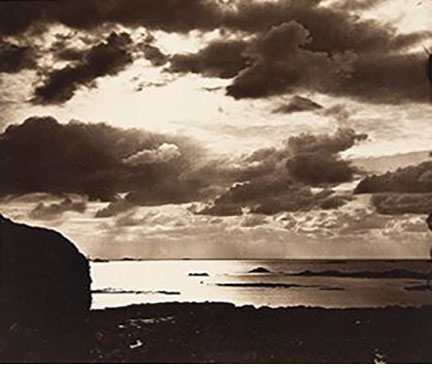

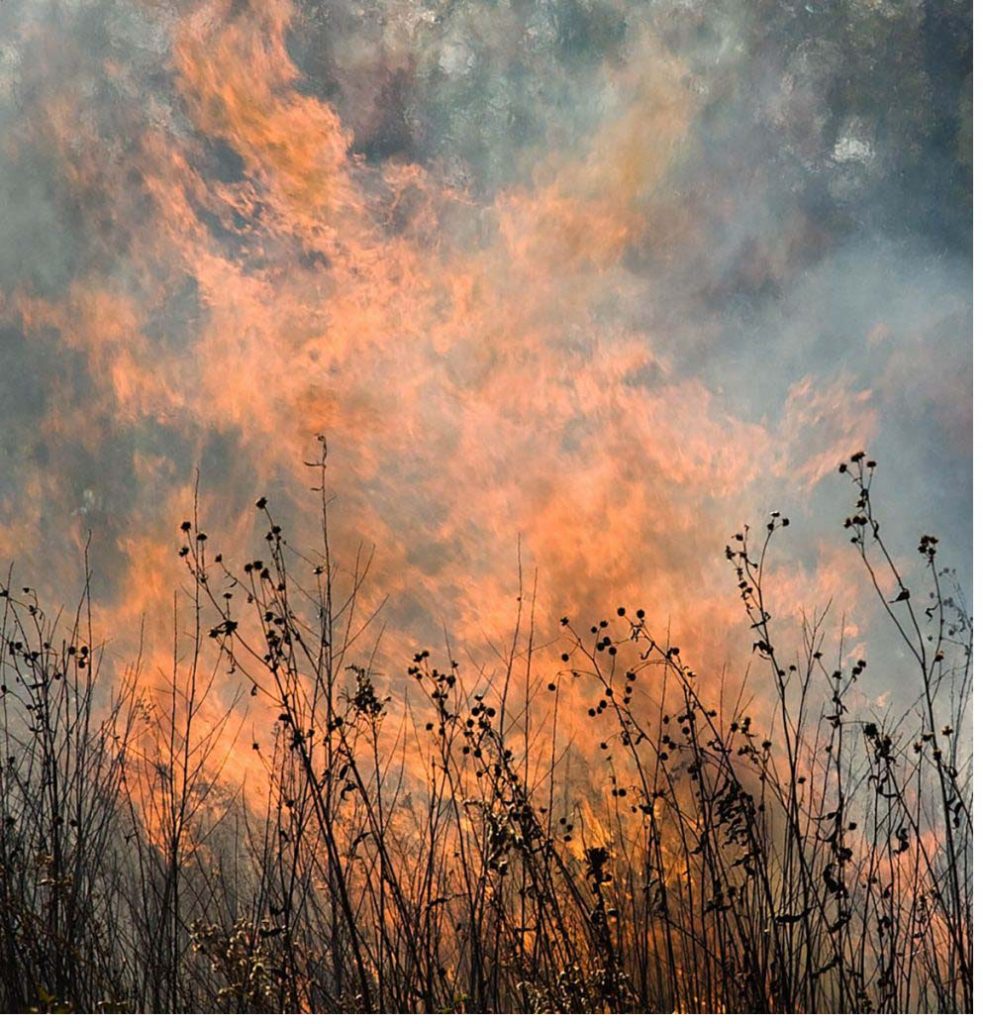

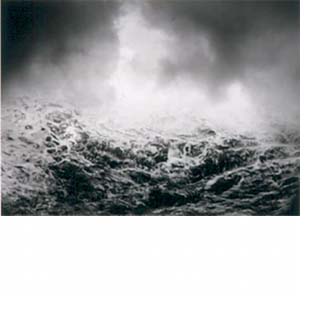

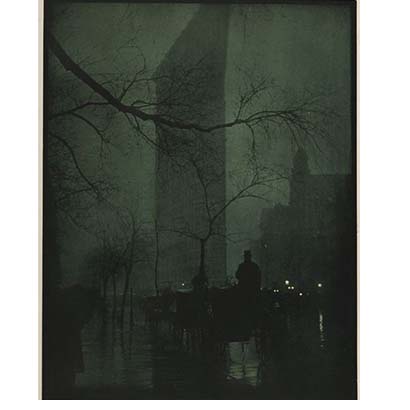

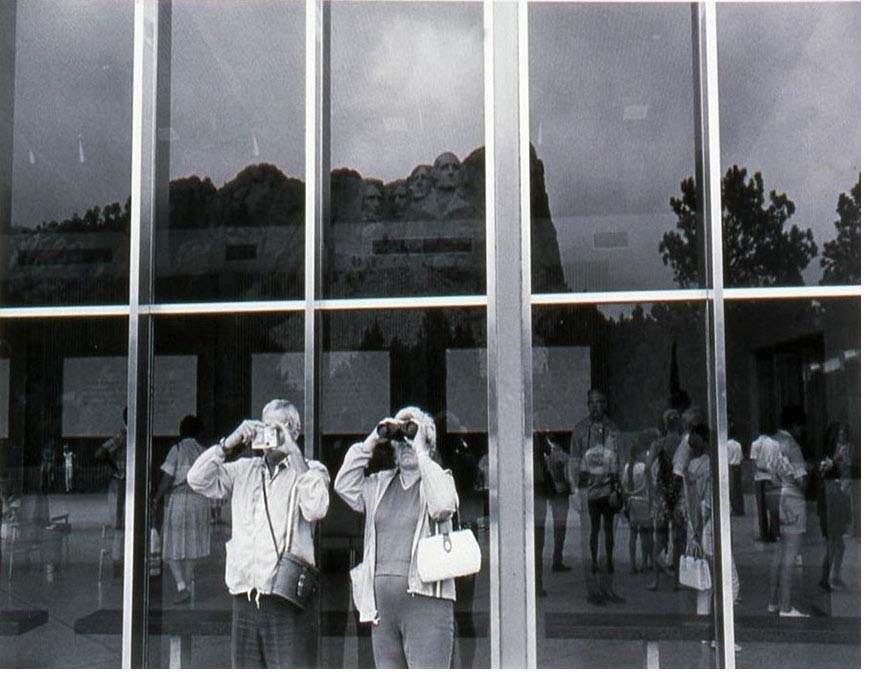

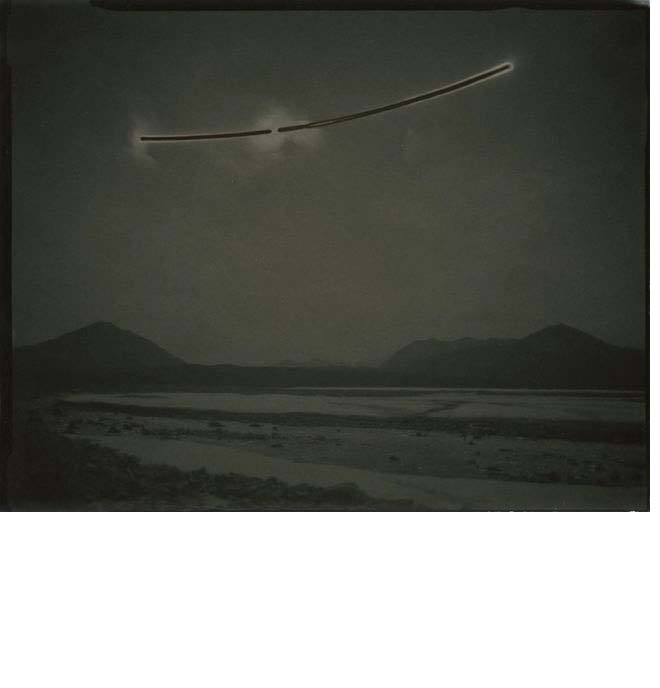

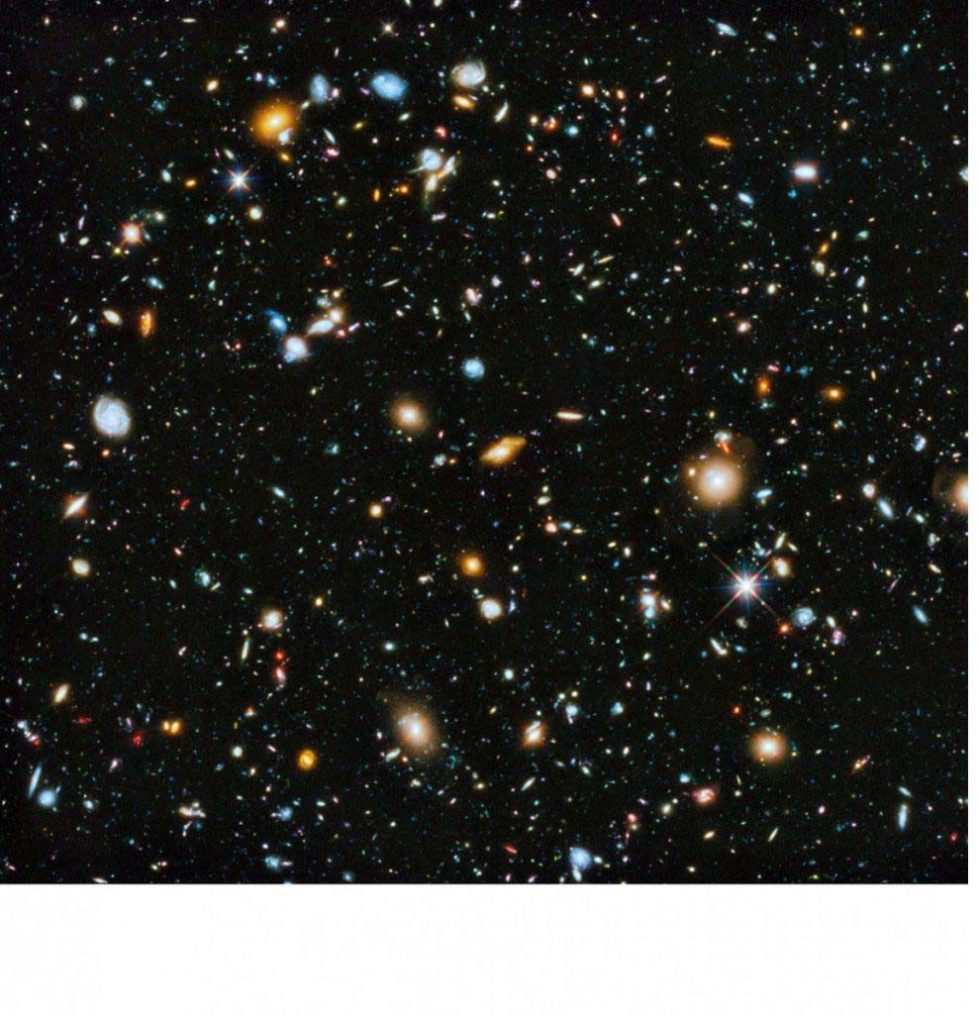

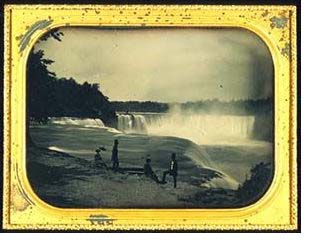

In the early days of photography, photographs were seen as an ideal means of conveying information about the wonders of the natural world, especially sublime places. Powerful, awe-inspiring, even frightening landscape features like Niagara Falls were sought out for their emotional charge and became popular destinations for tourists.

