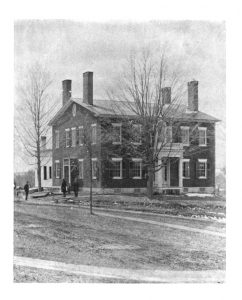

The sixth spindle acquired by Henry Sheldon was a piece of wood from the building frame of the Epaphras Miller house in Middlebury, Vermont. For Sheldon, the Ep. Miller House was of both historical and emotional significance.[1] Erected in 1811, the original wood building was constructed to be a tavern; however, for Sheldon, it contained family ties, as his uncle was the proprietor of the shop for a short period of time.[2] Throughout the 19th century, the Ep. Miller house, transformed to suit the needs of the Middlebury community, evolving along the way to aid the people of Middlebury, Vermont.

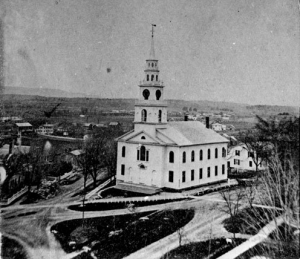

In 1793, the lot on which the Ep. Miller House would come to stand was purchased by Anthony Rhodes, who settled in Middlebury as a merchant.[3] Three years later, Ep. Miller purchased the land east of Otter Creek, and constructed a tannery in which he ran for multiple years.[4] In addition, he cleared way for the Middlebury railroad system and removed a standing property for the creation of the Baptist Church.[5]

In 1816, the Ep. Miller house, along with the surrounding green house, Willard house and Vermont Hotel, burned down in a fire.[6] Subsequently, Ep. Miller reconstructed the tavern inside a newly built brick house, which was kept by Samuel Mattocks, until Nathan Woods overtook the brick building in 1826 and aimed to cater to a more profound community need, public housing.[7] The reconstructed tavern was transformed into the reincarnated Vermont Hotel.[8] Used in this manner for twenty years, the Ep. Miller House evolved. Slowly accumulating more and more temporary residents, the house became a vital part of Middlebury.[9]

Again, in 1883, the house progressed to suit the needs of the community; however, this time, it came in the form of deconstruction.[10] In its final transformation, the Ep. Miller house was taken down in order to construct the Town Hall.[11] More recently, the land previously owned by Rhodes and split in the sale to Ep. Miller was owned by Middlebury College Professor Ezra Brainerd.

The Ep. Miller house continuously changed to fit the needs of the Middlebury community. Evolving from tavern to hotel to Town Hall, the Ep. Miller house served all aspects of the community and lives on in the formation of Middlebury as we know it today.

-Chris Bradbury ’19

Footnotes

[1] Henry Sheldon, “Sheldon’s Log Book,” 1884, Sheldon Museum Archive.

[2] Henry P. Smith and William S. Rann, History of Rutland County, Vermont: with illustrations and biographical sketches of some of its prominent men and pioneers (Syracuse, NY: D. Mason & Co., 1886), 324.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] H.P. Smith, History of Addison County, Vermont (Syracuse: D. Mason & Co., 1886), 276.

[6] Samuel Swift, History of the Town of Middlebury: In the Country of Addison, Vermont (Middlebury: A.H. Copeland, 1859), p. 258.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

You must be logged in to post a comment.