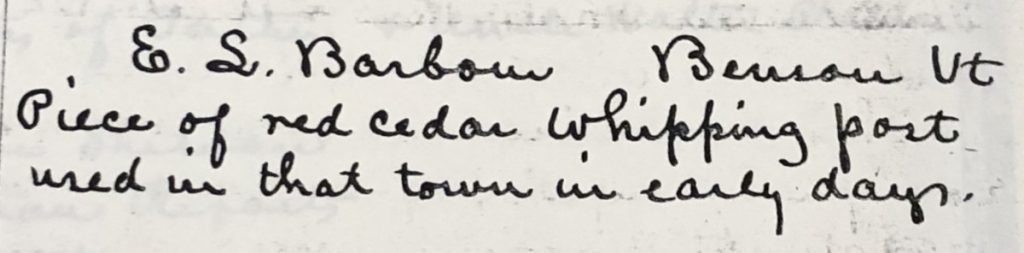

The eighteenth spindle incorporated into Henry Sheldon’s relic chair is red cedar originating from a public whipping-post in Benson, Vermont.[1] Donated by the Hon. E. L. Barbour, this piece of the Benson Whipping-Post was accepted and later incorporated by Sheldon because of the historical prominence of both the post and Egbert Benson himself.[2]

Prior to the mid-20th century, public whipping-posts were considered to be an essential adjunct of the criminal justice system with the purpose of executing judicial punishment.[3] By contemporary standards, corporal punishments of this kind are deemed to be rather severe. Particularly harsh sentencing was habitually carried out in Rutland County, Vermont, where the town of Benson is located. In 1808, a man was convicted in Rutland of distributing counterfeit money.[4] This crime was nonviolent but nonetheless threatened the sanctity of the working local capitalism; the man received a sentencing of an hour in the pillory, thirty-nine lashes at the whipping-post by a cat-o-nine-tails whip, $500 fine in addition to the prosecution fees, and seven years of hard labor in state prison.[5] The whipping was seen by then Rutland resident Amasa Pooler, who described there to be over a hundred carriages in attendance. Local residents flocked to observe the convicted criminal be stripped, lathered in rum and beaten despite the bitter cold and deep snow.[6] The event went further than a public display of justice. It was entertainment.

Whipping-posts were an essential part of public life in the 19th century. They were not merely a place of restitution, but also a landmark for governmental addresses, administration of warrants and local news.[7] While the Benson Whipping-Post did indeed serve the same purpose as neighboring whipping-posts in fulfilling these societal roles, it was incorporated into Sheldon’s relic chair perhaps also because of its historical connection to founding father Egbert Benson.

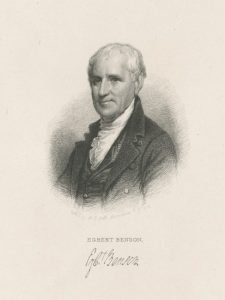

Born in New York City on June 21, 1746, renowned patriot Egbert Benson was a decorated Revolutionary War officer and law practitioner who played an instrumental role in the formation of the United States of America.[8] Benson, the third of four sons, grew up in a respected Dutch family.[9] His father, a brewer, and mother, a homemaker, lived respected middle-class lives and provided Benson a foundation for both academic and societal success.[10] Egbert Benson graduated from Kings College, New York, from now known as Columbia University, in 1765 with a law degree.[11] In 1769, he proceeded to pass the bar with relative ease and moved roughly one hundred miles north to find work in Red Hook, New York.[12]

Not long after Benson left New York City, the Revolutionary War broke out, and Benson’s focus shifted from his progression as a lawyer to his advancement as an abolitionist.[13] He led the earliest meetings of organized resistance in Dutchess County and became a figurehead of progressive enlightenment as he rallied citizens to join in the revolutionary movement.[14] As his public notoriety expanded, he cemented his influential role in public office. He was appointed first attorney-general of New York by ordinance of the May 8, 1777 convention and held this position until his resignation in 1787.[15] He drafted the vast majority of bills passed by the assembly during the war and he quickly became considered a man of insurmountable aptitude.[16] Later, he played a vital role in the adoption of the constitution, and in 1789 he was elected as one of the six representatives form New York to the first congress.[17] In 1794, he was appointed as a New York Supreme Court judge where he excelled until his resignation in 1801.[18] At this time he was appointed to chief judge in the second circuit, but he never ended up taking office and subsequently retired. Following his departure from political office, he moved to Jamaica, Queens and resided there until his death on August 24, 1833.[19]

The Benson Whipping-Post is a physical manifestation of how the material world reflects the historical past.[20] E.L. Barbour must have recognized this both when he donated the fragment to Henry Sheldon for his museum, and when he exhibited a cane made from the same material at a meeting of the Rutland Historical Society the following summer, in August 1885. Through a piece of red cedar from a seemingly conventional whipping-post, Henry Sheldon accurately conveyed the complicated histories of corporal punishment and law and order, while concurrently illustrating the impact of those associated with the post itself.

-Chris Bradbury ’19

Notes:

[1] Henry Sheldon’s Log Book, (HL Sheldon papers vol. 19), 1884, Sheldon Museum Archive.

[2] John M. Currier, Proceedings of the Rutland County Historical Society. Vol. 2. John M. Currier, 1887, p. 81

[3] Henry P. Smith and William S. Rann, History of Rutland County, Vermont: with illustrations and biographical sketches of some of its prominent men and pioneers (Syracuse, NY: D. Mason & Co., 1886), 260. See also George Ryley Scott, Flagellation; a history of corporal punishment in its historical, anthropological and sociological aspects (London: Tallis Press, 1968); Maryland Historical Society Library, “‘Only the Instrument of the Law’: Baltimore’s Whipping Post”: http://www.mdhs.org/underbelly/2013/10/03/only-the-instrument-of-the-law-baltimores-whipping-post/.

[4] Smith and Rann, 260.

[5] Smith and Rann, 261.

[6] Ibid. On histories and theories of crime and punishment (including the roles of public displays of disciplinary measures), see Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (1977), trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1995).

[7] Smith and Rann, p. 584

[8] James Kent, “Egbert Benson, Associate Justice of the New York Supreme Court, 1794-1801,” in History of Long Island, ed. Benjamin F. Thompson, 1839: https://www.nycourts.gov/history/legal-history-new-york/luminaries-supreme-court/documents/kent-bio-benson.pdf.

[9] Documentary History of the First Federal Congress of the United States of America, ed. Charlene Bickford, et al. (Columbia, S.C.: Model Editions Partnership, 2002).

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] James Kent, “Egbert Benson, Associate Justice of the New York Supreme Court, 1794-1801.” 1839.

[14] Documentary History of the First Federal Congress of the United States of America

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

You must be logged in to post a comment.