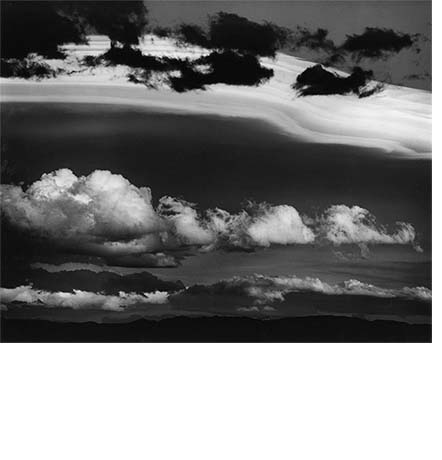

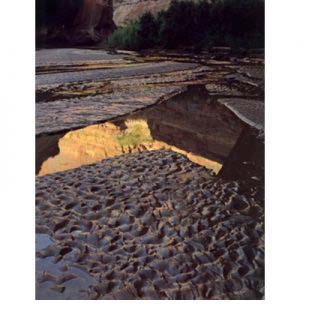

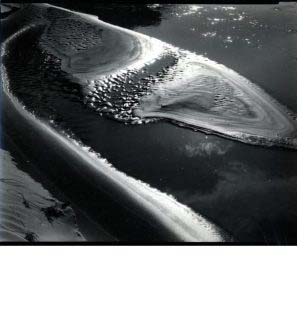

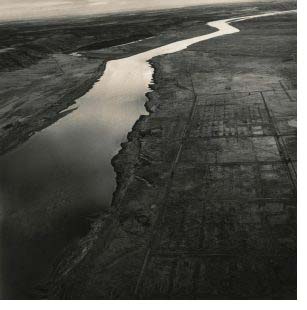

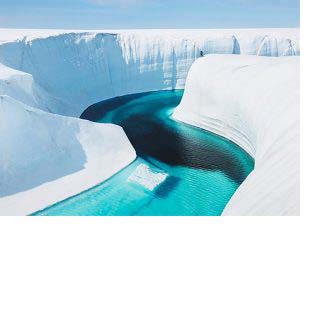

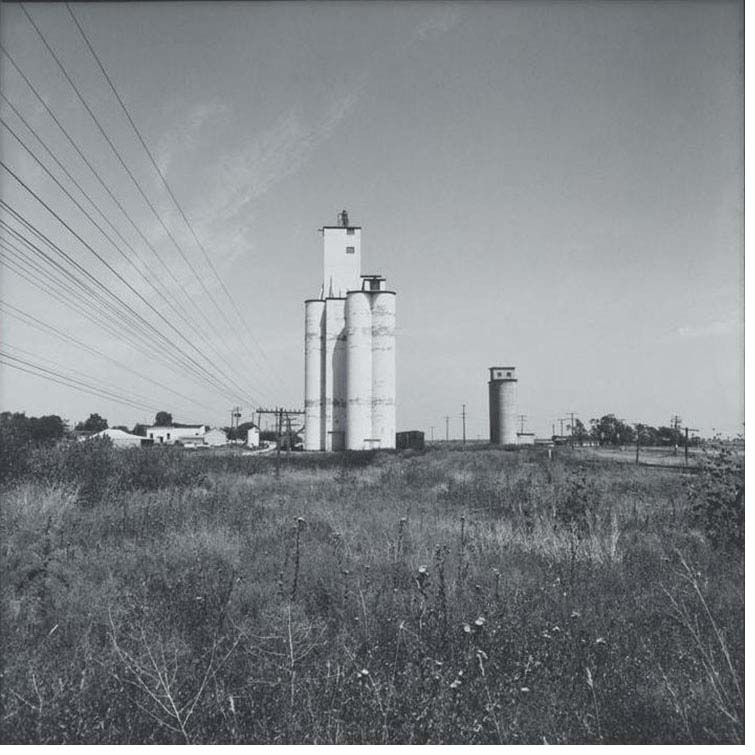

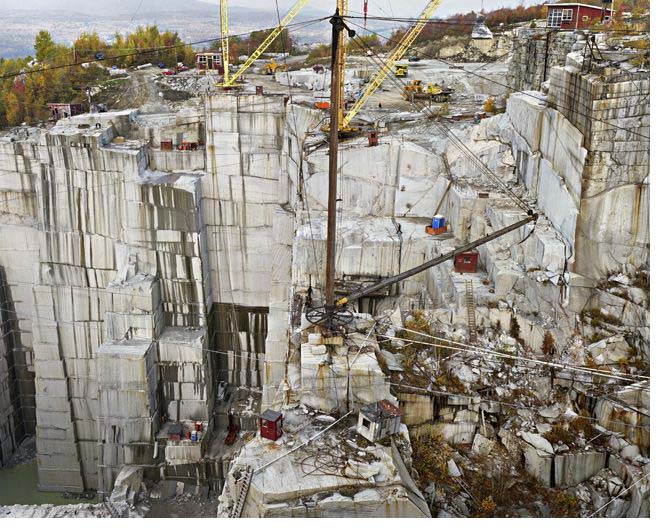

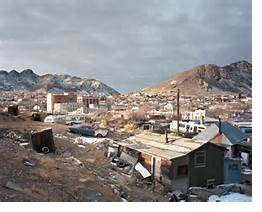

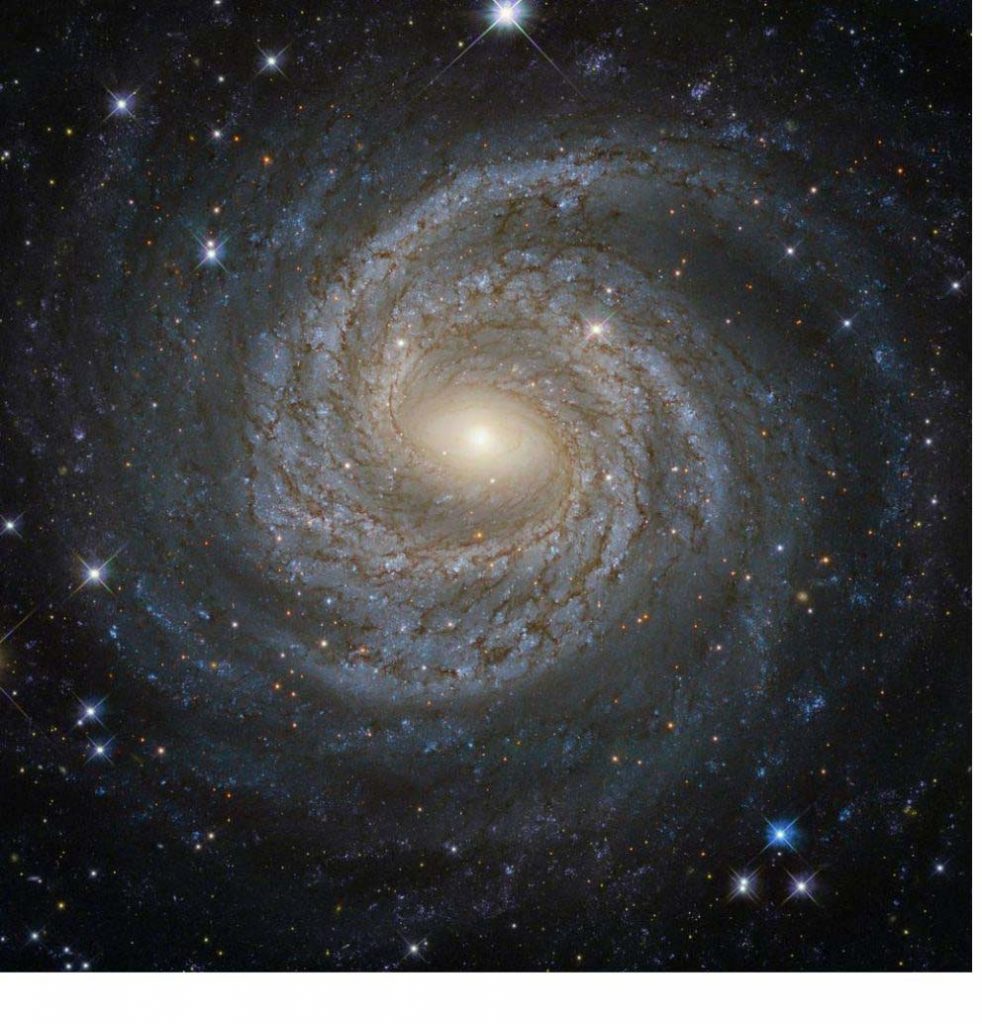

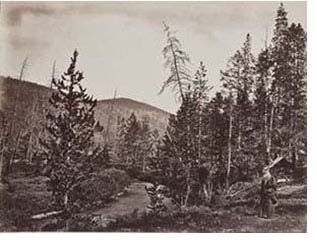

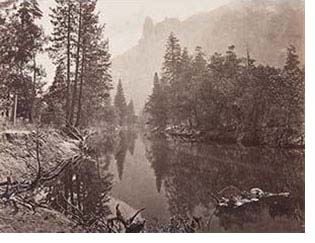

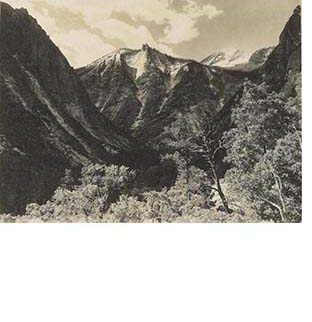

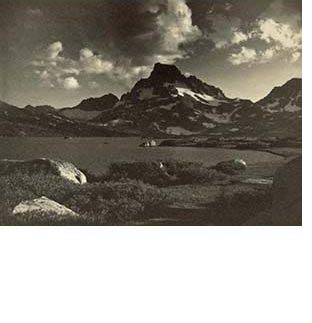

With accelerating industrialization and rapid urbanization, by the later nineteenth century the notion of untouched wilderness became increasingly appealing. Photographers presented the American West as a place apart, where humans played only minimal roles. Despite the growing presence of railroads, mines, boom-towns, reservations for Native Americans, and an Asian and Mexican immigrant workforce, the West was pictured in spiritual terms a place of transcendent beauty and geological spectacle.

