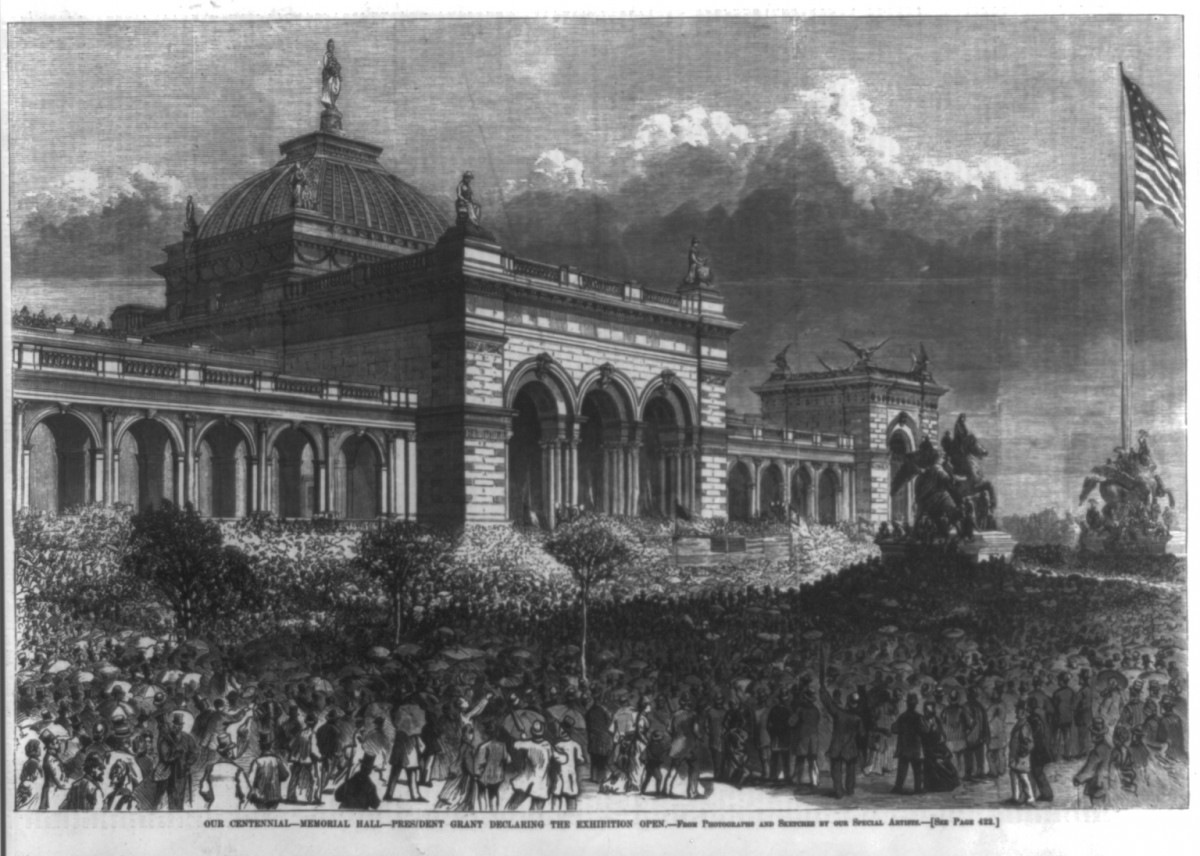

In 1876, Philadelphia hosted the “World’s Fair,” cementing the cultural presence of the United States throughout the world. One hundred years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the 1876 World’s Fair was also a celebration of the Centennial of the United States. The fair lasted from May to November of 1876, drawing international attention throughout its run.(1) Nearly nine million people came to visit and tour the “Great Exhibition,” including one-fifth of the United States population.(1) In Henry Sheldon’s relic chair, the 23rd spindle incorporates a piece of this World’s Fair. Using wood from the Memorial Building of the Centennial Exhibition, Sheldon was able to commemorate one of the largest gatherings of the nineteenth century.(2)

