Henry Sheldon’s 23rd spindle procured for his Windsor chair allegedly comes from the William Penn house in Pennsylvania. William Penn is an interesting character in American history and had a huge impact on the state of Pennsylvania specifically, which is probably why Sheldon wanted to procure a relic from his home. Though the significance of the spindle lies in William Penn’s legacy, the reality is more complicated.[1]

Born into a high class family in England, Penn was groomed by his father to take his place as the head of the family.[2] After attending Christ Church College in Oxford and having a tough experience there, Penn questioned his religion and eventually converted to become a Quaker.[3] This led to imprisonment along with nineteen other Quakers for attending a meeting in 1667.[4] After being released from prison, Penn was then kicked out of his father’s house before being imprisoned a second time in the Tower of London for denouncing the Holy Trinity.[5] It was his third imprisonment that made him the both polarizing and national figure that he is recognized as today. After multiple more arrests for his Quakerism, Penn concluded that there was little hope for religious tolerance in England and began to play with the idea of sailing for America.

He received land from the crown as a settlement for debts they owed his father and sailed for America in August of 1682.[6] Upon arrival, Penn successfully founded Pennsylvania. The state was focused on creating a highly tolerant and accepting culture that was lacking from his life in England. Most of the significance of the relic lies in William Penn’s historical presence in American history. At the time when Sheldon acquired the relic, the house it was procured from was thought to have been the primary residence of William Penn, built by Penn in 1682 and given to his daughter Letitia in 1701. Originally located in the “Old City” of Philadelphia (on Letitia Street between Market and Chestnut streets), the house was moved in 1883 to the Fairmount Park neighborhood for preservation. By the 1930s, subsequent research indicated the house had been misidentified and had no connection to Penn, but when Sheldon bought the wood, he believed it to be legitimate.[7]