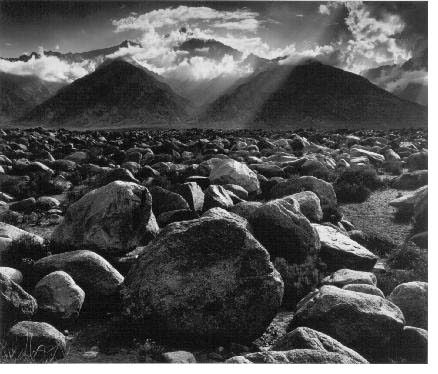

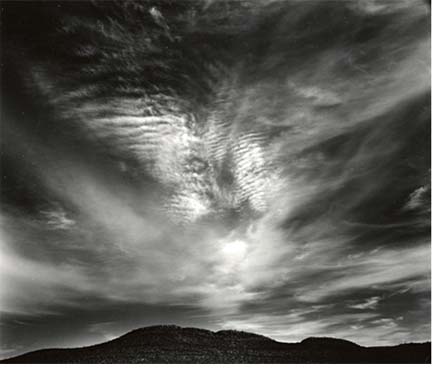

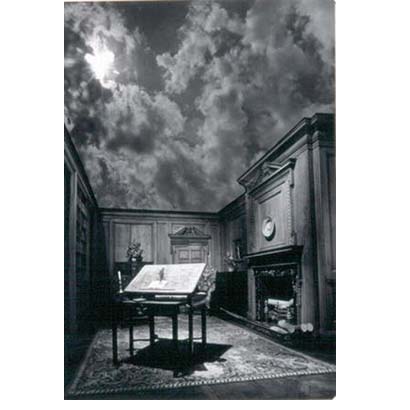

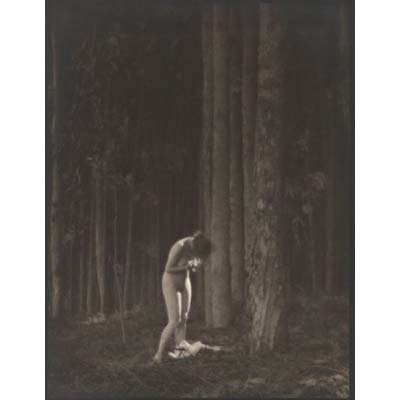

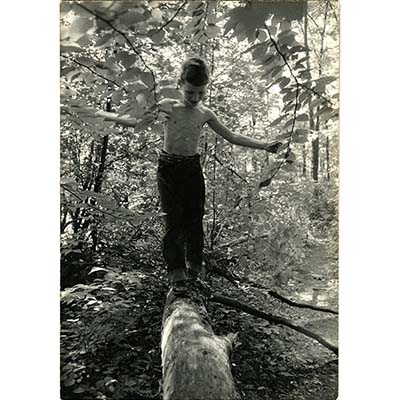

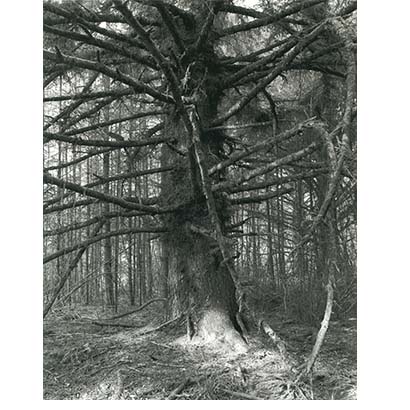

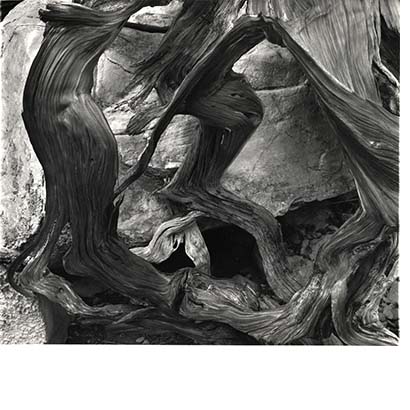

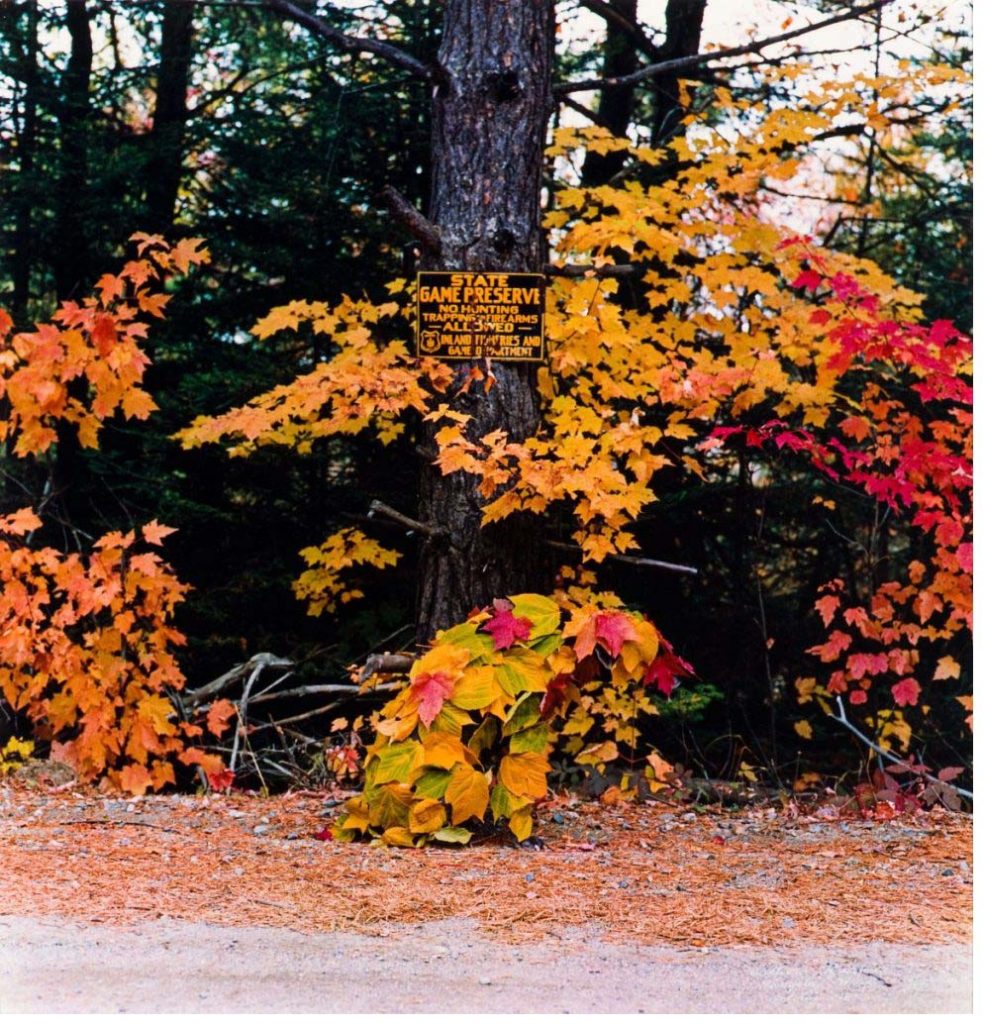

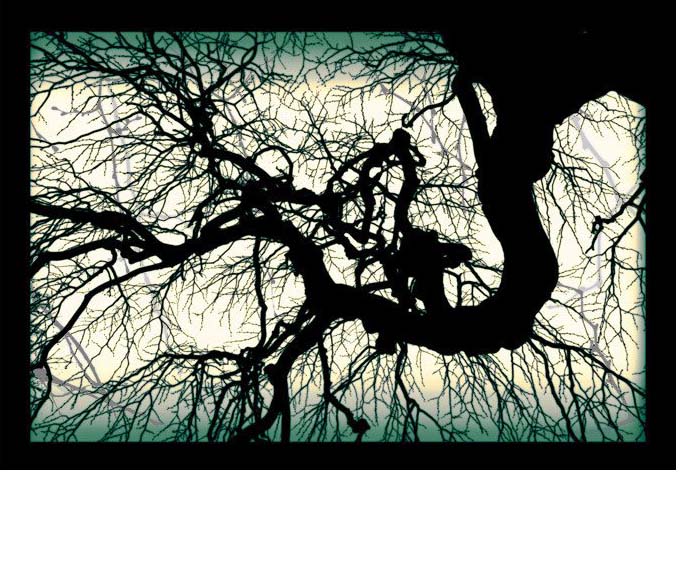

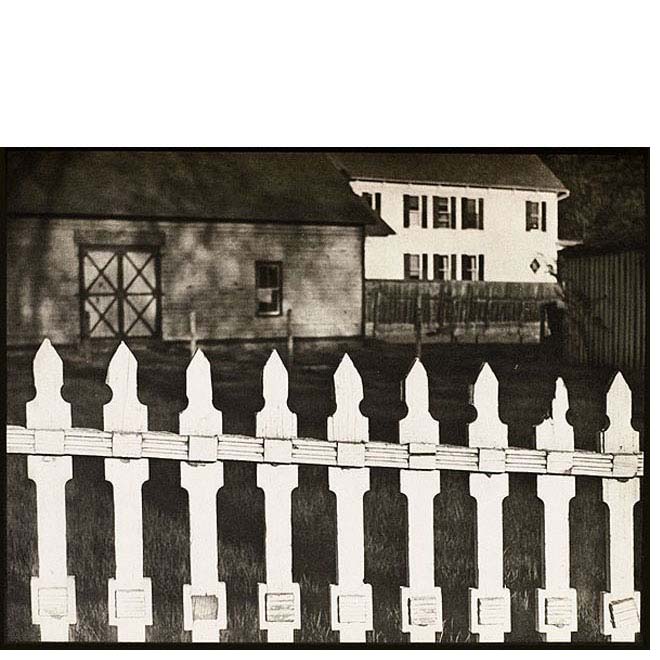

