By: Pieter Broucke, Associate Curator of Ancient Art and Professor of History of Art and Architecture

A Quixotic Personality

Born in Venice in 1720, Giovanni Battista Piranesi was an archaeologist, architect, and artist active in the second half of the eighteenth century in Rome where intellectual circles actively disputed the “true fountainhead” of Western civilization, whether ancient Rome or ancient Greece. Piranesi championed the ancient Roman side.

That debate led Piranesi to get creative with the archaeological evidence that he marshalled in support of ancient Rome’s greatness, and this cinerary urn is a telltale example of that: he augmented the marble cinerary urn with a modified lid from a small ancient funerary altar, had a modern inscription carved into the urn’s blank panel “after the antique,” and provided the whole with a modern marble base of his own design.

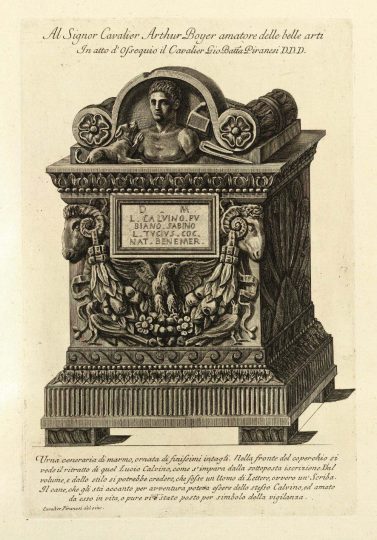

A prolific artist, Piranesi subsequently made an etching of the resulting diachronic pastiche and included it in the second of two folio volumes dedicated to ancient Roman decorative arts, published for the first time just prior to his death in 1778.

The composite ancient Roman cinerary urn and its accompanying print, both recently acquired by the museum, bear testimony to the eighteenth-century reception of antiquities as well as to Piranesi’s quixotic artistic personality.

The Urn

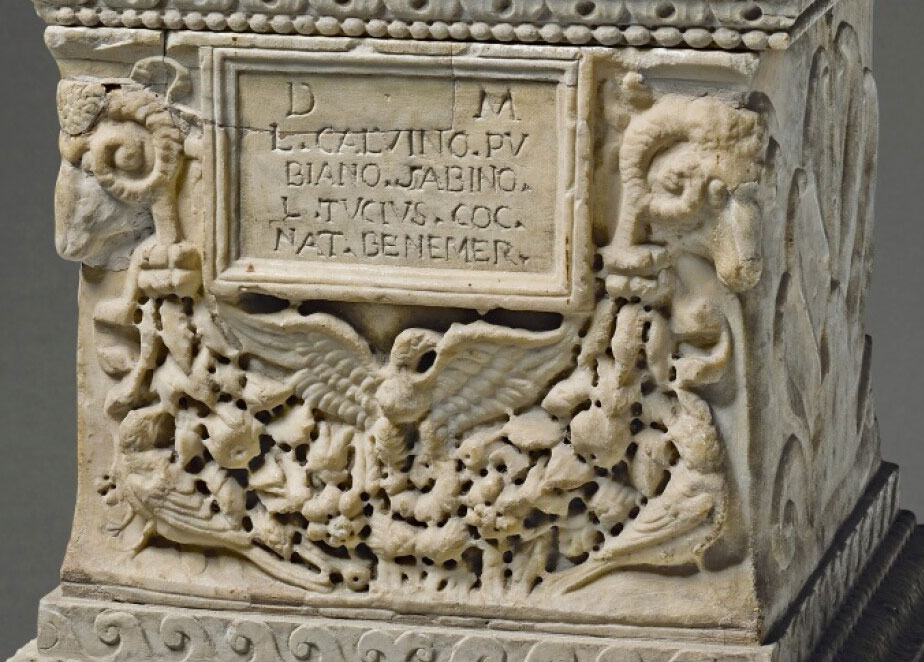

The cinerary urn has been recombined from various parts ancient and modern. Piranesi had the top of a small ancient funerary altar modified to fit the urn beneath it. Carved to look like a miniature tiled roof, the front features a half-circular imago clipeata (essentially, a bust) of a young boy with, on his right, a small dog longingly reaching out to its deceased master. On his left is a satchel and, perhaps, a wax tablet with its leather cover, signaling the boy’s scholarly virtues. On each side are Ionic scrolls with floral finials inspired by Hellenistic motifs. Around its lower edge runs a molding carved in modern times and consisting of a row of lotus leaves above a row of beads.

