by Annaliese Terlesky ’23.5, Robert F. Reiff Curatorial Intern

In the Middlebury College Museum of Art’s recent exhibition, Tossed: Art From Discarded, Found, and Repurposed Materials (May 26–December 10, 2023), Duke Riley was one of many featured artists who have used what would usually be considered disposable objects as artistic material. Through the process of discarding, finding, and repurposing these materials, these artists communicate compelling messages that otherwise would not translate if they were to employ only traditional media.

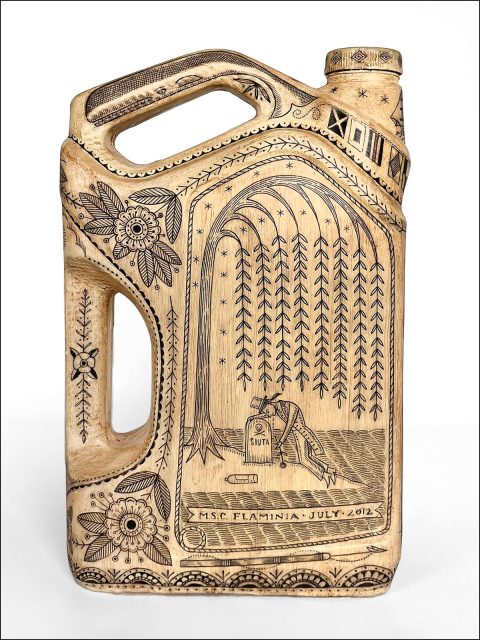

In Riley’s case, an ironic, confrontational use of plastic sits at the heart of his practice in the Poly S. Tyrene Memorial Maritime Museum series one of which, no. 382, was commissioned by Middlebury for its permanent collection. Rethinking and re-presenting scrimshaw—decorated bone and ivory—he replaces the traditional medium with discarded, often plastic household items he has found washed up on New York City’s shoreline.[1] In doing so he references a throughline of environmental, specifically marine, exploitation in the past and present. The elaborately decorated bone and ivory from centuries past was tangible evidence of an industry that nearly depleted whale populations to fulfill industrial demand. Riley’s art modernizes this practice by using the excesses of the plastic industry as his medium to direct attention toward extreme, wasteful production and consumerism that has resulted in oceans brimming with trash.

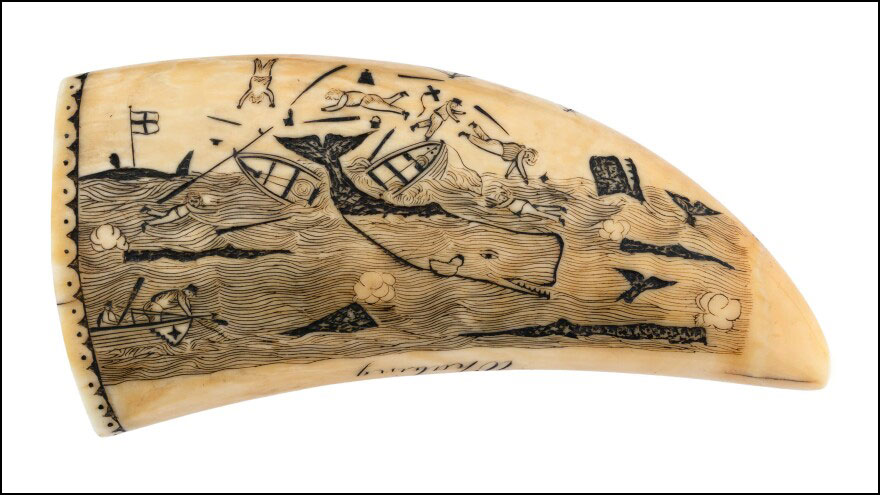

Scrimshaw, the genre of artmaking Riley references, was an “occupational handcraft” or art of whalers that gained popularity during the 1820s.[2] Precursors had appeared earlier, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, in Holland and Germany, but it was only after Americans began whaling in 1712 that sperm-whale bone and ivory became available as materials for scrimshandering, and only after a surplus of whale teeth in the market occurred around 1815, that scrimshaw in its most well-known form began to appear.[3]

Additionally, once the Pacific whaling grounds were opened in the 1790s, voyages were extended, crews were expanded, and, as a result, sailors experienced large windows of leisure time.[4] When they were not hunting, turning whale blubber into oil, or maintaining the vessel, they took up various avocations to occupy themselves: they read, journaled, wrote and performed music, and began to create artwork out of surplus whale bone and ivory. By the 1820s, this art, which came to be known as scrimshaw, was commonplace in the whaling industries of Great Britain and the United States, two of the world’s greatest, and most exploitative, imperial powers at the time.[5]

