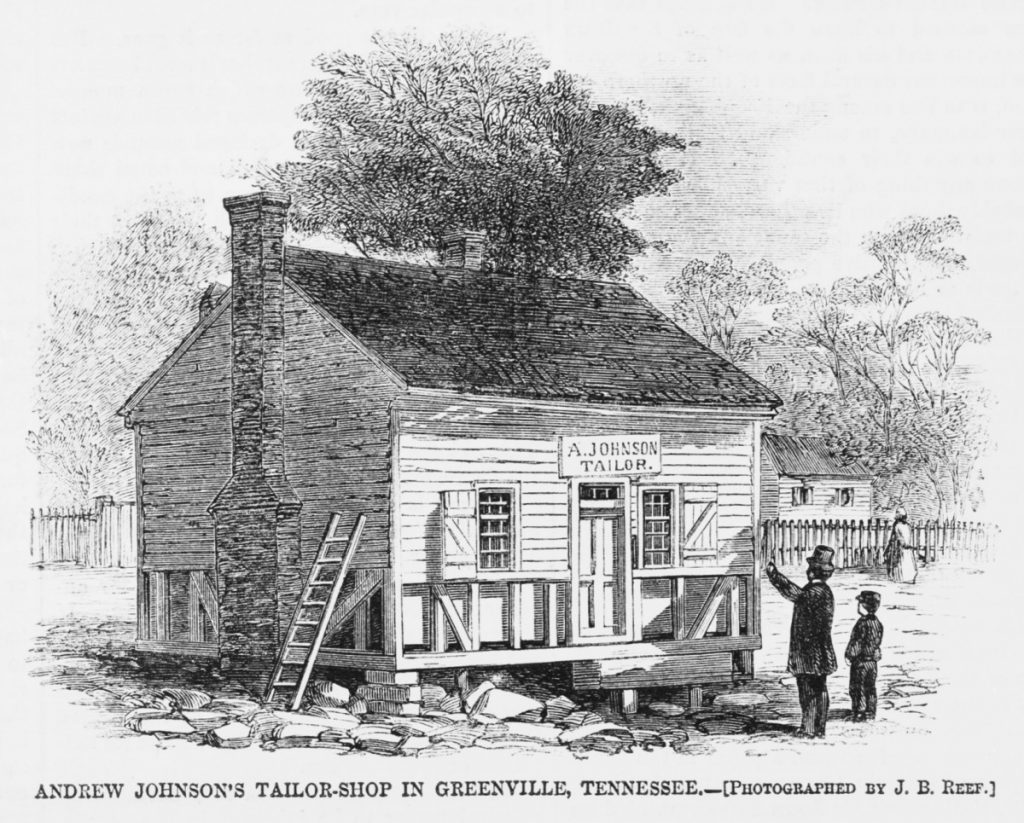

The central relic in the lower row of spindles is not finely turned with gently swelling curves, like its neighbors—instead, it is a rough-hewn, rectangular length of wood. Its inscription suggests familiarity rather than formality: “Andy Johnson’s Tailor Shop.” Yet far from being another local Middlebury connection, this relic hails from East Tennessee, and the homestead of a former President: Andrew Johnson.