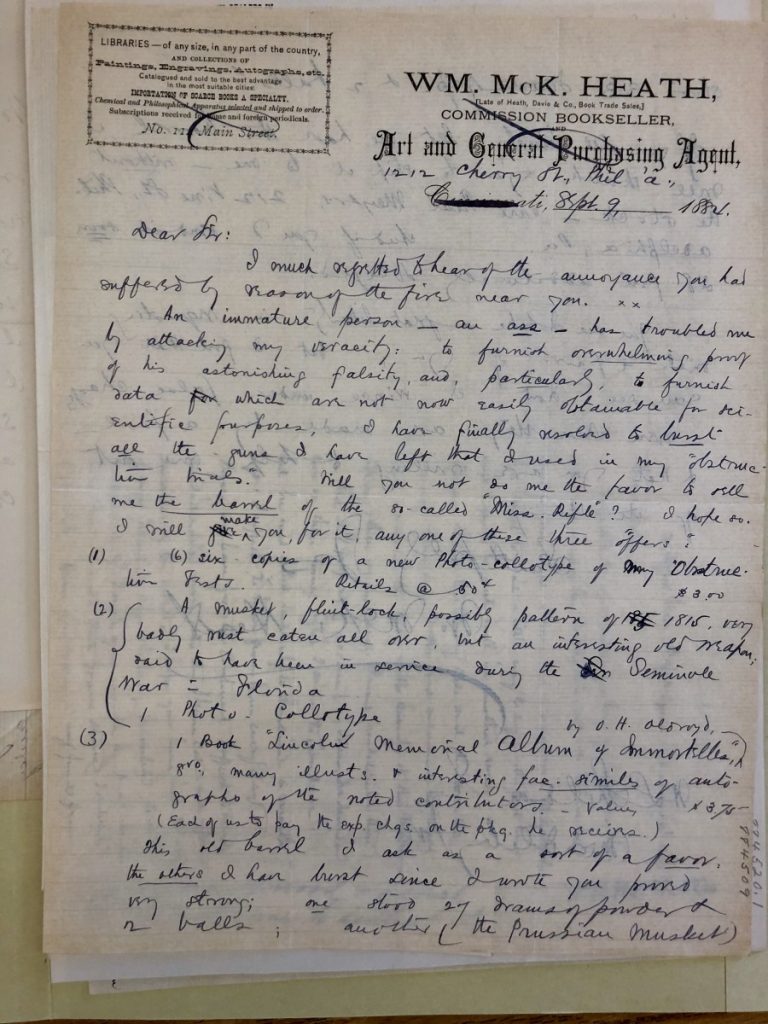

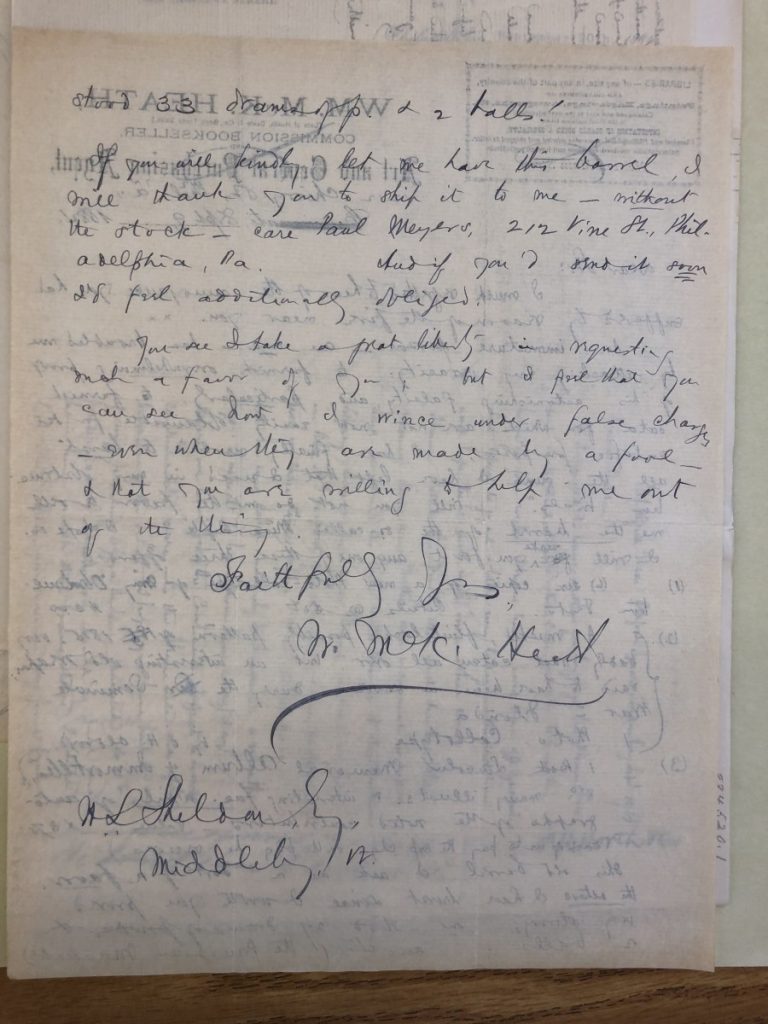

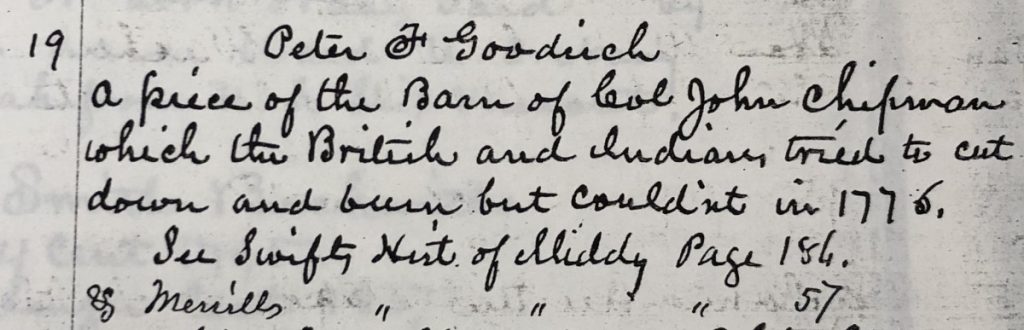

Sheldon purchased the relic from William McKay Heath around the time of the house’s move to Fairmount Park.[8] Not much information has been historically documented about William Heath as a person or what his life story is. Sheldon does not seem to have known him very well, recording his name incorrectly in the Memorial Chair notebook as “McKay Keith.” What we do know is that he corresponded with Henry Sheldon regarding the potential to trade for the barrel of a specific rifle.[9] According to the letterhead he used in this correspondence, Heath was a rare book and art dealer.[10] Being located in Philadelphia and being employed in such a profession explains his access to the three relics he sold to Sheldon.

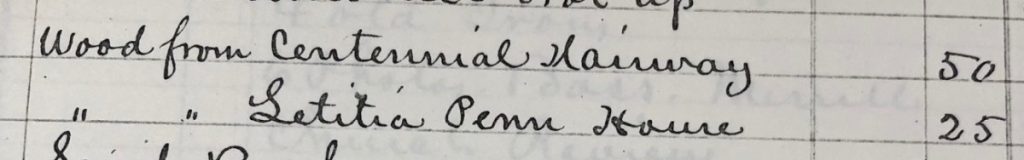

Along with a piece of wood from Letitia Penn’s house, Sheldon also purchased a relic from the the Centennial Building in Philadelphia.[11] Sheldon likely included these three relics because of their patriotic historical relevance even though the three had little to do with Vermont specifically.