What emerged as an avocational activity, however, quickly became a complex, visually elaborate artform. Sailors would often use their ordinary knives to carve scenes into available whale teeth and bone, and afterward they would apply lampblack, ink, or “home-brewed” natural dyes to the carved bone, leaving the engraved lines darkened when the pigment was rubbed off.[6] The most frequently depicted scenes involved maritime landscapes of ships at sea, but portraits of powerful individuals within the industry were also common.[7] Scrimshaw art was so widely known in nineteenth-century American culture that it was featured in Herman Melville’s acclaimed novel Moby Dick, in which he described scrimshaw as “the numerous little ingenious contrivances [fishermen] elaborately carve out of the rough material, in their hours of ocean leisure.”[8]

The art form dwindled in production in the late nineteenth century after the United States government introduced kerosene as an alternative for whale oil, the industry of which had killed so many whales that this mode of energy became entirely unsustainable.[9] However, turning to fossil fuels, the nation essentially jumped from one extractive, exploitative process to another, the legacy of which we are facing today with the increasingly evident onslaught of environmental catastrophe related to the planet’s warming climate.

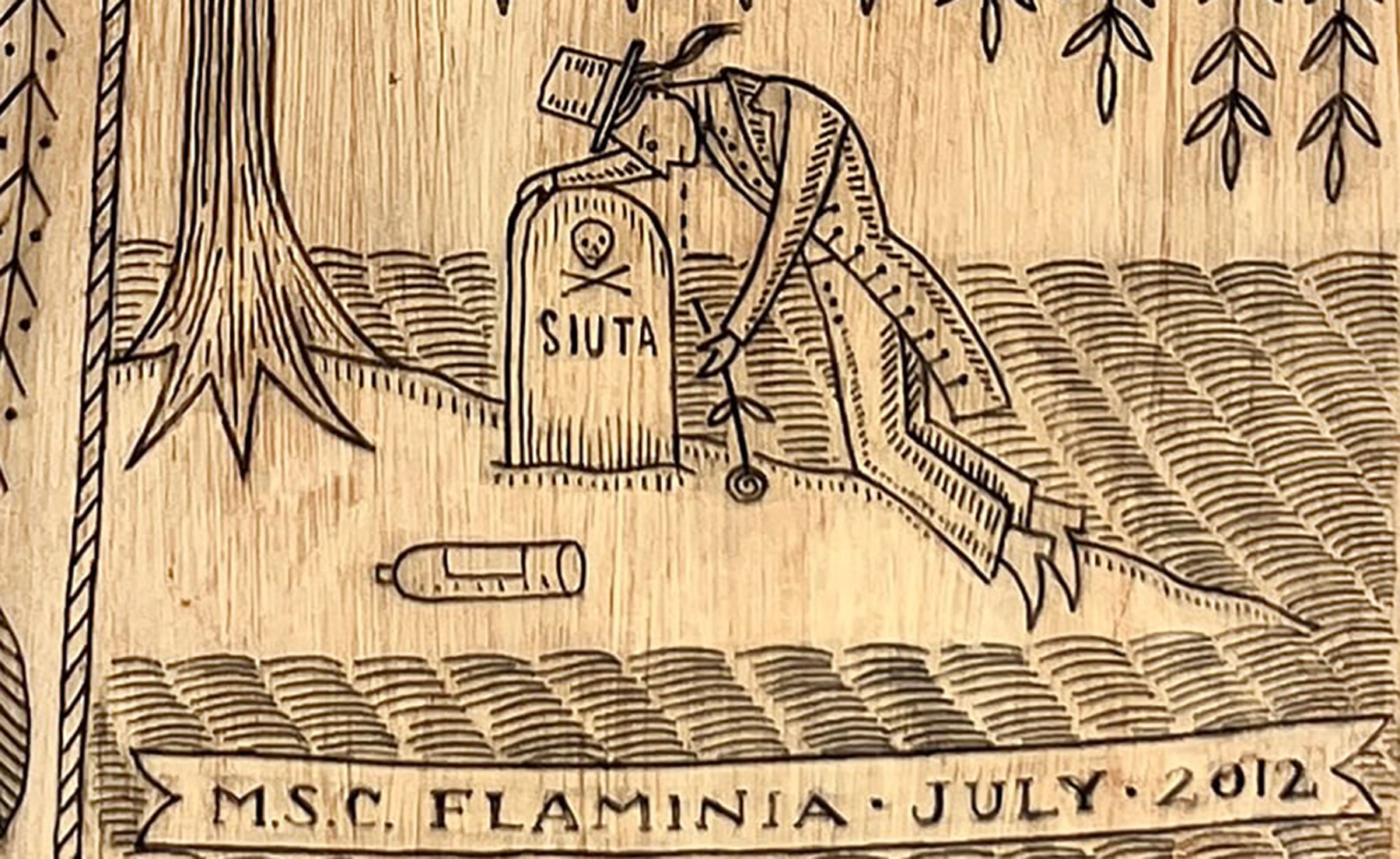

Riley presents contemporary scrimshandering through his Poly S. Tyrene Memorial Maritime Museum series. He gathers household items—anything from detergent bottles to flip flops—and paints them beige to mimic the color of whale bones. Then, in black India ink, he renders contemporary narratives onto the disguised plastic bottles, once colorful to catch the consumer’s eye, and now only distinguishable via shape.[10] No. 382 was once a Shell engine oil container, and upon it Riley has drawn fine botanical designs that mimic those represented in nineteenth-century scrimshaw art, along with a whale in the top handle, and a man crouching over a grave that reads “SIUTA” in the center. A caption written on a banner reads “M.S.C. FLAMINIA JULY 2012,” referencing a container ship of that very name that underwent several explosions during a one-week period that year.[11] In addition to spilling an unknown number of containers onboard into the Atlantic, the disaster killed three sailors, one of whom was Cezary Siuta.[12] By displaying his name on the gravestone over which a wealthy oil barren leans, Riley points fingers at those in power for the deaths of their inferiors, as well as for the devastation they actively reap on oceans via extractive practices and ones that litter the ocean with the very materials he uses.

