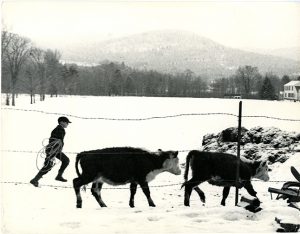

One of the best-known photographs of the Depression Era, Arthur Rothstein’s Dust Bowl Cimarron County, Oklahoma depicts a farmer and his two children fighting against the elements during a dust storm.[footnote]The photograph is alternately titled Fleeing a dust storm. Farther Arthur Coble and sons walking in the fact of a dust storm, Cimarron County, Oklahoma.[/footnote] Rothstein later remembered, “The farmer and his two little boys were walking past a shed on their property, and I took a photograph of them with the dust swirling all around….it showed an individual in relation to his environment.”[footnote]Arthur Rothstein, Words and Pictures (New York: American Photographic Book Publishing Co., 1979), 8.[/footnote]

One of the best-known photographs of the Depression Era, Arthur Rothstein’s Dust Bowl Cimarron County, Oklahoma depicts a farmer and his two children fighting against the elements during a dust storm.[footnote]The photograph is alternately titled Fleeing a dust storm. Farther Arthur Coble and sons walking in the fact of a dust storm, Cimarron County, Oklahoma.[/footnote] Rothstein later remembered, “The farmer and his two little boys were walking past a shed on their property, and I took a photograph of them with the dust swirling all around….it showed an individual in relation to his environment.”[footnote]Arthur Rothstein, Words and Pictures (New York: American Photographic Book Publishing Co., 1979), 8.[/footnote]

Although the title leads viewers to believe that the photograph was taken during the height of a dust storm, the photograph was actually a reenactment. A few years after taking the picture, the photographer described how he directed the man and his boys to act out what a storm would be like. He asked the boy on the right to put his arms over his eyes and the father and older son to lean forward as if walking into a powerful storm. The dilapidated shed behind them speaks to the poverty of the times, although in reality the family’s barn and farmhouse were much sturdier structures. While the photograph captures the dire circumstances in which many farmers found themselves, it is the result of what Rothstein called “direction in a picture story” rather than a document of an actual dust storm.[footnote]James Curtis, Mind’s Eye, Mind’s Truth: FSA Photography Reconsidered (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1989), p. 83.[/footnote]

Listen as Professor of History and Environmental Studies, Kathryn Morse, discusses the photograph within the context of the Dust Bowl and Great Depression:

https://vimeo.com/214856203