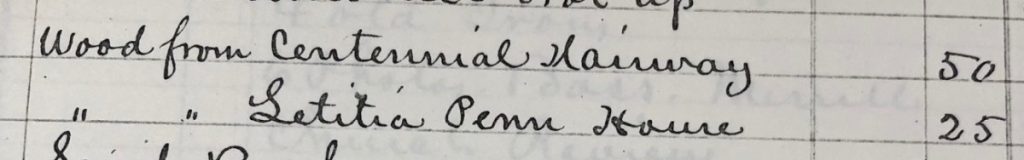

Acquisition records show that in 1884, Henry Sheldon purchased a piece of wood from the main staircase of the Memorial Building for 50 cents. This fragment was part of a bundle purchase of Philadelphia “relics” that also included wood from William Penn’s House and the Declaration House, all of which were obtained from a bookseller named William McKay Heath.(3)

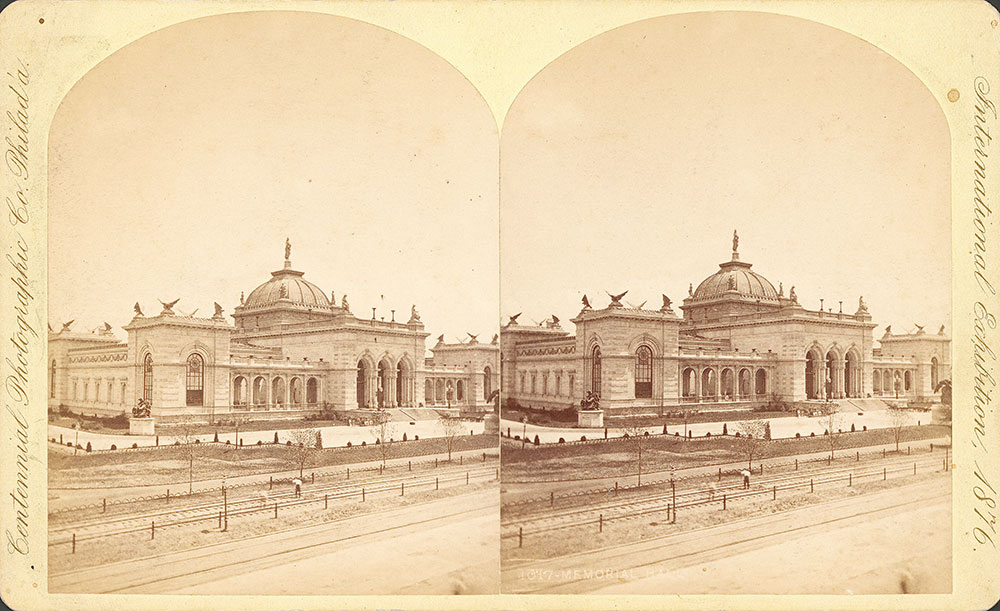

Memorial Hall is one of the few structures that still remains from the Centennial Exhibition. Originally purposed as an exhibit of international fine arts, Memorial Hall was one of the smaller exhibits and buildings.(4) Designed by H.J. Schwartzman, Memorial Hall was designed to be an opulent and lavish structure that awed all spectators.(5) Consisting of a main pavilion, a large central dome, and four smaller corner pavilions, the building was also beautifully decorated with statues designed by German sculptor A.J.M. Mueller. Sculpted eagle figures also accompanied the corners of the smaller pavilion.(6) All together the Memorial Hall building cost an estimated 1.5 million dollars to construct, making it one of the more expensive attractions at the fair.(6) Inside the building was an exhibit of international fine arts, keeping with the aesthetic theme of opulence and beauty.(7)

The Centennial International Exhibition was impressive for a multitude of reasons, though primarily for the diversity of exhibits. Seventeen states set up their own individual exhibits displaying cultural symbols from each territory. Eleven foreign countries also erected their own buildings.(8) In total there were thirty-four building structures as well as an array of restaurants, beer gardens, and cigar pavilions sprinkled throughout the fairgrounds.(6) In addition, there were over 180 structures (statues, stands etc.) which spanned more than 450 acres.(6)(7) The World’s Fair in Philadelphia was sprawling and intimidating in size, a purposeful design to symbolize the power and importance of America to the world. All together the Centennial Exposition took ten years of planning and cost over 11 million dollars, making the fair one of the biggest investments for the United States Government in the nineteenth century.(9)