As scrimshaw art of earlier centuries offers a glimpse into the unique era and culture that produced it, so too does Riley’s new scrimshaw offer its viewers a narrative lens to look at the human-nature—or, more specifically, the human-ocean—relationship in the world today. The very medium of scrimshaw art called attention to the existence of an industry that relentlessly slaughtered sea life to fuel human technological advancement. Today, “unchecked consumption” of the very plastic items Riley disguises has led to oceans lined with shores of trash, the very harvesting site for Riley’s materials. With his practice of engaging what is disposable and has widely been disposed—a practice that extends beyond this scrimshaw series—he hopes to “hold people accountable,” as well as point them to the “little acts that people can take to solve this problem.”[13]

Sources:

“Art and Literature.” New Bedford Whaling Museum.

https://www.whalingmuseum.org/learn/research-topics/whaling-history/art-and-literature/

“Details on the Container Ship MSC Flaminia Accident.” Marine Insight, September 15, 2012.

https://www.marineinsight.com/case-studies/details-on-the-container-ship-msc-flaminia-accident/.

Ebert, Grace. “By Engraving Found Plastic Waste, Duke Riley Links Extractive Practices

Throughout Human History.” Colossal, July 6, 2023. https://www.thisiscolossal.com/2023/07/duke-riley-plastic-scrimshaw/.

Granby, Alan. “The Whaler’s Art: Scrimshaw.” Incollect, last modified July 27, 2022.

https://www.incollect.com/articles/scrimshaw-the-whaler-s-art.

Ryzik, Melena. “Duke Riley: Grand Master Trash.” The New York Times, June 16, 2022.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/16/arts/design/duke-riley-artist-brooklyn-museum-trash.html.

“Sailor Cezary Siuta dies after blast on MSC Flaminia.” BBC News, October 29, 2014.

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-cornwall-29818331.

Wertkin, Gerard, Lee Kogan, and the American Folk Art Museum. Encyclopedia of American

Folk Art. New York: Routledge, 2004.

[1] Melena Ryzik, “Duke Riley: Grand Master Trash,” The New York Times, June 16, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/16/arts/design/duke-riley-artist-brooklyn-museum-trash.html.

[2] Dr. Alan Granby, “The Whaler’s Art: Scrimshaw,” Incollect, last modified July 27, 2022, https://www.incollect.com/articles/scrimshaw-the-whaler-s-art.

[3] Gerard Wertkin, Lee Kogan, and the American Folk Art Museum, Encyclopedia of American Folk Art (New York: Routledge, 2004), 467.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid; and “Art and Literature,” New Bedford Whaling Museum, https://www.whalingmuseum.org/learn/research-topics/whaling-history/art-and-literature/.

[6] Granby

[7] Ryzik

[8] Wertkin et al.

[9] Grace Ebert, “By Engraving Found Plastic Waste, Duke Riley Links Extractive Practices Throughout Human History,” Colossal, July 6, 2023, https://www.thisiscolossal.com/2023/07/duke-riley-plastic-scrimshaw/.

[10] Ryzik

[11] “Details on the Container Ship MSC Flaminia Accident,” Marine Insight, September 15, 2012, https://www.marineinsight.com/case-studies/details-on-the-container-ship-msc-flaminia-accident/.

[12] “Sailor Cezary Siuta dies after blast on MSC Flaminia,” BBC News, October 29, 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-cornwall-29818331.

[13] Ryzik.