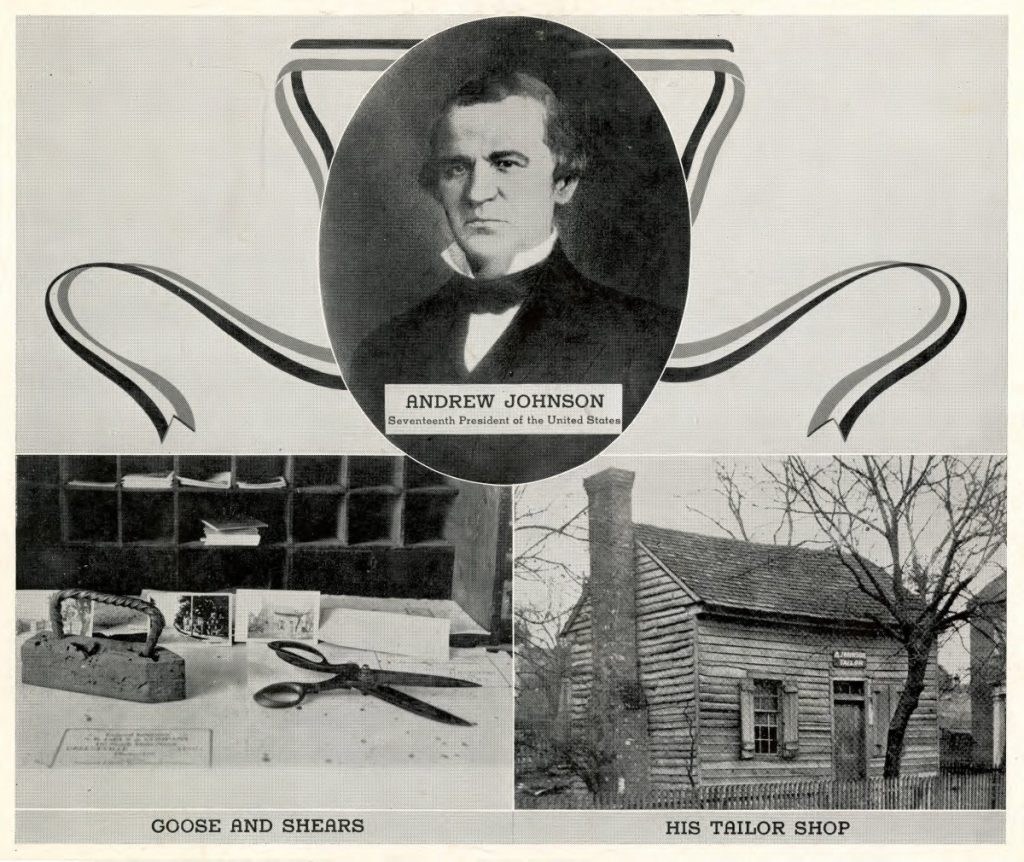

Andrew Johnson was the seventeenth President of the United States, ascending to the office after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. His tenure has been widely denounced. Serving in the aftermath of the Civil War, Johnson looked to quickly reunify the country through Reconstruction policies that were largely at the expense of Black Americans, dismantling institutions such as the Freedmen’s Bureau, which had been intended to offer material aid and secure civil rights for formerly-enslaved people. In 1868, articles of impeachment were brought against Johnson; he was the first (though not the last) U.S. President to face an impeachment trial. After leaving office, he returned to Tennessee, staging a comeback when he ran for and won a seat in the Senate in 1875. He died only a few months later.

