There are many ways to interpret a work of art. The museum’s Label Talk series encourages visitors to reflect upon and voice their own interpretations of specific artworks, such as this pairing of a lustreware tile created by an Ilkhanid artisan in the 13th century to adorn a structure and an oil sketch created by Jean-Léon Gérôme in the late 1800s in preparation for a finished painting. Several members of the Middlebury community have offered their personal or professional reactions to this artwork, and those reactions are displayed adjacent to the works on the wall in the galleries. In publishing them here in this post as well, we hope these perspectives will inspire you to share your own responses to these works of art in the comments below.

We look forward to reading, hearing, seeing, and/or experiencing your responses.

This glazed ceramic tile would originally have been one in a row of tiles. The presence of birds behind the script, which may be in Arabic or Persian, suggests that this tile would not have adorned a mosque, where figurative imagery is forbidden. Rather, it may have decorated a private house or a shrine to a Sufi saint.

Like much Islamic art, this tile’s colors, textures, and patterns evoke a particularly famous saying of the Prophet Muhammad, “God is beautiful and loves beauty.” It employs two of the three most common artistic motifs that flourish in Muslim-majority civilizations: calligraphy and vegetal patterns. The third commonly used motif—geometric shapes—though not seen here, can be found in other ceramic works in the museum’s collection.

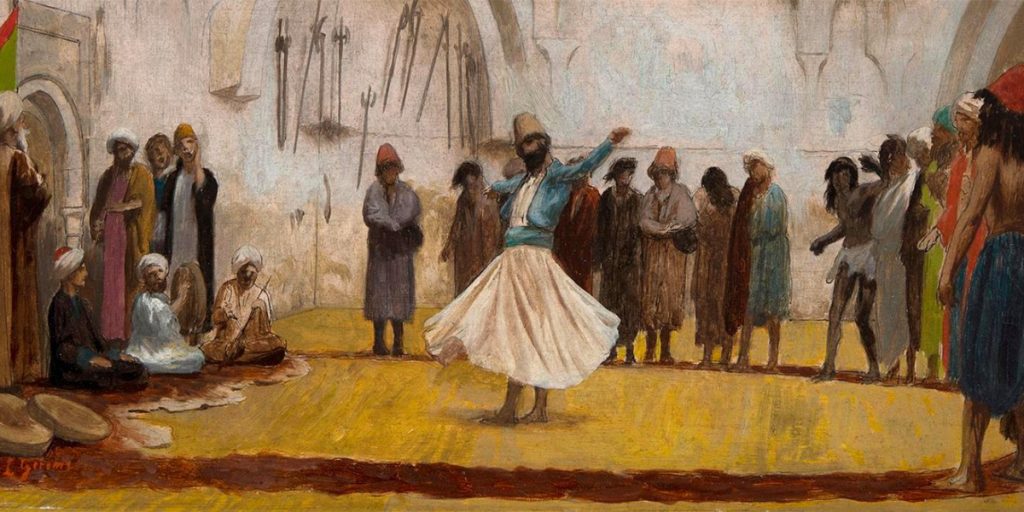

French painter Jean-Léon Gérôme is best known for subjects derived from his travels in Cairo, Jerusalem, and Constantinople—at the time part of the Ottoman Empire and popular destinations for European religious pilgrims and tourists alike. This preparatory sketch for a painting suggests Gérôme’s engagement with Orientalism, a predominantly European and American framework that imagined and represented the cultures, religions, and people of the Near East as distinctly different from their western counterparts. Gérôme’s focus on a ritual associated with Sufism, the mystical tradition of Islam, would have delighted European viewers with its transcendental subject matter and rich detail, including the pseudo-Arabic calligraphy of the tiles in the upper right.

Looking for a different way to interact with The Whirling Dervish? Try your hand at the virtual jigsaw puzzle below. Click the image, or follow this link to open the puzzle on our Jigsaw Planet page.

Audience Responses

Both this tile and this painting are related to the Sufi–or mystical–tradition of Islam, which embraces heavenly and earthly motifs. Although both works of art summon the transcendent, they seem to possess distinct commentary on how transcendence is achieved. In the tile, for example, the repeated arabesque design at the top evokes a sense of the infinite, while the rich decoration, color, pattern, and calligraphy in its lower portion drown the spectator in a spiritual lushness.

By contrast, the more muted hues of the painting seem to accord with attempts to reach spiritual states through asceticism. Seeing these works of art together reminds me that the Oneness of God can, paradoxically, be experienced in many different ways.

—Saifa Hussain, Muslim Chaplain

Viewing these artworks in rural Vermont makes me think about the complex ways in which knowledge of Islam has spread around the world. The calligraphic tile, made in Iran in the 13th century, brings to us not just a piece of history from hundreds of years prior, but also a renewed image of Islam and its messages. In a world where Islam is still largely and inaccurately represented by violence, we see a piece of art whose literal message is peace and tranquility.

Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Whirling Dervish depicts a spinning Sufi who is partaking in a ritual intended to bring one closer to God. As the man releases his body and mind in the pursuit of that which is infinite, onlookers view him with curiosity and intrigue. Thinking about the reactions of people looking at this painting, first in Paris and now in Middlebury, I am struck by a contradiction: although the Sufi community never sought fame, their very personal act of spirituality has become a subject of global interest. But how does fascination become understanding?

—Tanzim Ahmed ’22

The color of this tile reminds me of the famous mosque in my hometown of Tabriz, Iran, known as the Blue Mosque because of the thousands of turquoise-blue tiles adorning it. Although I would like to read the Persian/Arabic calligraphy, I cannot because it appears to be in the middle of a longer sentence or verse. This makes me think about the hundreds of tiles missing from the Blue Mosque today. It also makes me ponder the original and current context of this tile. I wonder if it feels alone and objectified here, separated from the company of similar tiles, which together once made it possible for worshippers to be touched by transcendence.

Some of the details in the painting of a Sufi samaʿ (a ritual involving ecstatic remembrance of God, aided by sacred music and dance), which tends to happen in a Sufi lodge on a regular basis, are accurate. Other aspects puzzle me, including the variety of clothing and orderliness of what should be a chaotic scene. I suspect this painting was not simply a representation of reality on the ground, but partly imagined or even staged. Why these changes, and with what impact?

—Ata Anzali, Associate Professor of Religion