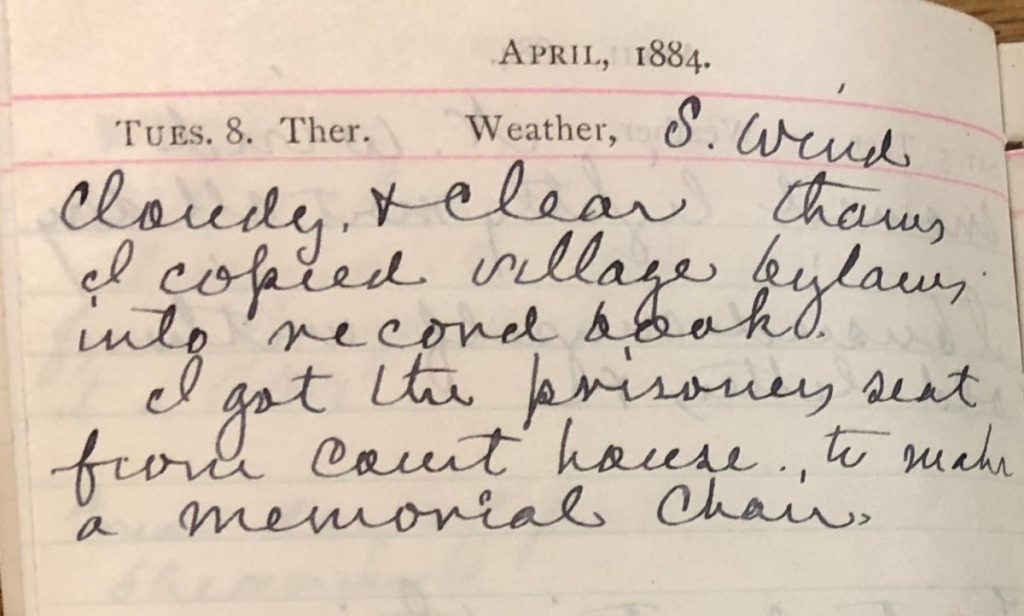

Henry Sheldon hatched plans to build what he called a “Memorial Chair” in April of 1884, when he removed the “prisoner’s seat” from the Middlebury courthouse, then scheduled for demolition. Although he had been assembling a collection of books, newspapers, historical artifacts, and other “relics” for a museum during the course of the 1880s, this April 8, 1884 diary entry is believed to be the first recorded mention of a possible Memorial Chair.

