis, and the lotus plant, they form part of the standard iconographic repertoire for Early Byzantine Nilotic borders. Indeed, these mosaics animated the floors of Syrian country estates, and were thus meant to be walked upon. Not all tesserae are glass but those that are are so small that they, apparently, did not readily break.

When I look at this mosaic, it reminds me of those tests in school where you are supposed to figure out the pattern by guessing what comes next in the sequence of objects. Shrimp, fish, shorebird, shrimp, fish, shorebird, etc… As someone who tends to view the material world with a graphic design perspective (though I am not a graphic designer), I also see an attempt at symmetry that doesn’t quite achieve it. The geometric shapes along the top and bottom borders are not the same size; the outermost border is uneven; the horizontal lines near the top are not repeated near the bottom; the shapes and number of each creature is different; and, the stones look haphazardly placed. Despite the failure to achieve perfect symmetry, the piece as a whole works and is quite pleasing to the eye. There is order in disorder and in nature as well as art, the formula works.

I took a continuing ed NYU class on oriental carpets taught by George Anavian and he described how the inconsistencies and asymmetries in carpet designs were to make them more intellectually and visually interesting to the people who’d be in close contact with them, sitting on them. Maybe something of that here?

That makes sense, Briana. Imperfections/asymmetries/inconsistencies do seem to draw one’s attention toward an object and make it seem more one-of-a-kind. Like you, I love this exercise though I didn’t exactly write my label as a curator would!

The Japanese have the concept of “Wabi Sabi,” the aesthetics of rough imperfection. That seems to relate to imperfection and slight asymmetries being more interesting, visually, than perfection and absolute symmetry.

You could also think of this composite image as a “which element does not belong” puzzle. I would say, the lotus plant, because all the other elements are fauna, not flora, but we have to be careful: the mosaic is a fragment–it is not the entire border that would have wrapped around the room in which it was installed.

I love this exercise so much. Thank you for posting. I believe the basic label information (title of piece, date, etc.) is called the tombstone in museum parlance, which may be an interesting fact for wonkier readers.

The archaeological read made made me think of how in the late 19th century the designs of American classical architects were meant to evoke Greek and Roman architecture to make the same connection to classical heritage. As Americans gained money, power and dominance in the world, they wanted to visually show in their architecture and decor that they were also tied to that past.

Which makes me think that another read on objects such as this one would talk about the culture not reflected in it. For example, Americans wanting to tie themselves to a classical heritage wanted to tie themselves back to what they most likely perceived as a very white, superior lineage, but of course the classical world wasn’t all white. What would the non-white, non-colonial take on this fragment be (fully acknowledging that those aren’t academic or art historical terms)?

The artist’s reading of this object made me really consider its materiality. I can see how the natural color of stone created the earthy palette, which made me want to look closer at what was going on with the red. That’s glass, correct? That line of inquiry made me want to know more about glass production at the time. Is that an expensive material? How’d they get such a gorgeous deep red? Would it be technically hard to combine glass and stone in a piece like this? Isn’t glass breakable? (This was for a floor, yes?) After reading this label, I wanted to see a detail or two of the artwork to get a closer visual read on the object to see the corners and edges and such. Also, those are shrimp! Brilliant. And a nice way to segue to the ecologist’s label.

Is it possible to tell what kind of flora and fauna is depicted? (Is that an ibis?) Does it all

still thrive around the Nile?