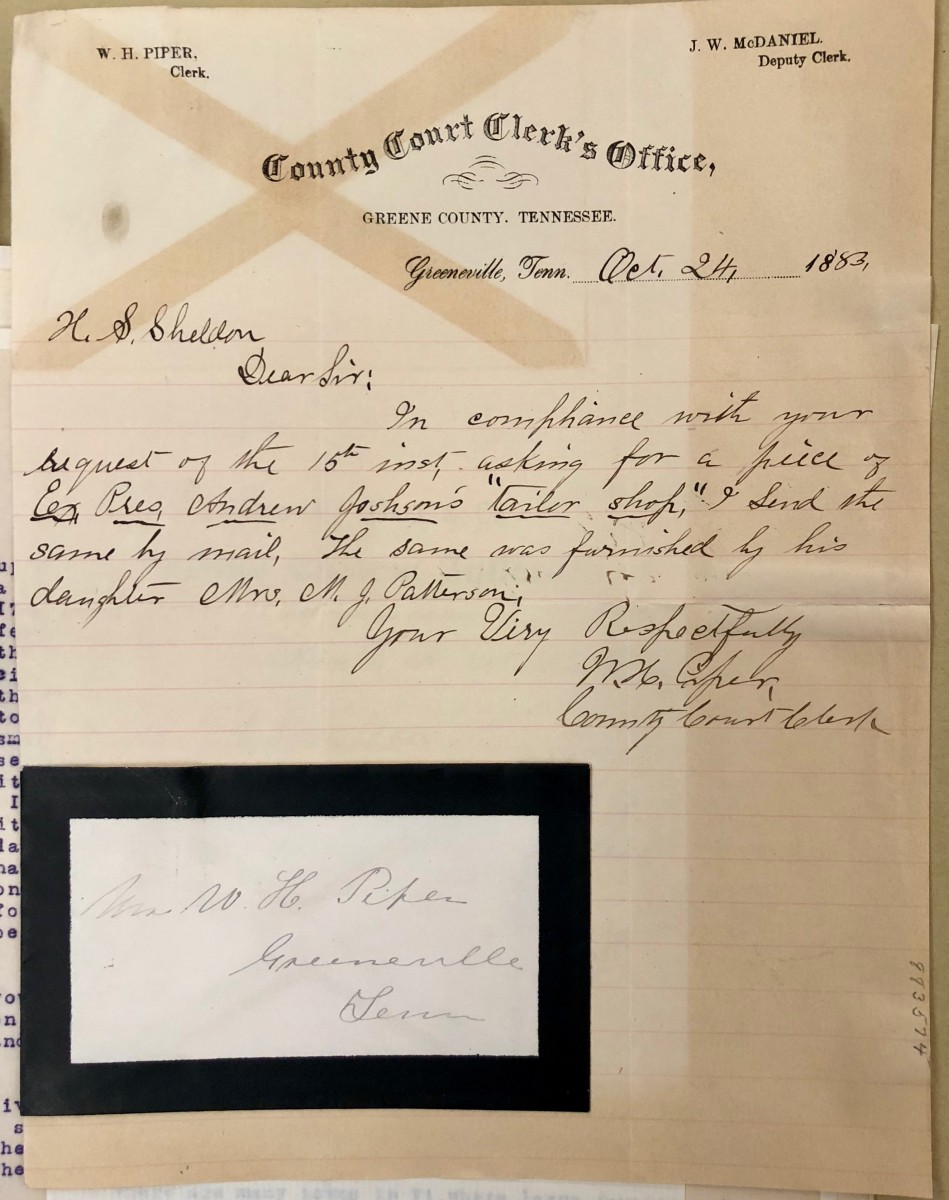

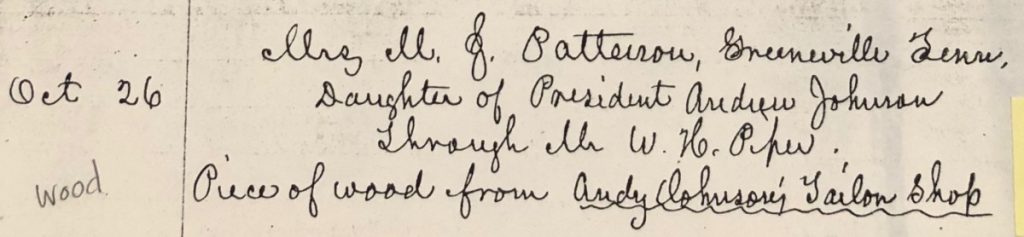

Fewer than ten years after these tumultuous events, Henry Sheldon contacted Johnson’s daughter, Martha Johnson Patterson, asking her for a contribution to his museum. Patterson had served as the primary hostess during her father’s years in the White House, acting as a de facto First Lady. In Tennessee herself, Patterson delegated the sending of the relic to W.H. Piper, the County Court Clerk of Greene County (see below).

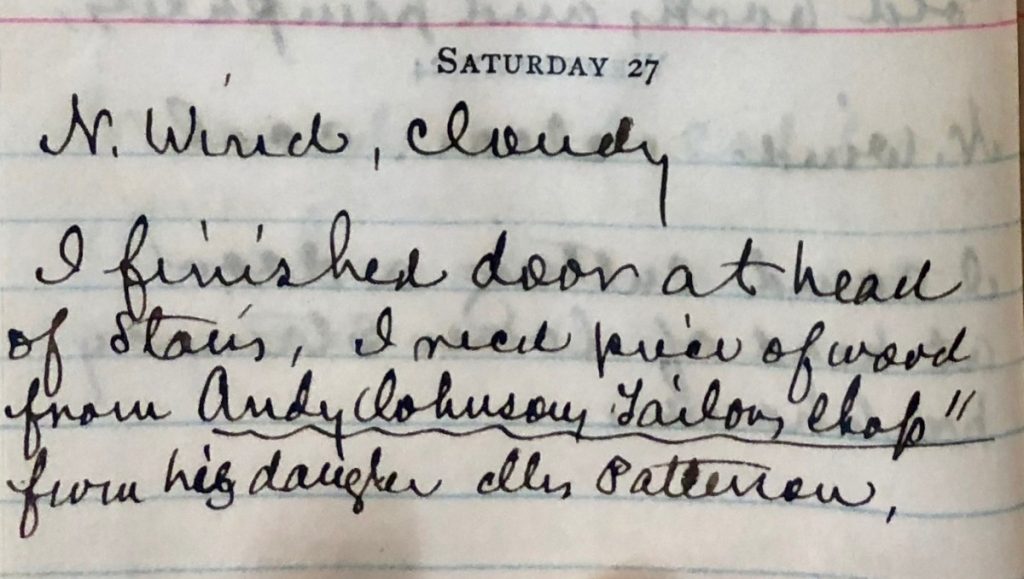

Sheldon’s excitement about receiving the relic can be seen in the enthusiastic underlining in both his diary and his acquisitions ledger, noting his receipt of the piece of wood from “Andy Johnson’s Tailor Shop.”

