![]() In Robert and Shana ParkeHarrison’s exhibition and book, The Architect’s Brother, the artists create an imaginary dystopia in which a sole survivor tries to mend a broken earth. In sepia-toned multi-media photographs, they envision the attempts of a figure in an ill-fitting black suit to perform such tasks as cleaning clouds, creating machines to listen to the earth, and transcribing the stories of trees. Creating visual parables about the possibility of healing the planet, the ParkeHarrisons invent a variety of absurd solutions to their bleak scenes of post-apocalyptic environmental devastation.

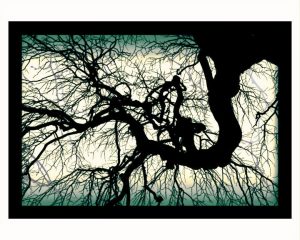

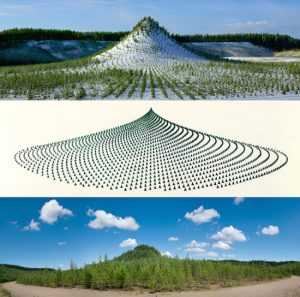

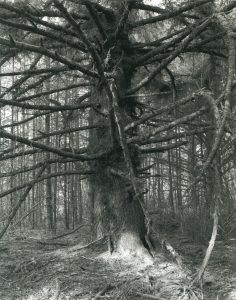

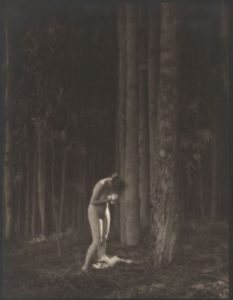

In Robert and Shana ParkeHarrison’s exhibition and book, The Architect’s Brother, the artists create an imaginary dystopia in which a sole survivor tries to mend a broken earth. In sepia-toned multi-media photographs, they envision the attempts of a figure in an ill-fitting black suit to perform such tasks as cleaning clouds, creating machines to listen to the earth, and transcribing the stories of trees. Creating visual parables about the possibility of healing the planet, the ParkeHarrisons invent a variety of absurd solutions to their bleak scenes of post-apocalyptic environmental devastation.

As the artists observe on their website, “We create works in response to the ever-bleakening relationship linking humans, technology, and nature. These works feature an ambiguous narrative that offers insight into the dilemma posed by science and technology’s failed promise to fix our problems….”[footnote]Robert and Shana ParkeHarrison, “Artist Statement,” http://www.parkeharrison.com/statement. Accessed March 20, 2017.[/footnote]

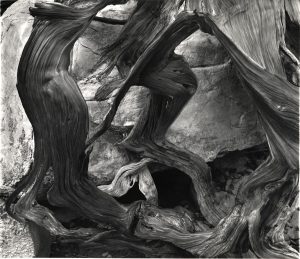

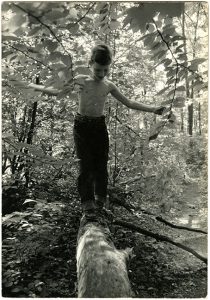

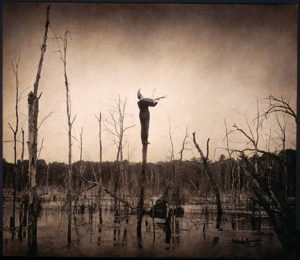

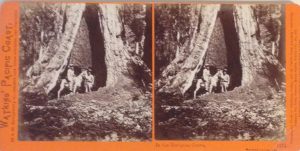

In Tree Sonata, from the subset, Earth Elegies, a figure perches on a wooden stand to serenade dead trees with a clunky, oversized stringed instrument. Wearing a straw cornucopia hat, the musician invokes themes of bounty and harvest in this bleak setting. With a style recalling the look of nineteenth-century photographs by such figures as Timothy O’Sullivan, the ParkeHarrisons use multiple paper negatives, drawing, painting, collage elements, and composite printing to create their final works.

Land and Lens guest curator Kirsten Hoving interviewed the artists about their work: