By: Pieter Broucke, Associate Curator of Ancient Art and Professor of History of Art and Architecture

The Middlebury College Museum holds a collection of some thirty Ancient Greek pottery sherds that as small primary sources greatly enhance the teaching and learning of Greek vase painting. The fragments come from a variety of vase shapes, represent a broad range of subject matter, and illustrate several technical aspects.

Some of the sherds are decorated by artists to whom scholars have attributed vases through a process of erudite connoisseurship based on the so-called Morellian Method. Named for the Italian scientist and art critic Giovanni Morelli (1816–1891), this method involves the recognition of stylistic characteristics shared by a group of works of art. Their common details, such as representations of ears, eyes, clavicles, anklebones and the like, to which the artist did not pay much attention and rendered in an almost unconscious manner, can be used to identify them as the work of a known artist. The British archaeologist and art historian John Beazley (1885–1970) applied this method to the field of Ancient Greek vase painting resulting in the chronological classification and the attribution of thousands of vases, fragments, and sherds to individual artists.

Some of these artists are known by name because they signed some of their vases (e.g. Lydos, Psiax, see below). Other artists are named for the potter with whom they worked (e.g. the Antimines Painter, the anonymous painter who worked with Antimines the potter), for a so-called name vase (e.g. Berlin Painter, named for a vase now in Berlin), for a collection (e.g. the Rycroft Painter, named for a British collection), for notable or favorite subjects (e.g. the Painter of the Berlin Dancing Girl or the Theseus Painter, see below), or for a stylistic characteristic (e.g. Elbows Out, the name given to an artist whose figures always have, well, their elbows out!).

Like complete vases, sherds can shed light on broad cultural developments. Presented here are six sherds, arranged in chronological order, that have been attributed to specific hands. In their brief discussion we explore what these sherds tell us about the cultural and historical context that produced them. We will first look at three black-figure sherds, then at three red-figure sherds.

Black-Figure Sherds

Black-figure vase painting developed during the Early Archaic period (c. 600–550 BCE), when vase painters in Athens applied the silhouettes of their subject matter by means of a thin clay slip (which turns black when kiln-fired) to the courser clay surface of the vase (which turns red when fired). Interior details such as eyes and ears were then carefully incised through the slip to expose the clay below.

An early black-figure sherd in Middlebury’s collection shows the right edge and black border of a figural panel and the upper body of a youth, facing left and energetically clapping his hands. From the shape we can deduce that the sherd came from a hydria, a water jar with three handles. The sherd was attributed by Dietrich Von Bothmer (1918–2009), the erstwhile curator of Antiquities at the Metropolitan Museum in New York City, to a vase painter whose name we know because he signed his name on two vases as “ό Λυδός,” (“ho Lydos”), meaning “the Lydian.” This name indicates that he or his father was an immigrant from Lydia, in Asia Minor (the west coast of modern-day Turkey). From his style, however, it is clear that he trained in Athens where he subsequently established himself as a prominent and influential artist. This is indicative of Athens’ artistic draw during the Early Archaic Period, attracting artists from near and far in the Ancient Greek world.

A second black-figure sherd depicts the face of a horse and the head of a youthful attendant with a panel border behind him. The shape and border indicate the sherd comes from an amphora, a two-handled storage jug usually used for wine. The sherd was attributed by Ernst Langlotz (1895–1978), a German scholar, to another artist we know by name because he too signed some of his vases with his name, “Ψίαξ,” “Psiax.” The artist was a vase painter active between c. 525 and 505 BCE, a period of great creativity and innovation. He worked with Andokides, the potter in whose workshop red-figure vase painting was invented around 525 BCE. Psiax himself worked both in the black-figure and in the red-figure technique, as well as in some other more experimental techniques. All of this is indicative of Athens’ innovative climate during the Late Archaic Period, where artists competed against each other and built upon each other’s ideas and work. As such, Early Archaic Athens was not unlike Flanders and Tuscany in the fifteenth century, Paris in the nineteenth century, or New York in the decades right after World War Two.

A third black-figure sherd is the rim of a large skyphos or drinking cup. It depicts Hermes, recognizable by his travel hat and beard, facing Ariadne, in a scene from the stories about Theseus, the hero and mythical king of Athens. Von Bothmer attributed the sherd to the so-called Theseus Painter, an anonymous Late Archaic vase painter whose subject matter nearly always pertains to the Athenian hero. The Theseus Painter continued to work in the the black-figure style long after red-figure had been invented. This is indicative of the artist’s conservative artistic personality.

Red-Figure Sherds

Around 525 BCE the red-figure technique of Ancient Greek vase painting developed. In this technique the thin clay slip was now applied to the background around the silhouettes of the figures. After firing, the reserved figures stood out in bright orange against the dark background. Interior details such as eyes, ears, and musculature were added by applying lines of slip which could be thin, thick, or watered down.

Red-figure vase painting became the dominant technique during the Classical period (480–404 BCE), and saw continued experimentation with composition, perspective, foreshortening, and faces depicted in frontal and three-quarter views. Over time, the painting style became mannerist, emphasizing gesture and pose.

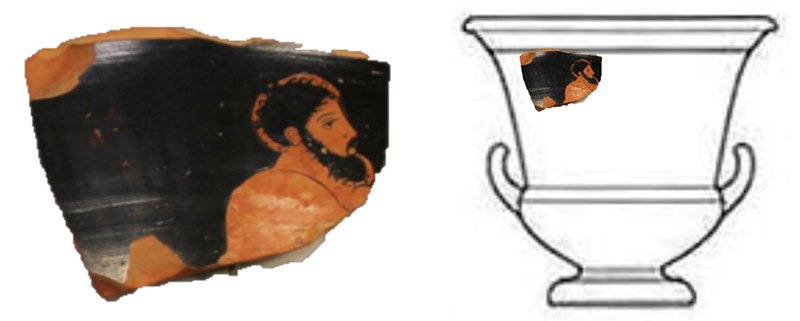

This first red-figure sherd depicts a bearded elder in the High Classical style exemplified by the Parthenon Frieze on the Athenian Acropolis. The sherd was attributed by Von Bothmer to the so-called Painter of the Berlin Dancing Girl after a calyx krater now in Berlin. Active between c. 430 and 410 BCE, the artist is one of the first South Italian red-figure vase painters. From his style, however, it is clear that he trained in Athens and then either returned or migrated to Apulia, modern-day Puglia in southern Italy.

This red-figure shard shows the head and upper body of a woman. The laurel pattern on the projecting surface above her head indicates the sherd belonged to a large Calyx Krater. It may be attributed to the so-called Painter of Athens 1714, a red-figure vase painter active in Apulia between c. 370 and 360 BCE. The edges of the sherd reveal it was made from southern Italian clay that fired a dull tan because of its low iron content. It was then coated with a layer of clay with a higher iron content that, when fired, displays the reddish effect of Athenian pottery. This indicates the high esteem in which Athenian pottery was held well into the fourth century BCE, and the efforts that were made to mimick Athenian vases.

A last red-figure sherd depicts the head of a bearded satyr, his turned-up nose just barely preserved. The laurel leaf pattern above the figure and the shape of the sherd indicate it belonged to a bell krater. The sherd was attributed to the so-called Lecce Painter by Von Bothmer. Named for the many bell kraters by his hand that are now in Lecce, in southern Italy, the anonymous vase painter has a flamboyant artistic style involving the addition of white accents. This sherd is evidence of the late flowering of Greek vase painting that occurred in southern Italy towards the end of the Classical period.

Greek vase painting all but disappeared during the beginning of the Hellenistic period (323–31 BCE), when painted decoration, increasingly rare, became less figurative. Over time, mold-made wares became popular.

The other sherds in the museum’s collection depict a variety of figures (humans, heroes and gods) as well as animals (horses, deer, even a flying bird) in both the black- and red-figure technique. They remain to a large extent unstudied and are unattributed, thus providing research opportunities for students in Classical Studies and Art History. Together with the attributed sherds here discussed, the museum’s collection thus enriches Middlebury’s academic program.

All sherds came to Middlebury from a Roman collection brought to the US in 1961, a private American collection, and the collection of Ernst Langlotz in Bonn, Germany.

This is a great collection of Greek vase fragments. I was pleasantly surprised to see that Middlebury College, like Bowdoin College, is “an acorn in the forest.” They are excellent for teaching.