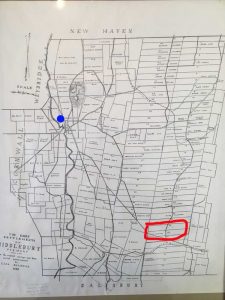

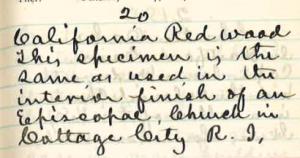

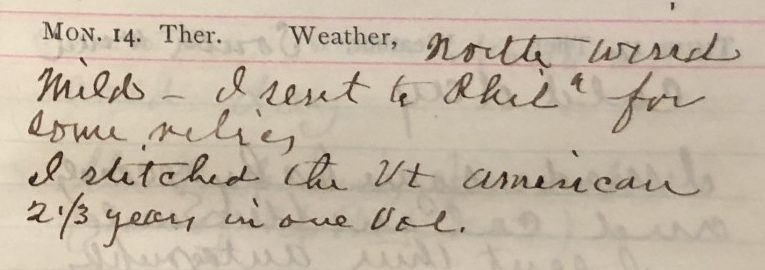

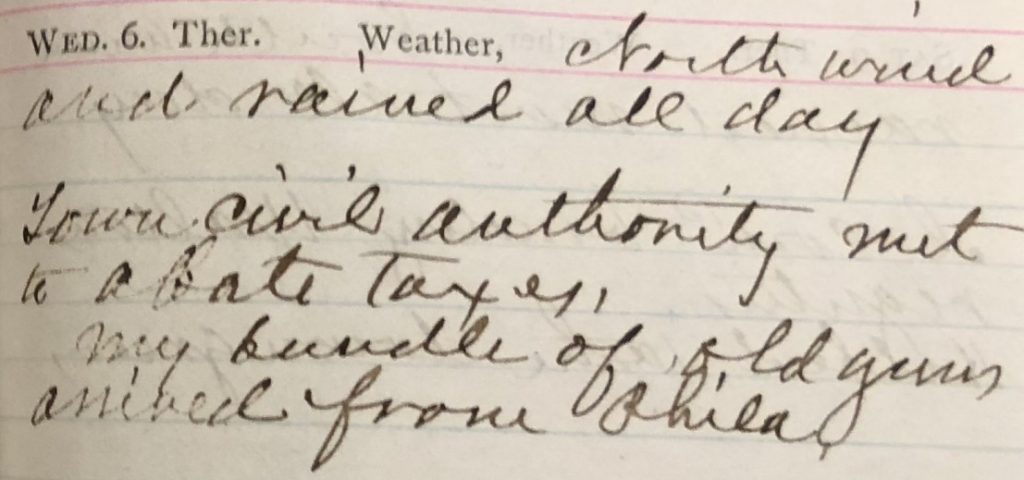

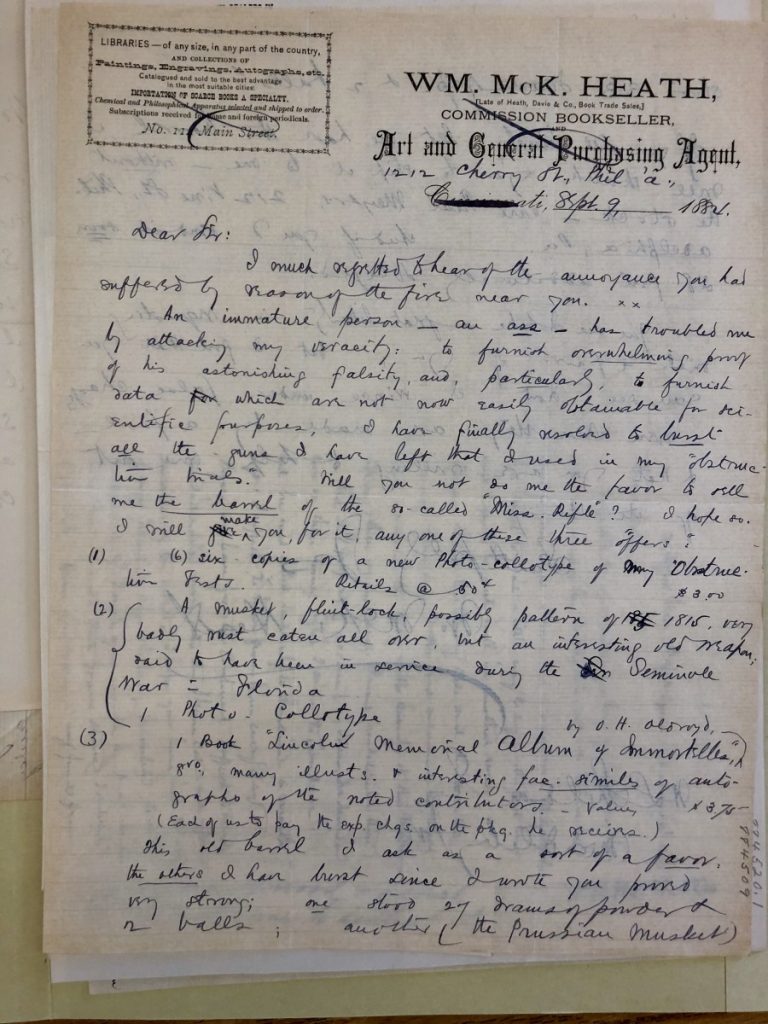

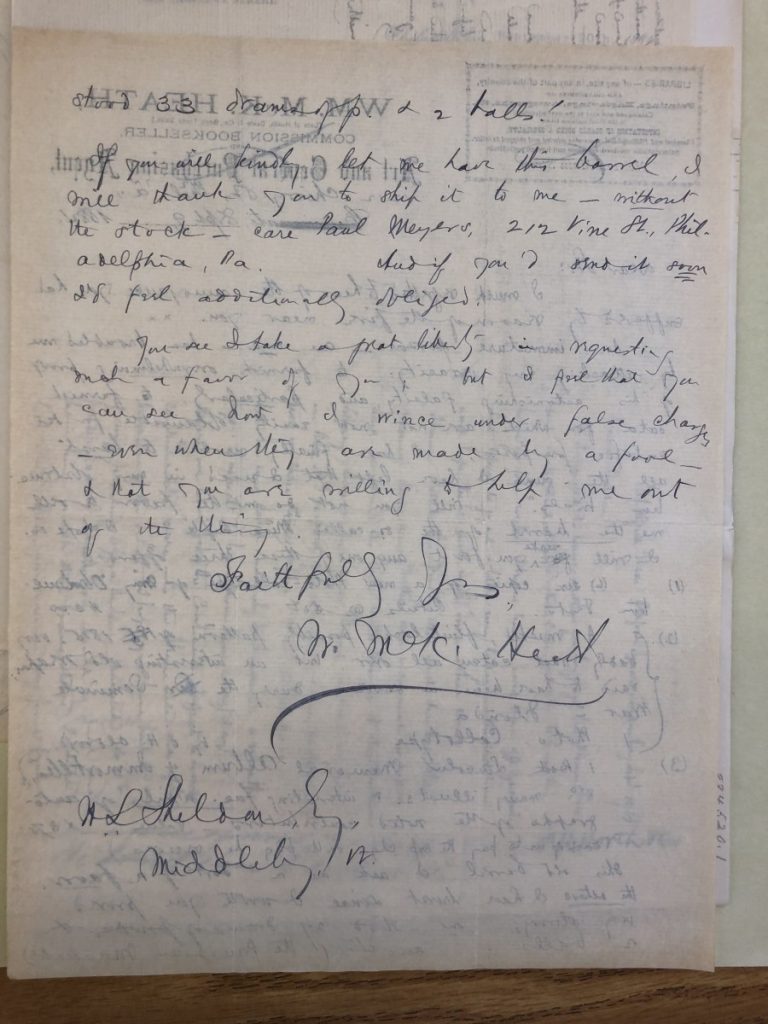

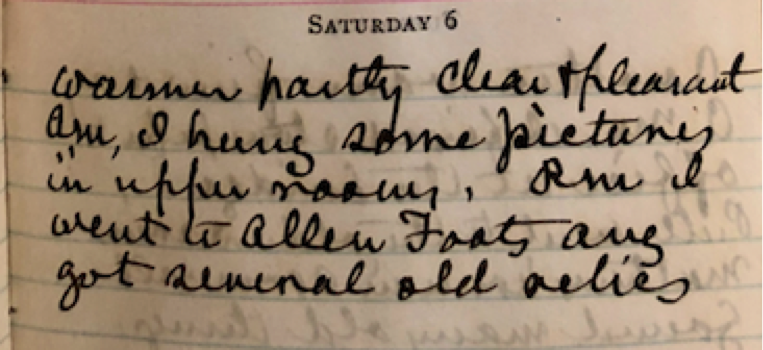

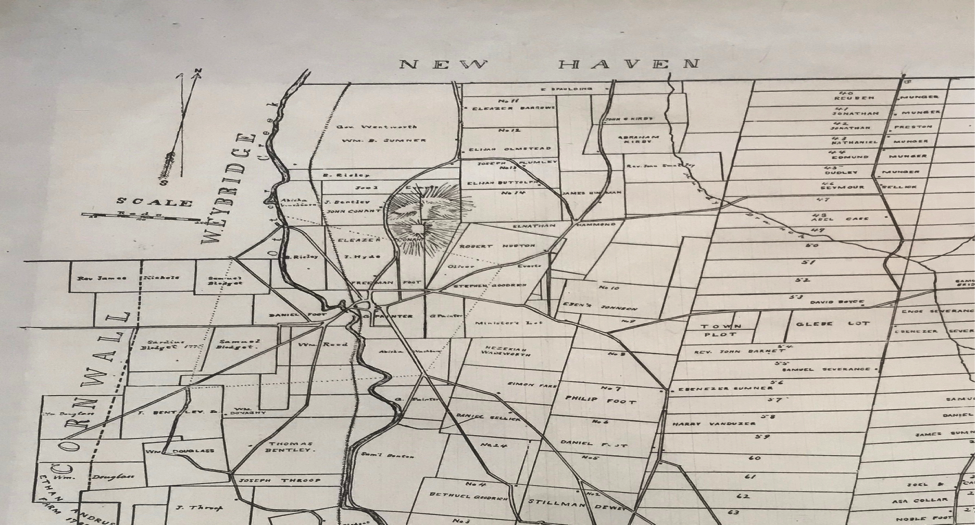

In 1883, Henry Sheldon left his home in downtown Middlebury and traveled approximately five miles southeast along Route 7 to retrieve a sample of wood from the first brick house built in Middlebury. (1) The house, built on lot 33 in present-day East Middlebury(2) was constructed by Robert Torrance in 1774 (3). According to Torrance’s daughter, Olive, Robert Torrance emigrated from Ireland to Woodsbury, Connecticut in 1754, at the age of eighteen. He arrived in Middlebury with other original settlers in 1774, descended Otter Creek on a raft, and purchased lot 33 from a man named Joseph Hyde, along with lot 32.(4) Soon thereafter, Torrance built a log cabin on the land, before building the brick house later that year.(5) Torrance served on Middlebury’s grand jury in its early days alongside a fellow resident by the name of Abraham Kirby.(6)

