![]() In 1964, the United States Congress passed the Wilderness Act, which established a national wilderness preservation system composed of federally owned areas designated by Congress as “wilderness areas.” The Act defined wilderness as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” With panoramas of glowing mountain ranges and thundering waterfalls devoid of any human presence, the photographs of Ansel Adams have come to represent the epitome of wilderness imagery.

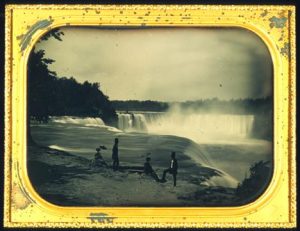

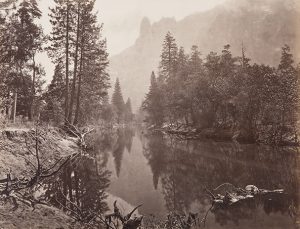

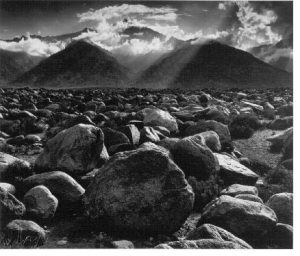

In 1964, the United States Congress passed the Wilderness Act, which established a national wilderness preservation system composed of federally owned areas designated by Congress as “wilderness areas.” The Act defined wilderness as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” With panoramas of glowing mountain ranges and thundering waterfalls devoid of any human presence, the photographs of Ansel Adams have come to represent the epitome of wilderness imagery.

By the early 1970s, however, a younger generation of photographers that included Robert Adams (no relation), Frank Gohlke, Joe Deal, Lewis Baltz and others began to take issue with this notion of nature. Deriding Ansel Adams’ views of Yosemite as “sappy” (Deal’s word) and Romantic, they photographed grain elevators, suburban housing developments at the base of mountain ranges, urban architecture and parking lots featured in the New Topographics exhibition at the George Eastman House in 1975.

In more recent decades, scholars have re-evaluated the very notion of wilderness, arguing that the concept of uninhabited, pristine nature itself is a complex cultural construction that ignores the native peoples who had lived on “wilderness” lands for centuries, as well as privileging human beings over other forms of life. Moreover, critics argue that fetishizing distant wild locales absolves us of concern for places and marginalized people closer to home. As historian William Cronon wrote in 1995, “wilderness embodies a dualistic vision in which the human is entirely outside the natural,” adding “to the extent that we live in an urban-industrial civilization but at the same time pretend to ourselves that our real home is in the wilderness, to just that extent we give ourselves permission to evade responsibility for the lives we actually lead.”[footnote]William Cronon, “The Trouble with Wilderness,” in Carolyn Merchant, Major Problems in American Environmental History, 2nd ed. (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005), 385-86.[/footnote]

A number of photographers working today who are represented in this exhibition, including Nigerian photographer George Osodi, have replaced the idealized wilderness with the realities of environmental degradation. While earlier photographers such as Ansel Adams used their work to argue for wilderness conservation, contemporary photographers like Osodi document issues confronting us directly.