By: Pieter Broucke, Associate Curator of Ancient Art and Professor of History of Art and Architecture

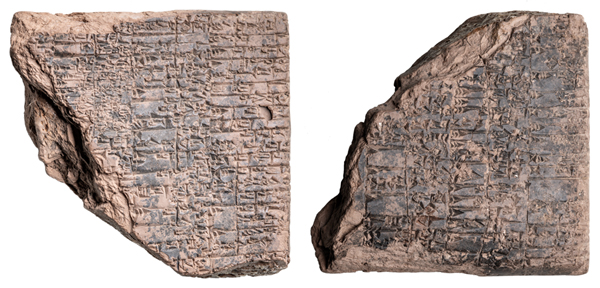

In the fall of 1996, the Middlebury College Museum of Art received a gift from John Paul Wallach, Middlebury alumnus from the class of 1964, and his wife Janet Wallach. It was a fragment of a terracotta tablet with cuneiform inscriptions that had been in the US for nearly a century. We immediately put it on view near other ancient Near-Eastern art including Sumerian beads, a survey of Mesopotamian cylinder and stamp seals, a funerary portrait from Palmyra, and Middlebury’s magnificent Assyrian relief. Realizing it was the corner of a larger tablet, the fragment was installed on a mount that approximated the size of the complete tablet.

Cuneiform, the earliest known writing system, was developed around 3000 BCE in Mesopotamia, the land along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, in modern-day Iraq. Using the tip of a reed stylus, scribes marked damp clay tablets with cuneiform (Latin for “wedge-shaped”) strokes that make up the signs. Originally pictograms, these could represent numbers, objects, concepts, words, and the sounds of words. Cuneiform writing was employed to record a variety of languages: Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, and Hittite among them. Its use lasted into the first century CE.

While visiting Middlebury in 2005 Irving Finkel (check him out on YouTube, he’s somewhat of a star), the Assistant Keeper of Ancient Mesopotamian Script, Languages, and Cultures in the Department of the Middle East at the British Museum, London, and one of the leading specialists on cuneiform inscriptions, examined the fragment and provided important additional information. The tablet is written in Sumerian and dates to the Neo-Sumerian period, when the kings of Ur ruled Mesopotamia. During this time of great prosperity, monuments such as the Great Ziggurat of Ur were constructed and parts of the Epic of Gilgamesh were first composed and written down.

The Middlebury fragment, however, does not pertain to Mesopotamian literature but bears witness to the bureaucratic organization of the centralized Neo-Sumerian state. According to Dr. Finkel, it was part of a large tablet on which entries on smaller tablets were copied at the end of each month. That clay tablet was then fired and formed a permanent record kept for archival purposes. The preserved entries include names and measurements pertaining to officials who dispersed wages to workmen, many of them working in fields growing barley or digging irrigation channels. It also lists subsistence fields (called shuku) that were issued to individuals who were clients of a temple in return for livestock and barley.

Covered with inscriptions on both sides, the fragment constitutes the upper right-hand side of the front (the side with the flat surface) and the lower right-hand side of the back (the side with the slightly domed surface). Each side probably had ten columns of text, written from left to right and top to bottom. An inscription with the day, month, and year the tablet was created was usually included on the lower left-hand edge of the back of the tablet and so is not preserved here. Halfway down the fragment’s front, a fingerprint has been fired into the surface. It bears witness, in a surprisingly visceral and tangible way, to the Ancient Mesopotamian scribe who, some four thousand years ago, created this tablet.

If you’re hooked on cuneiform, you might enjoy exploring the microsite dedicated to our Assyrian relief on our VIRAL (Virtual Inspiration, Research, And Learning) project hub.

Pingback: DaDepo project – DaDepo