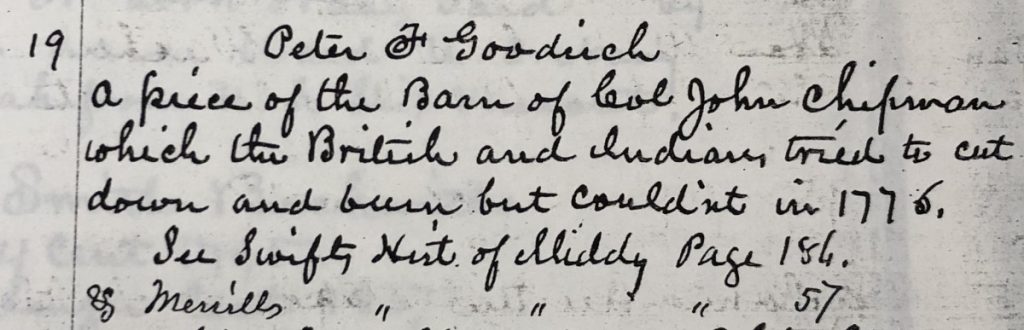

There are several reasons why Henry Sheldon may have regarded a scrap of wood from Robert Torrance’s house as relic-worthy. While Robert Torrance himself was not as significant a figure in early Middlebury as John Chipman, for example, his house was notable for several reasons. First, as mentioned previously, it was the first brick house to be built in Middlebury. Eighteenth-century Vermont was virtually inhospitable for white settlers due to harsh winters and the threat of attacks by the Abenaki Tribe. Most settlers built wood houses, but Robert Torrance’s decision to construct a sturdier brick house would have signified an intention to remain in Middlebury despite the potential complications associated with doing so. Torrance was one of the first permanent residents of Middlebury (others, such as Joseph Hyde had lived in Middlebury temporarily but could not brave the winter in its entirety),(7) and the presence of his brick house would have attracted other settlers to the town. Second, Torrance’s house was one of only four buildings to survive the Revolutionary War after British troops invaded and sacked the town, forcing all residents to flee. The other buildings to survive were Joshua Hyde and Bill Thayer’s houses, which like Torrance’s, were built in East Middlebury, along with a barn built by John Chipman which could not be burnt on account of the wood being wet. (8) Third, the house functioned as one of the first schoolhouses in Middlebury, with Robert Torrance’s daughter, Olive, serving as one of the teachers. (11) It is possible that Henry Sheldon himself was schooled in the house during his early years.

From the significance of Robert Torrance’s house we can deduce that Henry Sheldon’s definition of what constitutes a “relic” encompasses many factors. Included in his chair are relics notable for their national historical significance (USS Constitution, Declaration House, Charter Oak, Andrew Johnson’s Tailor Shop, etc.), or association with a prominent member of the town of Middlebury (Moses Sheldon’s house, Samuel Sheldon’s barn). Robert Torrance’s house seems unique in its “relic-ness” in that its significance isn’t based on its association with a person or event, but rather for its existence: the simple fact that it was the first brick structure to be built in Middlebury, signifying the growth of the town.

Robert Torrance lived on lot 33 in the brick house he had constructed in 1774 until his death in 1816. (10). His family continued to live in the house until its destruction around the time Henry Sheldon procured his wooden specimen in 1883. Although relatively little is known about his life, Robert Torrance almost certainly played an integral role in the early development of the town of Middlebury.

-Noah Fine ’20

Footnotes:

1.Henry Sheldon Papers vol. 19, Collections of Henry Sheldon Museum of Vermont History, Middlebury, Vermont

2. Ezra Brainerd, “The Early Settlements of Middlebury, Vermont” [Map], 1886. Collections of Henry Sheldon Museum of Vermont History, Middlebury, Vermont.

3.Samuel Swift, History of the Town of Middlebury in the Town of Addison, Vermont, a Statistical and Historical Account of the County (Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle Company , 1859), 169.

4. Swift, 170; 5. H.P. Smith, ed., History of Addison County, Vermont with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of its Prominent Men and Pioneers (Syracuse, NY: D. Mason & Co. Publishers, 1886), 245.

5. Swift, 182.

6.Smith, 266.

7. Swift, 170.

8. Swift, 186.

9. Frederick Hall’s Statistical Account of the Town of Middlebury, 1821, Collections of Henry Sheldon Museum of Vermont History, Middlebury, Vermont.

