![]() William Wegman is known throughout the world for his inventive and witty photographs featuring his Weimaraner dogs in a variety of whimsical poses and guises. October 1981, Rangeley, Maine is a portrait of his first model, a dog named Man Ray, hidden under a layer of fall leaves. Man Ray sits below a sign forbidding hunting, trapping, or firearms that has ironically been used for target practice. A breed employed as hunting dogs, this camouflaged Weimaraner seems dressed to defy the edict, although his hunched pose conveys a mood of resignation.

William Wegman is known throughout the world for his inventive and witty photographs featuring his Weimaraner dogs in a variety of whimsical poses and guises. October 1981, Rangeley, Maine is a portrait of his first model, a dog named Man Ray, hidden under a layer of fall leaves. Man Ray sits below a sign forbidding hunting, trapping, or firearms that has ironically been used for target practice. A breed employed as hunting dogs, this camouflaged Weimaraner seems dressed to defy the edict, although his hunched pose conveys a mood of resignation.

For Wegman, Maine is a kind of Eden, offering escape from his busy life in New York. As he puts it, “Nothing bad happens in Maine….”[footnote]For a delightful romp through Wegman’s fascination with nature, see William Wegman, Hello Nature (Brunswick, Maine: Bowdoin College Museum of Art, 2012).[/footnote] He often works in the fall, posing Man Ray’s successors in bucolic settings. Wegman first encountered the Rangeley Lakes Region as a teenager, and he has spent summers there for over three decades. Nature has also played an important part in Wegman’s art, going back to his book, Field Guide to North America and Other Regions, published in 1993, which featured paintings, drawings, and essays about the natural world.

Like the work of Robert and Shana ParkeHarrison, Wegman’s oeuvre is marked by a purposeful naïveté that combines humor with a deeper critique of ways that nature has been both revered and altered by humans.

ving, breathing things. They are born when the conditions are right, they gain strength as they grow, they fight against their environment to stay alive, they change form as they age, and eventually they die. Sounds familiar.”[footnote]Quoted in Barbara Davidson, “reframed: In conversation with fine art photographer Mitch Dobrowner, Los Angeles Times, June 5, 2012.

ving, breathing things. They are born when the conditions are right, they gain strength as they grow, they fight against their environment to stay alive, they change form as they age, and eventually they die. Sounds familiar.”[footnote]Quoted in Barbara Davidson, “reframed: In conversation with fine art photographer Mitch Dobrowner, Los Angeles Times, June 5, 2012.

Eliot Porter took up color photography at a time when it was widely considered “too literal,” and thus unsuitable for artistic images. His book, In Wildness is the Preservation of the World, marked a turning point in the acceptance of fine art color photography. The book was the first of many color books that the Sierra Club would publish by a variety of artists, and the first of twenty-five monographs of color photos Porter would produce.

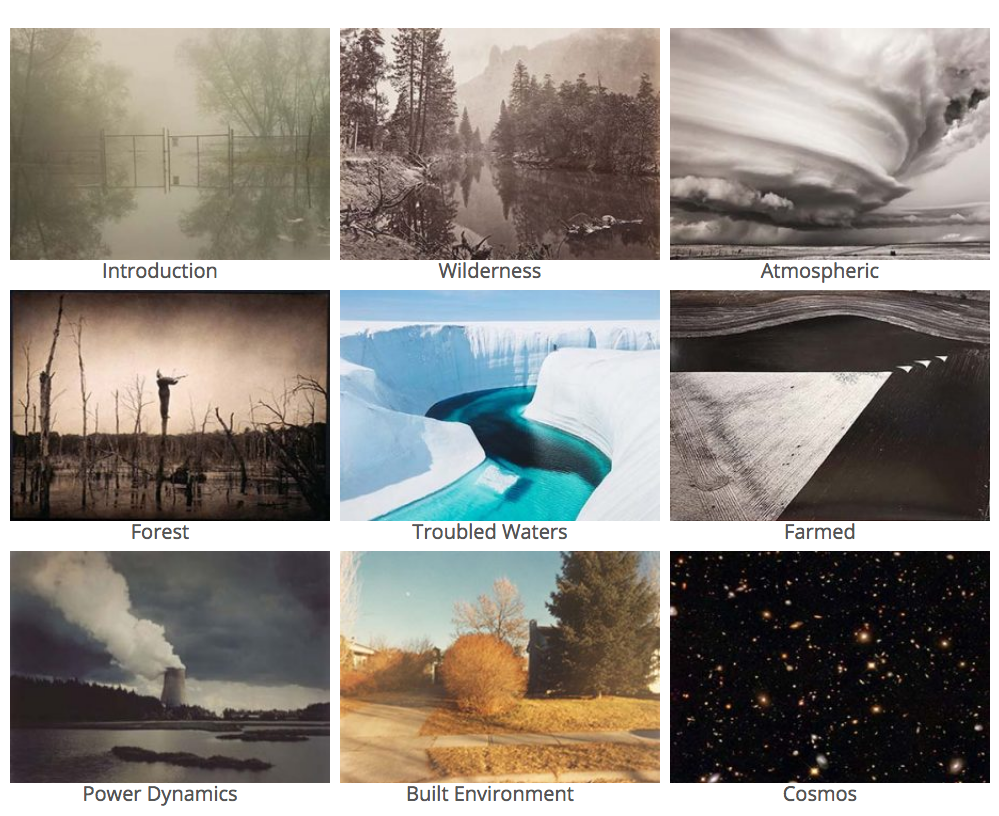

Eliot Porter took up color photography at a time when it was widely considered “too literal,” and thus unsuitable for artistic images. His book, In Wildness is the Preservation of the World, marked a turning point in the acceptance of fine art color photography. The book was the first of many color books that the Sierra Club would publish by a variety of artists, and the first of twenty-five monographs of color photos Porter would produce. Home Page: The home page displays the eight sections of the exhibition. When you enter a section of the exhibition, tap on that category and you will be taken to the photographs in that section. There is an introduction—be sure to scroll down to see if there is a video accompanying it—and discussions of individual photographs that can be accessed by tapping on the pictures. Again, be sure to scroll all the way down on those individual pages.

Home Page: The home page displays the eight sections of the exhibition. When you enter a section of the exhibition, tap on that category and you will be taken to the photographs in that section. There is an introduction—be sure to scroll down to see if there is a video accompanying it—and discussions of individual photographs that can be accessed by tapping on the pictures. Again, be sure to scroll all the way down on those individual pages.