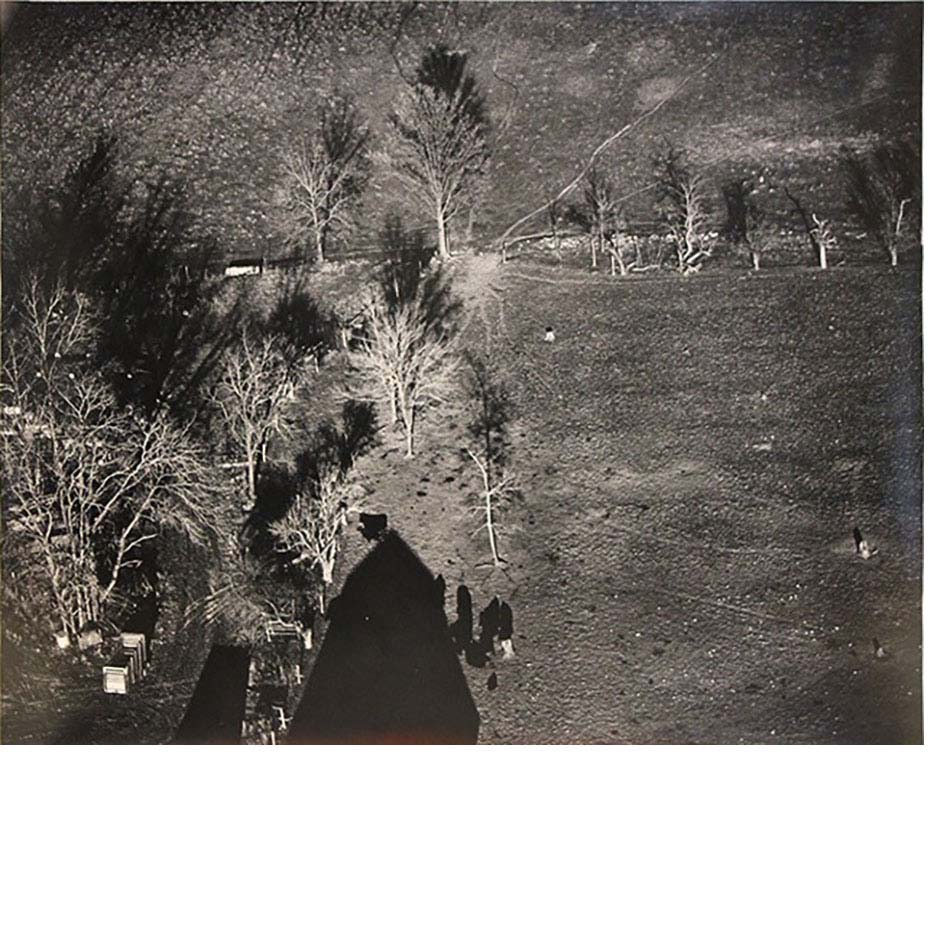

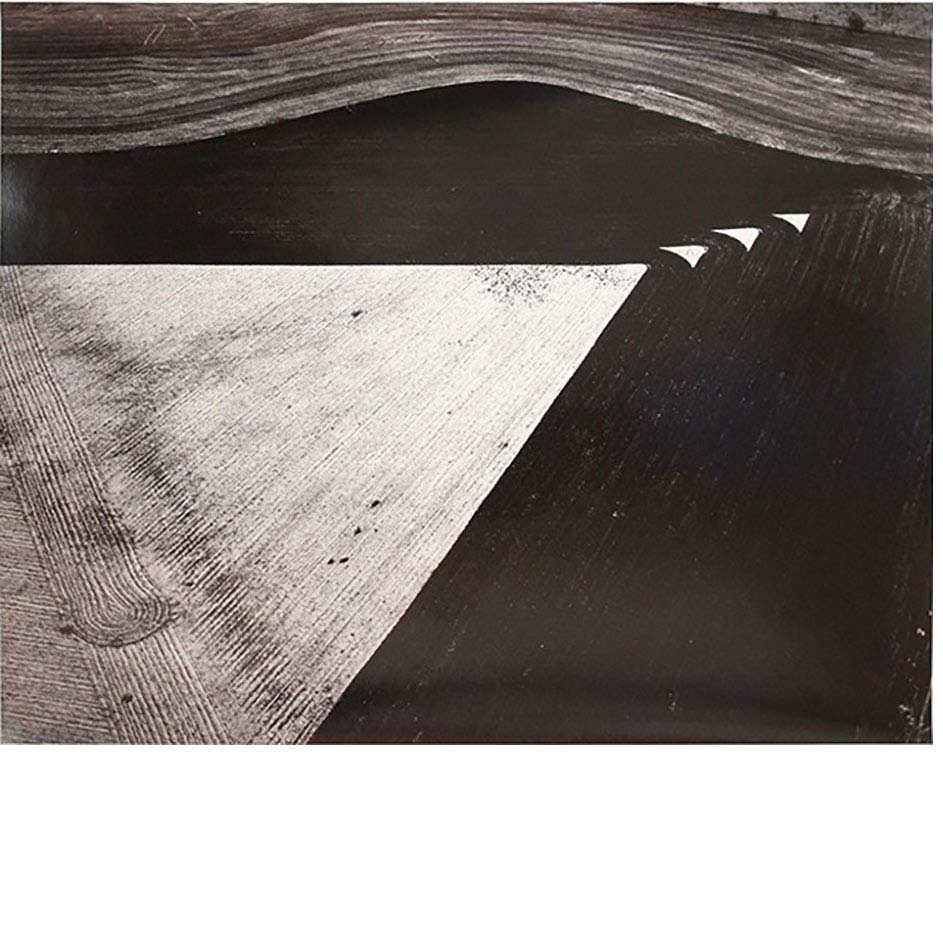

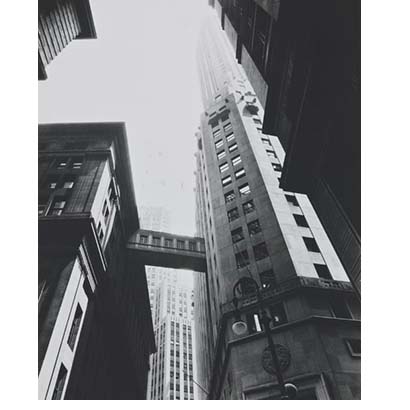

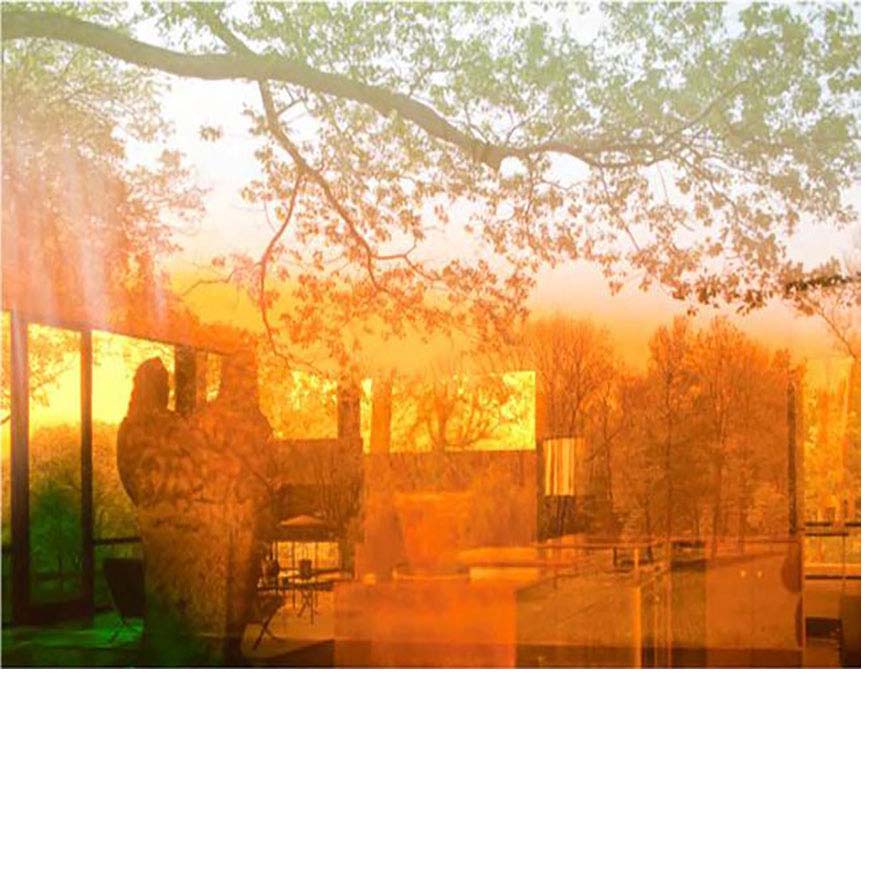

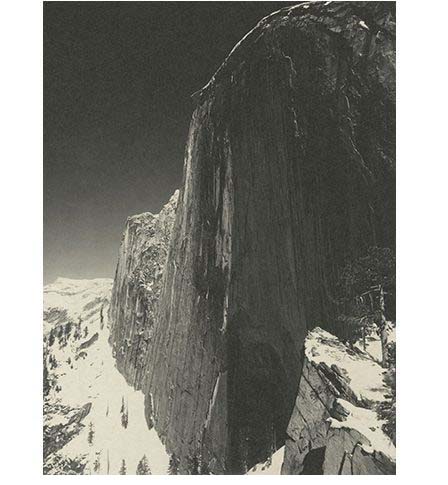

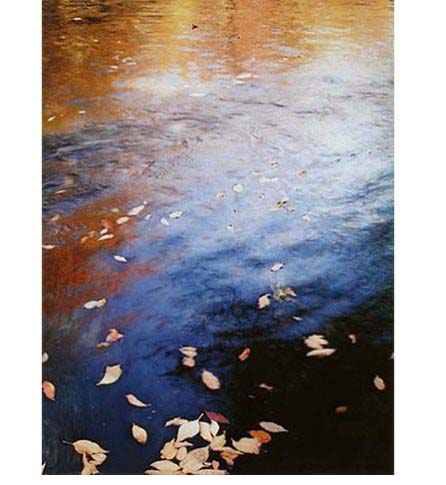

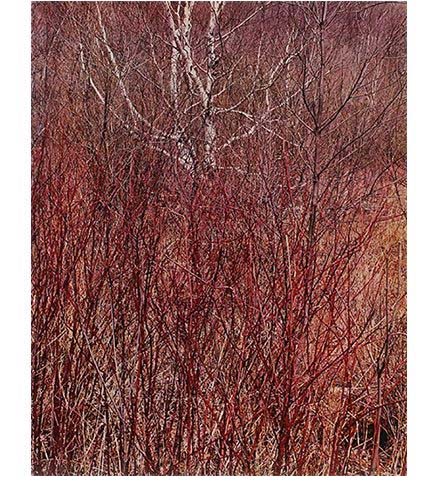

In 1892 the Sierra Club was founded in San Francisco, headed by wilderness writer, John Muir. Over the next century, the