Like Lincoln, Johnson built much of his reputation and public persona on his humble background, highlighting his former employment as a tailor. Popular lore frequently emphasized how Johnson received his primary education not in school, but by asking people to read newspapers and books to him as he sewed.[1]

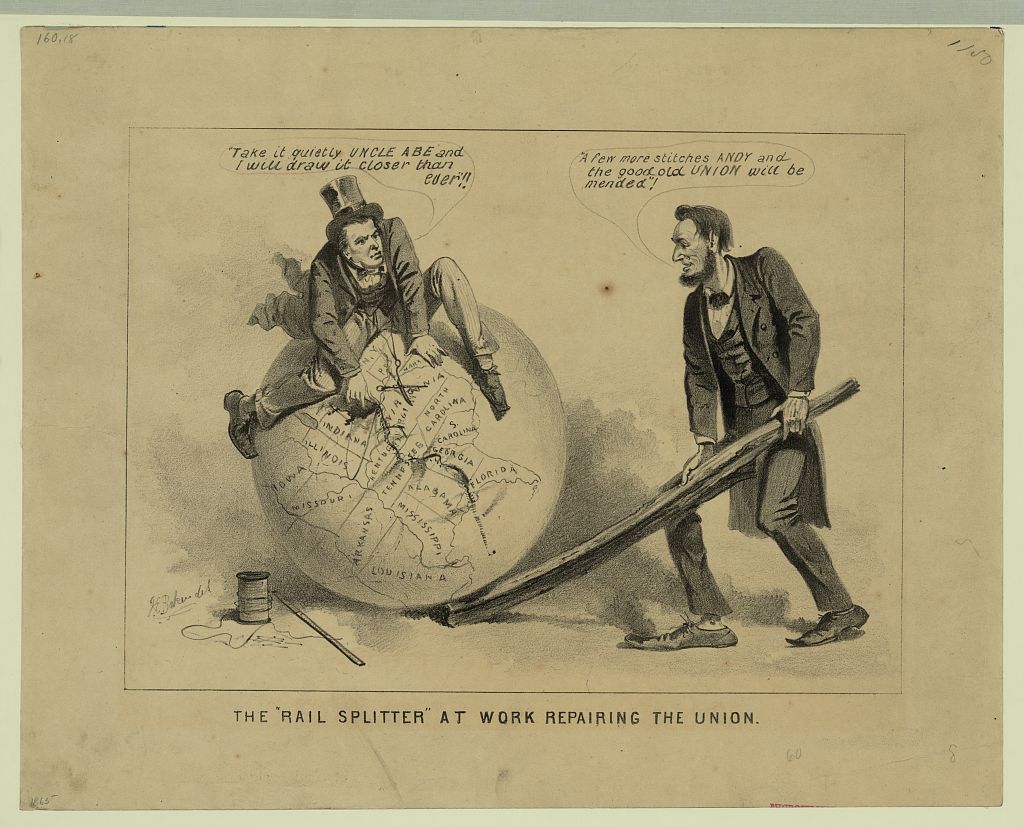

Political cartoons featured the team of Lincoln and Johnson collaborating in their roles as “rail-splitter” and “tailor” to heal the rift of the Civil War with their trades. Here, Lincoln uses a rail to hold a globe featuring the U.S. aloft as Johnson crouches atop it with shears, needle, and thread in hand, attempting to mend the rip across the country. “Take it quietly Uncle Abe and I will draw it closer than ever!!” Johnson exclaims, while Lincoln encourages him: “A few more stitches Andy and the good old UNION will be mended!”

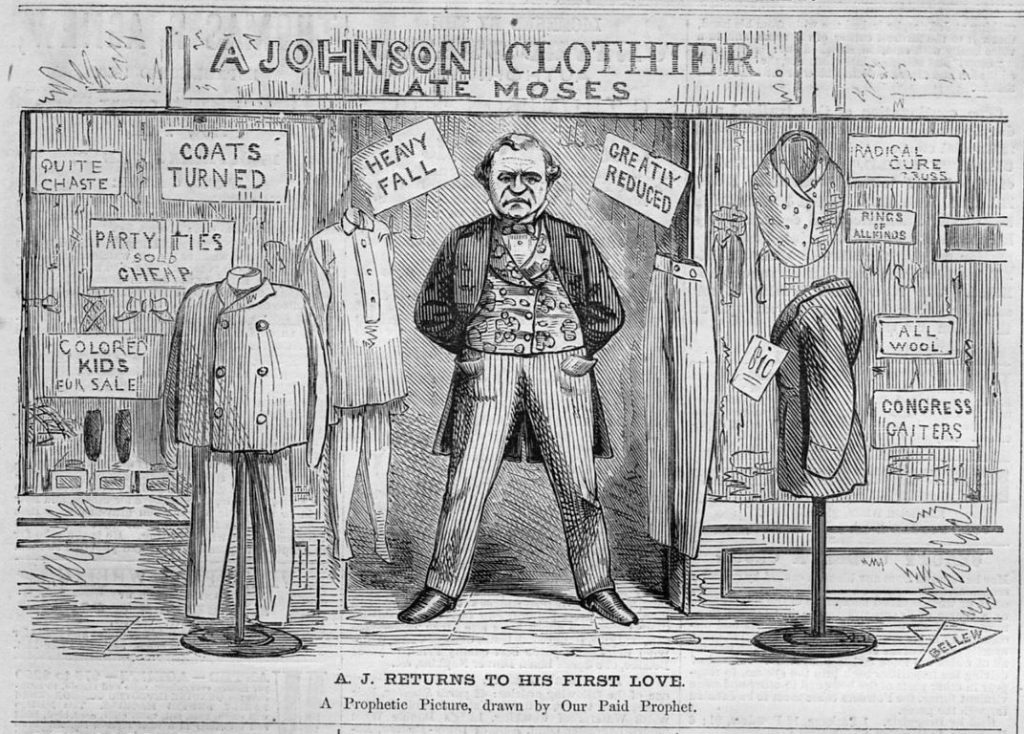

Yet other depictions spoofed Johnson’s status as a tailor, especially in the aftermath of his impeachment. In “A.J. Returns to his First Love,” Johnson stands defiantly at a storefront under the sign “A. Johnson Clothier.” The windows are filled with signs offering bargains—most of which are actually puns on the former President’s failings and reduced status: “Coats Turned,” “Party Ties Sold Cheap,” “Heavy Fall,” “Greatly Reduced,” and, most alarmingly, “Colored Kids for Sale.”

