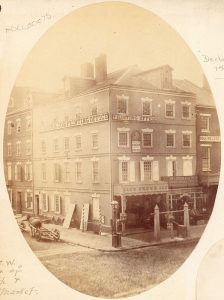

The wood for Henry Sheldon’s 24th and final spindle on his relic chair comes from the “Declaration House,” located at 700 Market Street in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a few blocks away from Independence Hall. The Declaration House, also known as the Graff House, was built by Jacob Graff in 1775 and stood as it was originally constructed for 106 years.[1] In the summer of 1776, Thomas Jefferson moved in to the second floor of the house, and drafted the Declaration of Independence there. Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were assigned to draw up the Declaration of Independence and to make it look presentable. This was an intimidating task and took the duo seventeen days to accomplish. The draft was then passed on to the Second Continental Congress, where it was further revised.[2] It was this house in which our nation’s dreams were first put onto paper, and was a monumental step toward initiating our freedom. Sheldon understood this significance and presumably wanted to enshrine a relic piece for his chair.

There is some controversy surrounding the drafting of the Declaration of Independence, specifically as to whether or not the corner of Market Street and 7th Street was the actual location of where it took place. Some speculate that it might actually be 702 Market St, while others say it was on a completely different intersection.[3] Some of the conjecture has died down since letters from Thomas Jefferson were discovered, confirming the Graff House as the location of where the Declaration was drafted. However, this may have affected Sheldon and his quest to procure spindles from across the nation. It is unknown from exactly where inside the house the relic was procured.