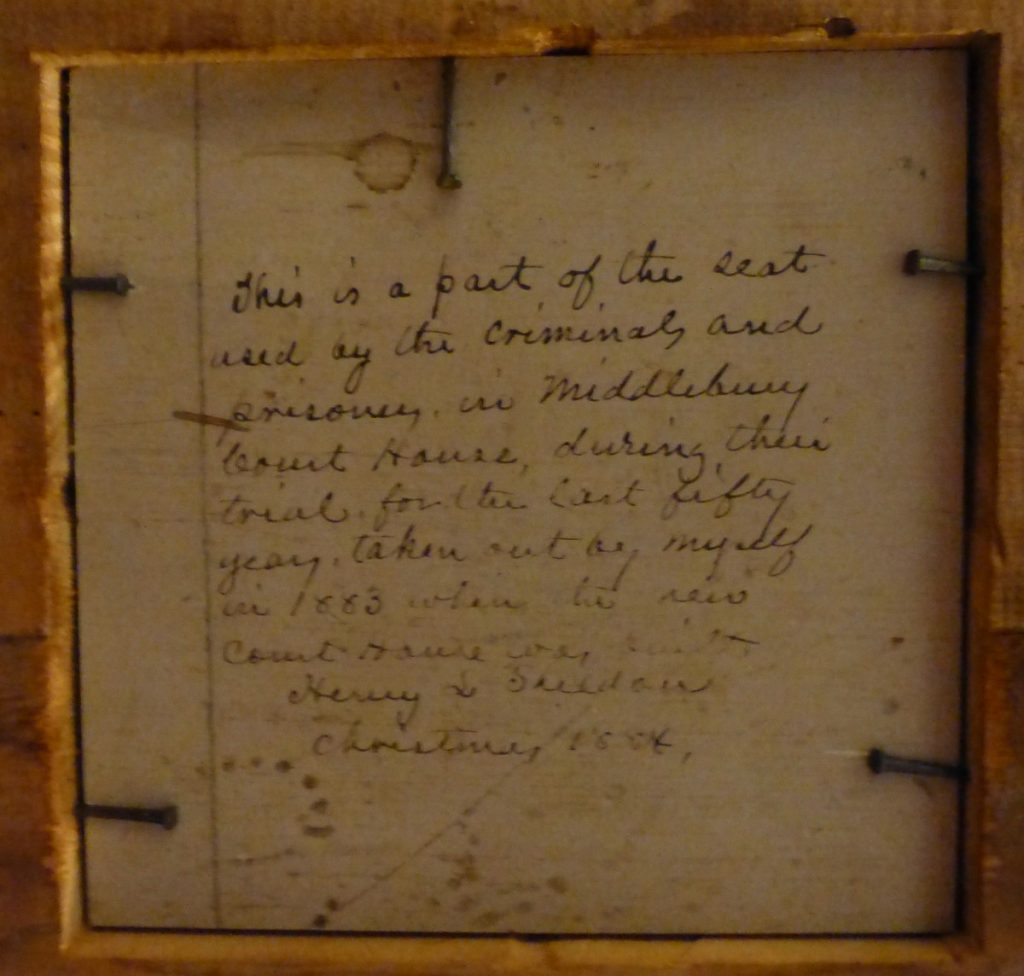

This suggests that it was the seat that inspired the chair. We can imagine a mirthful Henry Sheldon designing an eclectic chair that included various elements of historical significance… only to inform visitors that they were sitting in what had been the defendant’s bench of the local courthouse. Or we might consider a somber and devout Henry Sheldon, who considered all of us to be on trial, subject to God’s judgment. When Sheldon finally inserted the seat into the chair, on Christmas of 1884, he wrote a label indicating the history of the seat as the site where “criminals and prisoners” sat “during their trials,” suggesting a dim view of those who had previously occupied the seat.

Over the summer and fall of 1884, Sheldon assembled a wide variety of wood samples, or “relics,” occasionally noting in his accession ledger or diary that he intended these historic fragments for the “memorial chair.” He assiduously worked on the chair in the last weeks of December 1884, noting in several diary entries that he “had some rounds turned for memorial chair,” applying shellac and varnish to these “rounds,” or spindles, and painting the body of the chair on the last days of the year. His ledger of expenses indicates he paid $1.50 for the “rounds” to be turned, although it doesn’t record who might have performed the work.

The end of the year was a contemplative period for Sheldon, a time of taking stock. As he noted in his diary on the last day of 1884, ” … I painted Memo. chair. This day closes the year 1884, which has closed the lives of my brother Homer, my cousin Martin G. Everts, and my friend Daniel L. Wells, all intimate friends together. My only remaining brother Horace is at the homested [sic] in Salisbury… My health is good except the infirmity of deafness which is gradually tightening its already firm grip, with no hope of relief. All my spare time the past year has been devoted to the interests of the Museum and am now 6 months behind in my labor.” Work on the relic chair was bound up with these contemplations of mortality and the preservation of memory.