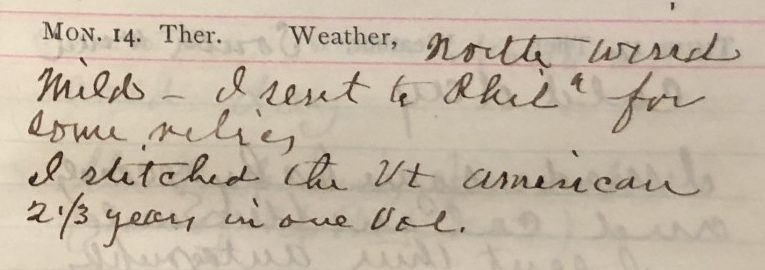

Sheldon had written to Heath in pursuit of Philadelphia materials in mid-January of 1884, noting in his diary that he had “sent to Phila for some relics.”

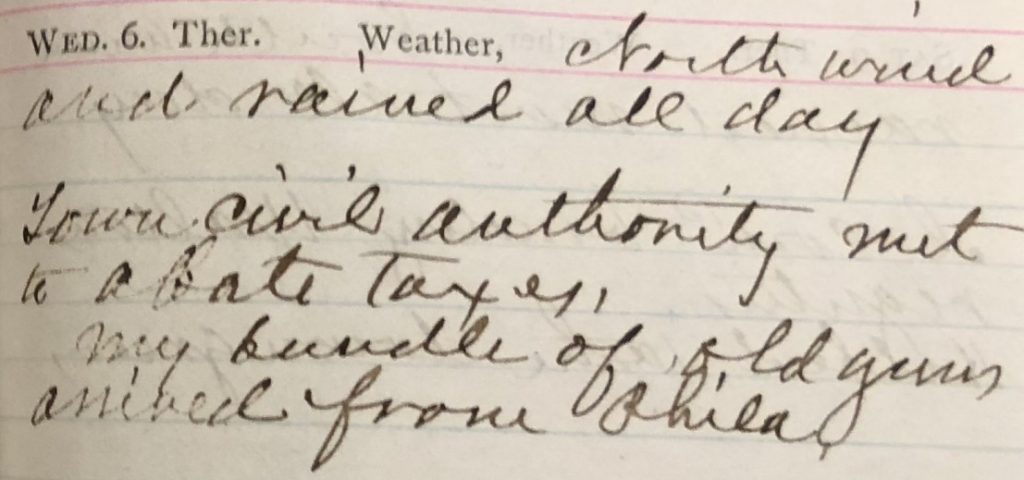

Sheldon seems to have prized these objects, referring to them in a diary entry as his “bundle of old gems from Philadelphia” when they arrived a few weeks later, in early February of 1884.

Of all of the relics featured in the chair, the three relics from Philadelphia are incredibly significant to American history in a greater context. On top of that, they give the chair a more national dimension that would not be there to the extent that it is with them. Unfortunately, it seems as though Sheldon was mislead in believing that the relic actually came from William Penn’s house as aforementioned. The Letitia Penn House actually is not believed to have been built until between 1703-1715, a full 20-30 years after Penn sailed for present-day Pennsylvania.[12] Though this takes away from the relic’s larger significance, it also adds a unique dimension. Relics have been faked and falsely procured for centuries, and this is an example of Sheldon mistaking his relic for one of more significance.

-Grayson W. Ahl ‘19.5

Footnotes

[1] Henry Sheldon, “Acquisition Leger,” Sheldon Museum Archive.

[2] Andrew R. Murphy, “From practice to theory to practice: William Penn from prison to the founding of Pennsylvania,” History of European Ideas 43:4 (2017): 317-330.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Fiske Kimball, “The Letitia Street House,” Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum vol. 27, no. 149 (May, 1932): 147.

[8] Letter from William McKay Heath to Henry Sheldon, 9 September 1884. Letter 884509, Sheldon Museum Archive.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Kimball, 149.

A letter from William McKay Heath to Henry Sheldon requesting the barrel of the “miss. rifle” in return for his choice of three options outlined by Heath. – September 9th, 1884, letter 884509. Henry Sheldon Archive.

Works Cited

Kimball, Fiske, “The Letitia Street House,” Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum 27:149 (May, 1932): 147-152.

Murphy, Andrew R., “From practice to theory to practice: William Penn from prison to the founding of Pennsylvania,” History of European Ideas 43:4 (2017): 317-330.

Sheldon, Henry, “Acquisition Leger,” Sheldon Museum Archive.

“Letter from William McKay Heath to Henry Sheldon,” September, 9th 1884. Letter 884509, Sheldon Museum Archive.

Ullman Manufacturing Co, William Penn House, Digital Public Library of America.

You must be logged in to post a comment.