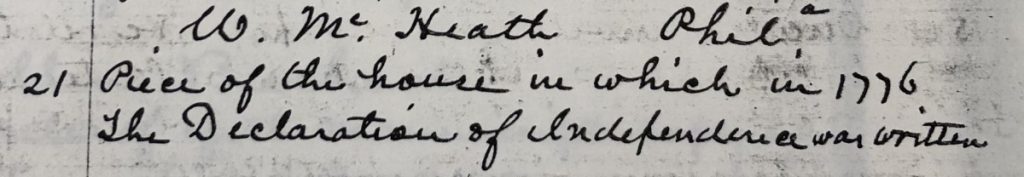

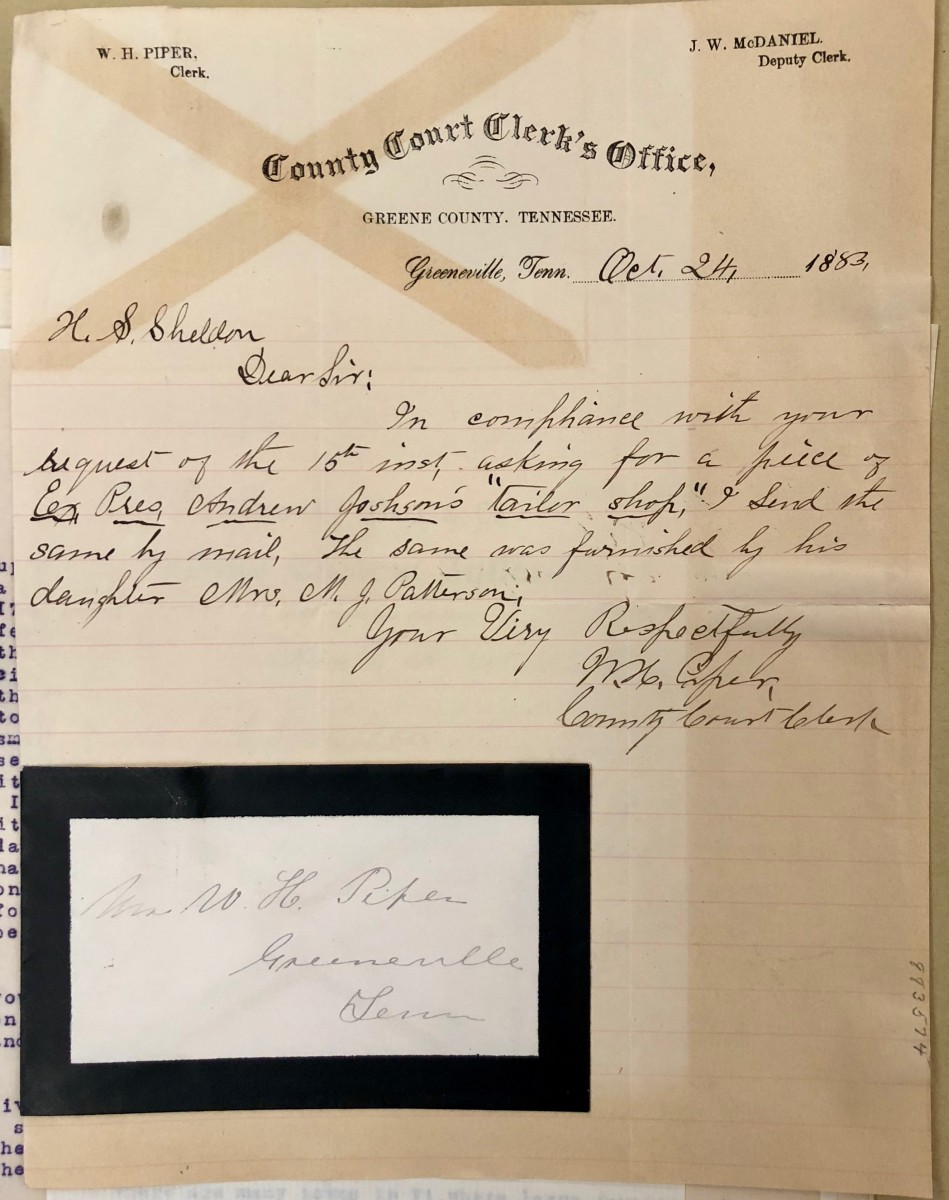

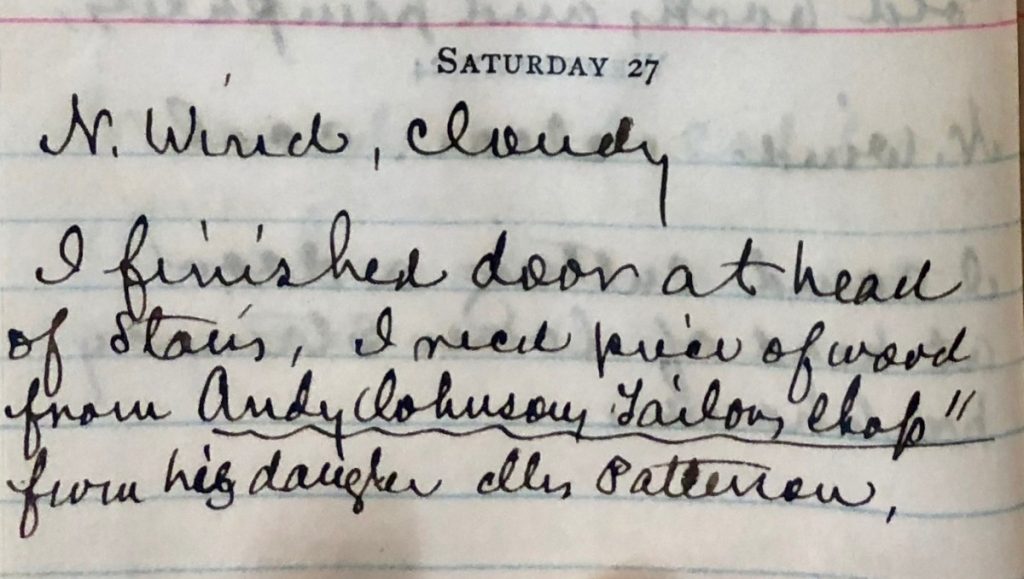

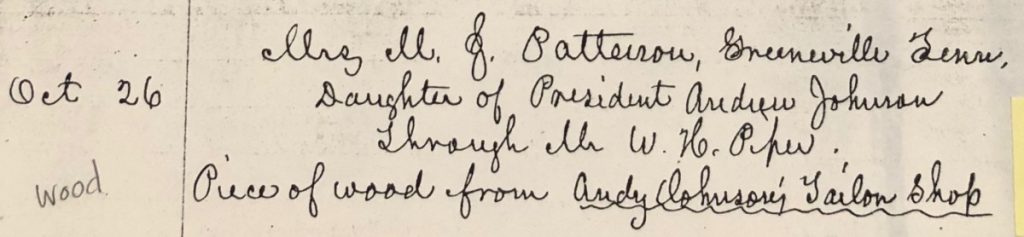

Of the 24 spindles on the chair, three come from Philadelphia. With the spindles being collected from all across the nation, Sheldon clearly wanted to show the significance the city of Philadelphia had. While Sheldon purchased the other two Philadelphia relics, from the William Penn House and the Centennial House, the Declaration House relic seems to have been a donation, as it appears in the acquisitions ledger rather than the purchases ledger (see below). Sheldon received all three of these spindles from a man named William McKay Heath.[4]

Unlike the other spindles on the chair, the relics from Philadelphia don’t seem to have the same personal connection with Sheldon. However, these relics do hold extreme value and give a different viewpoint for Sheldon and the chair. With a majority of the spindles being from Vermont, the Philadelphia spindles give the chair a national perspective. It broadens what the chair has to offer as a piece of national relevance rather than just a piece of Vermont history. Furthermore, it allows for a much broader audience to connect with the chair.

The Declaration House was razed in 1883, around the time Sheldon purchased his relic. Yet in anticipation of the 1976 Bicentennial, Philadelphia embarked upon programs of preservation, restoration, and rebuilding. In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson was appointed Honorary Chairman of the Declaration House and was responsible for its renovations. President Johnson acquired the house and added it to the Independence National Historical Park.[6] The goal of the acquisition was to turn the House into a library of the first of its kind. The library was to be dedicated to freedom and was intended to educate the public about our growth towards this ideal.[7] In 1975, the Declaration House was rebuilt based on historic drawings and photographs, made into a museum for the public. Today, you can visit the 700 Market Street address as the house is now a historical landmark and is part of the National Park Service. Throughout all the renovations and changes that the house underwent, it is still able to evoke the 18th century elegance that Jacob Graff first constructed the house with.

– Ibrahim Nasir ’20

Footnotes:

[1] Thomas Donaldson, The House In Which Thomas Jefferson Wrote the Declaration Of Independence (Philadelphia: Avil Printing Co., 1898); Wayde Brown, Reconstructing Historic Landmarks: Fabrication, Negotiation, and the Past (New York: Routledge, 2018).

[2] John H. Hazelton, The Declaration of Independence, Its History (New York: Dodd, Mead, and Co., 1906).

[3] Donaldson.

[4]Henry Sheldon, “Acquisition Ledger,” Sheldon Museum Archive

[5] Letter from William McKay Heath to Henry Sheldon, 9 September 1884, Sheldon Museum Archive.

[6] “Independence House Gets Johnson’s Aid,” New York Times 10 Jan. 1965.

[7] Ibid.

You must be logged in to post a comment.