Unfortunately, the very expensive investment did not pay off. In 1877 the Supreme Court ruled that the funds given by Congress for the construction of the Fair were only loans and had to be repaid. With little money, the organizers of the fair resorted to auctioning off goods from the buildings, a possible explanation for why wood from the staircase of the Memorial Building was being sold. In the years that followed, most buildings were ordered to vacate due to billiard games and other forms of entertainment overrunning most of the buildings that had been designed for educational purposes.(9)

However, the Fair should not be remembered for its troubled financial legacy. One of the more impressive feats of the fair was the role women played. Ahead of its time, the fair allowed a Women’s Exhibit which showcased various patents and inventions by women since the Declaration of Independence. Led by the great-granddaughter of Benjamin Franklin, Elizabeth Duane Gillespie, the Women’s Pavilion displayed more than eighty inventions that women had created over the last hundred years. Some of the patents included were the dishwasher, self-heating iron, and the patent for interlocking bricks.(8) Additionally, women’s rights issues such as the dress reform movement were also addressed within the exhibit.(9)

Today the Centennial Memorial Building serves as a children’s exploration museum called the “Please Touch Museum.” Aimed at creating interactive exhibits, the Please Touch Museum still maintains the original purpose of the building: education and learning (9).

Akin to Henry Sheldon’s relic chair, the Centennial Exhibition aimed to celebrate and display both American history and contemporary achievements. Although the Centennial Exhibition may have served a broader audience, both projects commemorated various American achievements and in doing so helped preserve US history.

– Spencer Tonies ’20

For further images and readings regarding the Centennial Exhibition please check out the links below:

- http://www.lcpimages.org/centennial/

- https://hsp.org/philadelphia-centennial-exhibition

- https://libwww.freelibrary.org/digital/collection/centennial-exhibition

- https://www.loc.gov/rr/news/topics/worldsPhila.html

- http://www.sil.si.edu/silpublications/worlds-fairs/WF_Format.cfm?format=Web%20Sites

For more on the architecture of Memorial Hall (including interior views), see:

– Historic American Buildings Survey: https://www.loc.gov/item/pa0944/

Footnotes:

1.”The Centennial Exhibition and Expansion of the Fairmount Park System,” City of Philadelphia Parks Service: https://web.archive.org/web/20180110192339/www.phila.gov/ParksandRecreation/history/departmenthistory/parksystemhistory/Pages/CentennialExhibition.aspx

2. Woods Used in the Memorial Chair, H.L. Sheldon Papers, vol. 19.

3. Sheldon, Henry. 1884. Sheldon Museum Archive. (January 17th, 2018) Acquisition Ledger

4. Stephanie Grauman Wolfe, “Centennial Exhibition (1876),” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, 2013: philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/centennial/.

5. Jeffery Howe, “1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia” Digital Archive of American Architecture, Boston College: www.bc.edu/bc_org/avp/cas/fnart/fa267/1876fair.html.

6. “Memorial Hall 1876.” Historic Details: www.historic-details.com/places/pa/phila/fairmount-park-houses/memorial-hall-1876/#identifier_2_697.

7. “Philadelphia Centennial Exposition,” Encyclopædia Britannica (10 Apr. 2008): www.britannica.com/event/Philadelphia-Centennial-Exposition.

8. Free Library of Philadelphia, “Centennial Exhibition: Exhibition Facts.” libwww.freelibrary.org/digital/feature/centennial/exhibition.

9. Sandy Hingston, “10 Things You Might Not Know About the 1876 Centennial Exhibition,” Philadelphia Magazine (10 May 2016): www.phillymag.com/news/2016/05/10/centennial-exhibition-history/.