The style of the boy’s head is Julio-Claudian (the hair resembles that of the young Nero). Allowing for a gap between when imperial portraiture ideas are created and when they find acceptance in works of art made for the Roman middle-classes and entrepreneurial freedmen, it is likely that the lid dates to the late first century CE, probably to the early Flavian Dynasty.

The ancient cinerary urn beneath features rams’ heads on the front corners. The front is decorated with a festoon with, centered above it, an eagle with its wings spread, and on the two corners below it, two birds. The overall proportions, the drill work on the front of the urn, and the Hellenizing palmettes on the flanks recall cinerary boxes from the second century CE. While this constitutes standard iconography, it is most definitely not usually associated with a child. It is likely this was a workshop piece, generic in its iconography, and with a text panel left blank.

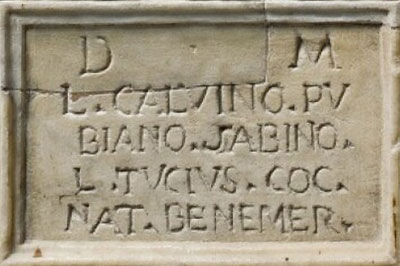

The inscription is modern and is crudely, even naively, carved. It follows standard ancient abbreviations and is worded in the first person—a father dedicating the urn to his deceased son: “D[is] M[anibus]/L[ucio] Calvino Pu-/biano Sabino/L[ucius] Tucius Coc[ceius]/Nat[o] benemer[enti]” (“To the Spirits of the Departed. Lucius Tucius Cocceius [made this] for Lucius Calvinus Pubianus Sabinus, his well-deserving son;” See CIL, VI, Part V [dealing with forged inscriptions], no. 3508). By means of the inscription Piranesi aimed to link the urn to the image of the boy in the re-carved funerary altar top above it.

The modern socle is of Piranesi’s own design, conceived in a decidedly neoclassical style. Unlike the bead molding, the wave motif is not usually seen in Roman sculpture. The leaf motif under it makes use of a finer drill than was used on the ancient cinerary box. Finally, the base with its vertical flutes anticipates the restrained forms of French imperial neoclassicism under Napoleon.

The sculpture was in the collection of the Marquis de Pennautier, France, by 1883. It was probably acquired in Rome by Vicomte Jacques Amable Gilbert de Saint Pardoux on his Grand Tour in 1779, for the Château de Pennautier near Carcassonne in the Languedoc.

The Etching

Piranesi’s etching shows his sculptural pastiche in a so-called “cavalier perspective” in which the face of the object is depicted frontally with the top and lateral faces foreshortened and receding at a 45-degree angle. Careful shading further enhances the 3D illusion of an object represented on a 2D surface.

The print shares a sheet with Piranesi’s print of a Sede Curule (not shown here), an ancient Roman chair reserved for dignitaries, also fancifully reconstructed by the artist. The sheet on which both images were printed was cut from a second volume of Piranesi’s monumental publication of ancient Roman decorative arts, Vasi, candelabri, cippi, sarcofagi, tripodi, lucerne ed ornamenti antichi, first published in Rome in 1778.

The print’s wove paper is devoid of a watermark, suggesting the publication to which this page belonged was a fairly rare edition of Piranesi’s publication by Firmin Didot in the 1830s. It was printed in Paris, where Francesco Piranesi, the artist’s oldest son and oftentimes collaborator, had taken his father’s plates in 1799.

Thank you for your inquiry. Piranesi actually “made” several of these. Yet unlike his prints (made during his lifetime and posthumously in Rome and then Paris, where his son Francesco took the plates after his father’s death), these sculptural pastiches are each unique. As such, it is truly wonderful for Middlebury to have this piece available for its students and faculty.

Thank you for your inquiry. Piranesi made several of these. His motivation was in part showcasing the greatness of the Romans and in part commercial. As a dealer in antiquities, he obviously wanted objects to be complete. If they were not complete, well then he would complete them himself! As such, the archaeological “pastiche” is very much of its time.

Did Piranesi make many of these or was this the only one of “constructed past?”