10. Smith, 245.

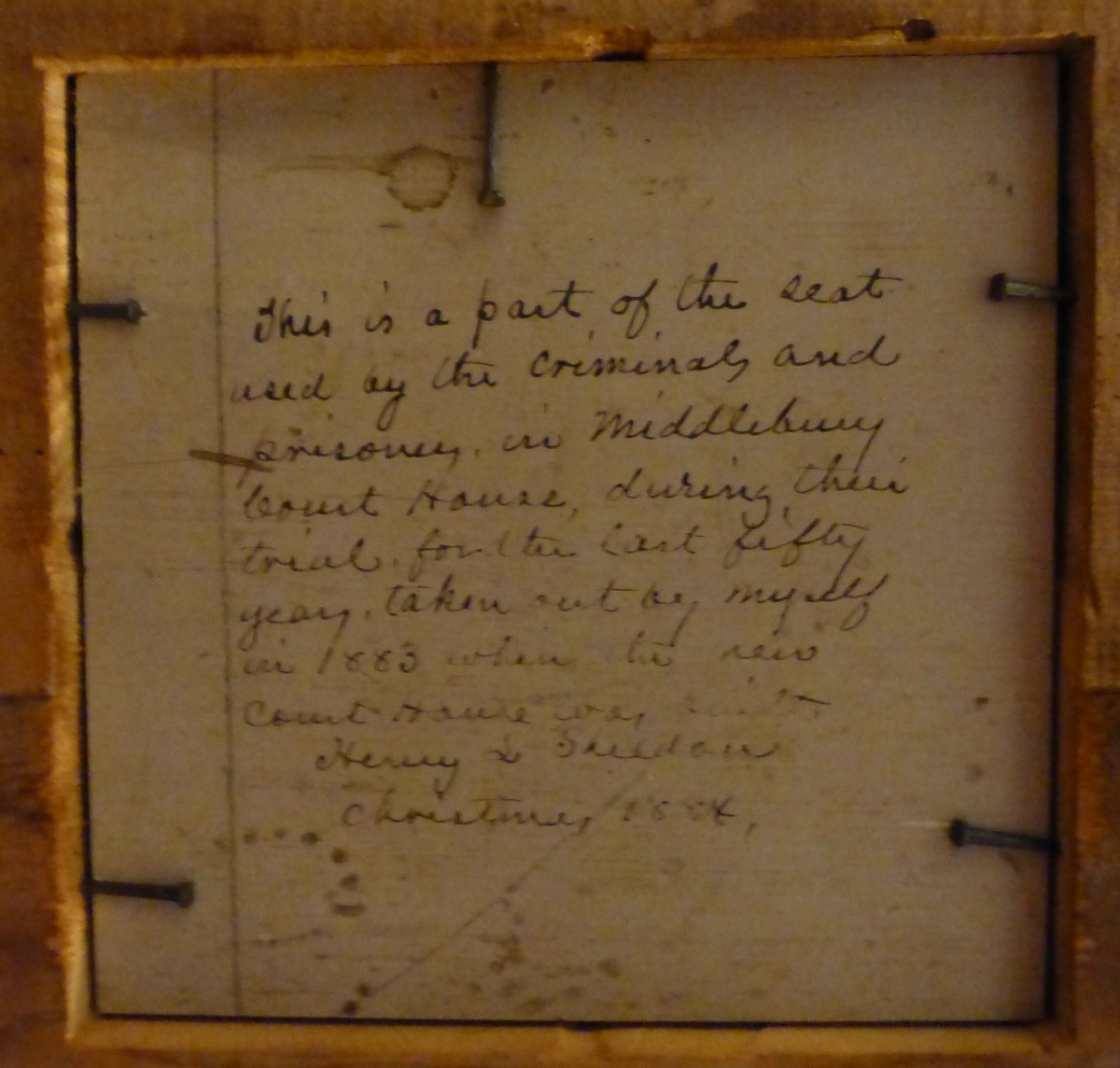

“This is a part of the seat used by the criminals and prisoners in Middlebury Court House, driving their trial for the last fifty years, taken out by myself in 1883 when the new Court House was built. – Henry L. Sheldon

“This is a part of the seat used by the criminals and prisoners in Middlebury Court House, driving their trial for the last fifty years, taken out by myself in 1883 when the new Court House was built. – Henry L. Sheldon

You must be logged in to post a comment.