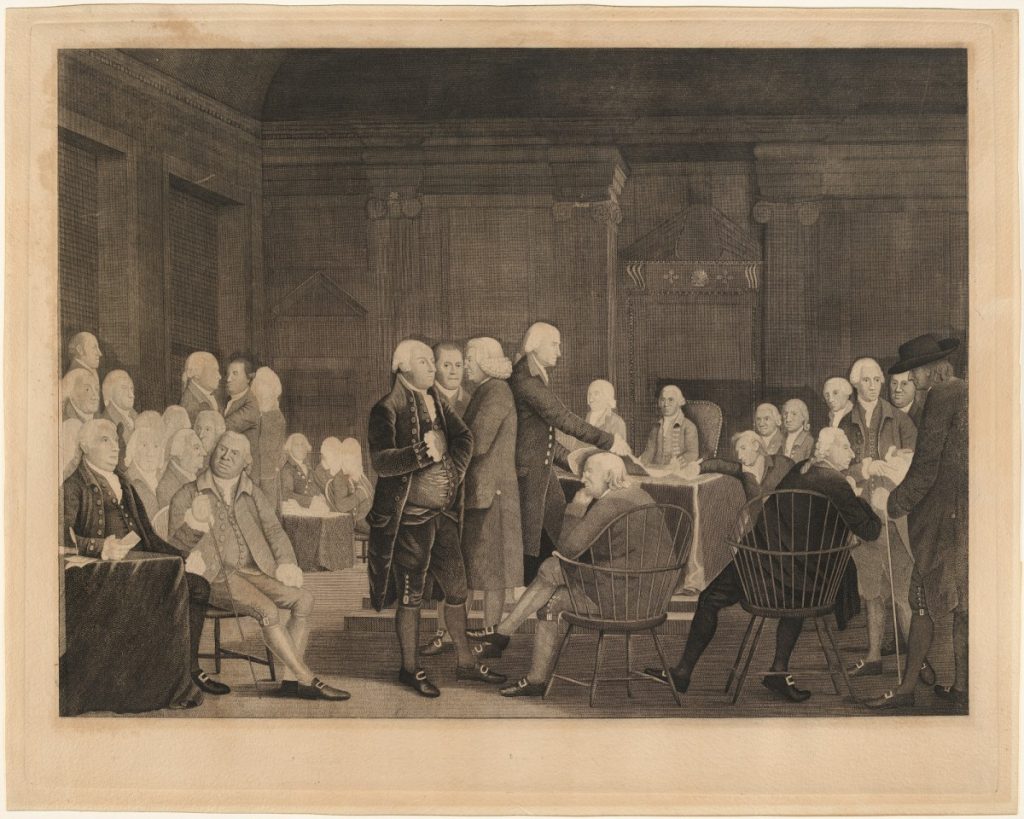

The form of the chair is an eclectic Windsor style: a chair whose back and sides consist of multiple turned spindles that are attached to a solid seat; its straight legs splay outward, and its back reclines slightly. Yet Sheldon’s chair includes two additional rows of spindles and rails, the topmost forming a “comb” back. Windsor chairs were famously used by the authors of both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, and by the late nineteenth century, many people saw the style as quintessentially “American.”

These unupholstered chairs are lightweight and easily portable, fostering mobility and democratic relationships. Windsor chairs are often constructed of many different types of wood, painted to create a uniform appearance; as scholar Jay Fliegelman has suggested, “Like the Continental Congress, which sat on them, the chair was a material culture version of e pluribus unum, it was a whole not only greater than the sum of its parts but one whose heterogeneous materials and connections (like spindles driven deep into the seat rather than attached to it) could often no longer be discerned in that whole.”[1]

Yet Sheldon’s chair celebrates its diverse variety of woods. Although the body of the chair (seat, rails, legs, stretchers) is painted a uniform light blue-gray, the spindles themselves are merely given a light coat of shellac or varnish, proudly displaying their variations and drawing viewers’ attention to the multiplicity of sources, sparking their curiosity about these relics and sites of origin.

– Ellery Foutch, Assistant Professor

Select the “Spindles” tab above to read more about the various sites and sources Sheldon incorporated into his chair, or click on the links below.

Upper row, L-R:

- William Alden House

- John Chipman Barn

- Middlebury Old College

- Middlebury Congregational Church

- Ep. Miller House

Bottom row, L-R:

- Old Ironsides

- USS Vermont

- USS Congress

- Daniel Foot’s barn

- Robert Torrance’s house

- Middlebury Block house

- Holland Weeks’s house

- Moses Sheldon’s house

- Samuel Sheldon’s barn

- Andy Johnson’s Tailor shop

- Middlebury Episcopal Church

- Daniel Foot’s Chest

- Benson Whipping Post

- Neshobe Island

- California Redwood

- Charter Oak

- Centennial Building

- William Penn House

- Declaration House

Seat:

[1]. Jay Fliegelman, Declaring Independence: Jefferson, Natural Language, and the Culture of Performance (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1993), 71-2.

You must be logged in to post a comment.