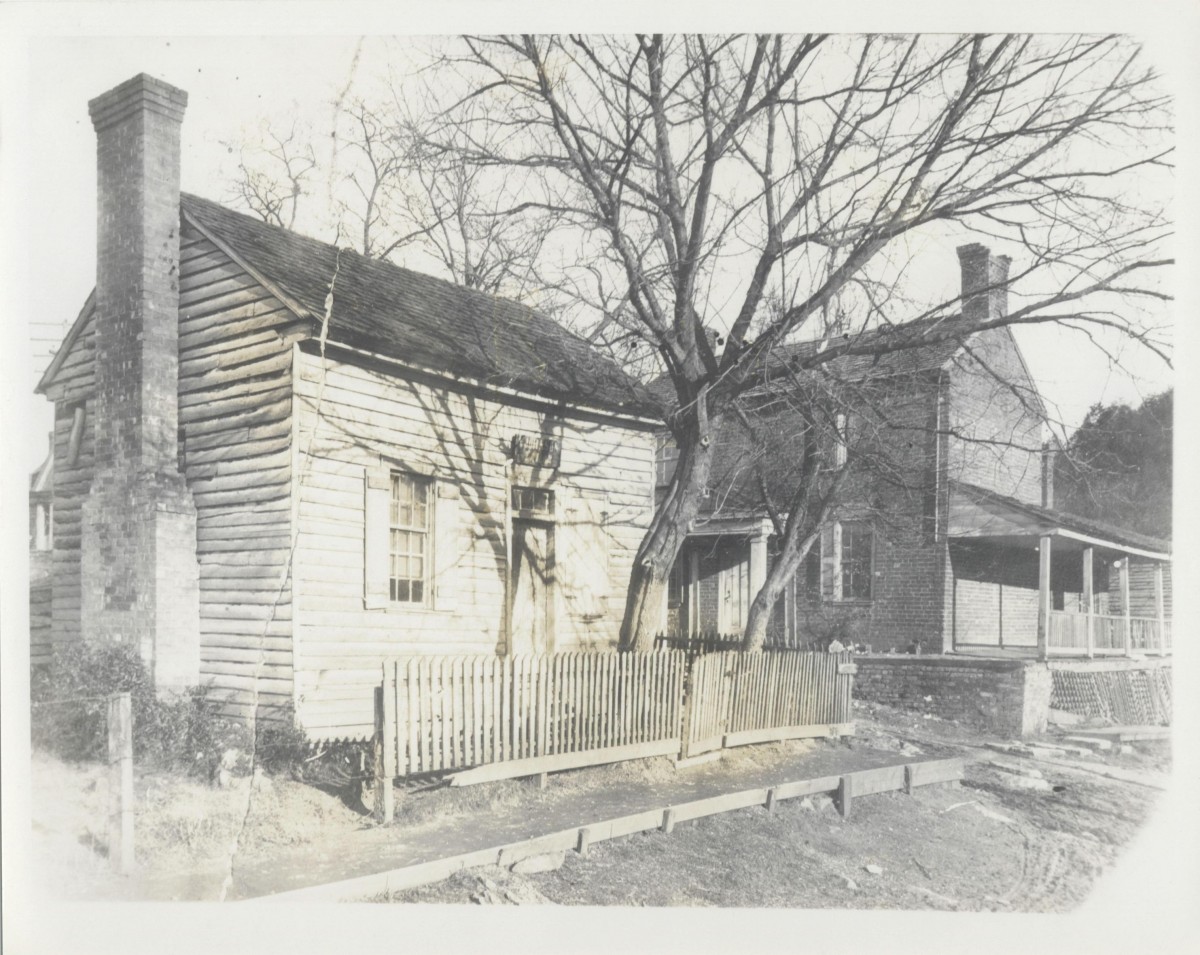

At the time Sheldon acquired the relic, Johnson’s descendants still owned the building, but it was purchased by the State of Tennessee in 1921. A few years

later (1923), the State erected a brick “Memorial Building” around the structure, in the hopes of protecting the fragile building from the elements. It was designated a national monument in 1941 and is open to the public as part of the Andrew Johnson National Historic Site, administered by the National Park Service.

The Tailor Shop was still seen as an icon of Tennessee history in the 1930s, when the structure inspired a parade float; descendants of Johnson donned period costumes and rode through town as though perched on the lawn of the building, painstakingly reproduced. Even though the structure had been sheltered from open viewing, protected by the “Memorial Building,” it was still very present in the public imagination.

-Ellery Foutch, Assistant Professor

[1] See, for example, “President Andrew Johnson,” Harper’s Weekly IX, no. 437 (13 May 1865), 289.

Further reading:

Online exhibition with artifacts from Andrew Johnson Historic Site: https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/tgKy36vEeIZxLg

“An Historical Tailor Shop,” The Tailor XII, no. 2 (Sept. 1901), 4-5:

Cameron Binkley, Andrew Johnson National Historic Site: Administrative History (National Park Service, 2008): http://npshistory.com/publications/anjo/adhi.pdf

Paul H. Bergeron, Andrew Johnson’s Civil War and Reconstruction (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2011).

Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution (New York: HarperCollins, 1988).

Annette Gordon-Reed, Andrew Johnson (New York: Times Books, 2011).

Hugh A. Lawing, “Andrew Johnson National Monument,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 20, no. 2 (June 1961): 103-119.

Evan Phifer, “Martha Johnson Patterson: Hostess of the Andrew Johnson White House,” White House Historical Association, 13 Mar. 2017: https://www.whitehousehistory.org/martha-johnson-patterson-hostess-of-the-andrew-johnson-white-house

Glenna R. Schroeder-Lein and Richard Zuczek, Andrew Johnson: A Biographical Companion (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2001).

James Stewart, Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln’s Legacy (new York: Simon and Schuster, 2009).

Hans L. Trefousse, Andrew Johnson: A Biography (New York: W.W. Norton, 1989).

You must be logged in to post a comment.