club would become a powerful force for wilderness preservation, especially through books featuring wilderness and nature photography. In his Sierra Club publications, Ansel Adams presented dramatic views of a seemingly untouched Western wilderness that would become the hallmark of his style. Taking a different approach, Eliot Porter focused on intimate views of nature, seen in the SIerra Club book, In Wildness is the Preservation of the World. Unlike Adams’ grand views, Porter’s photographs offered an immersive experience of nature, rather than admiring from afar. “Wildness” was a state of nature that could be found anywhere, especially in the New England woods.

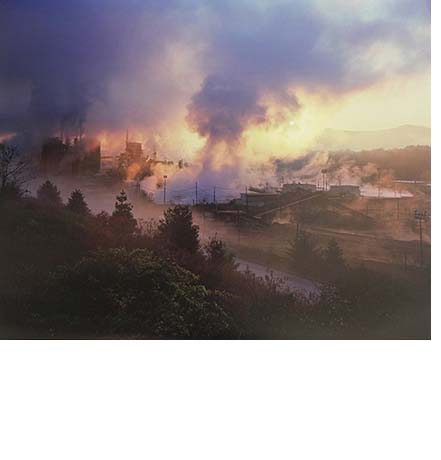

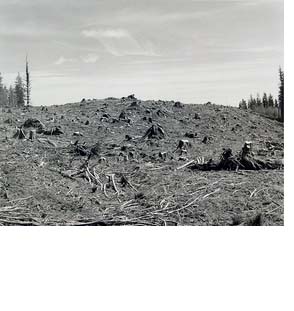

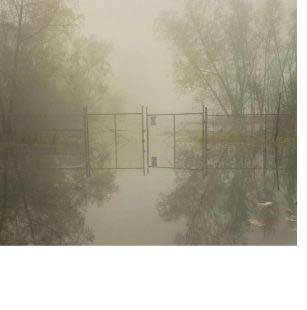

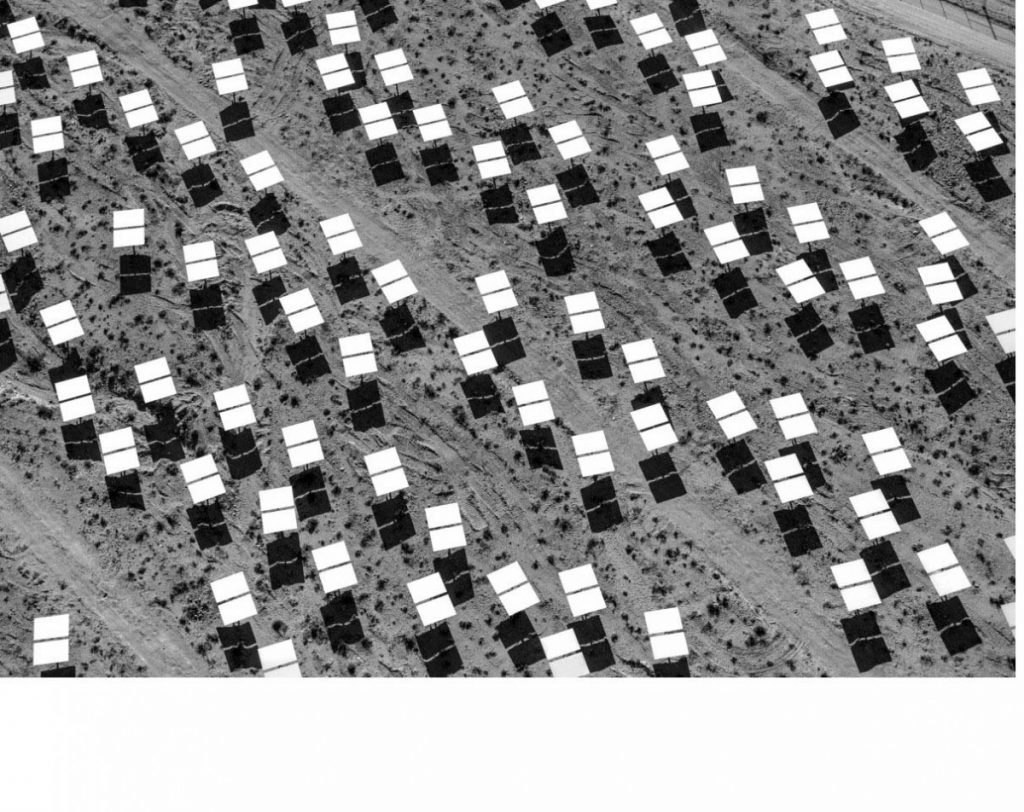

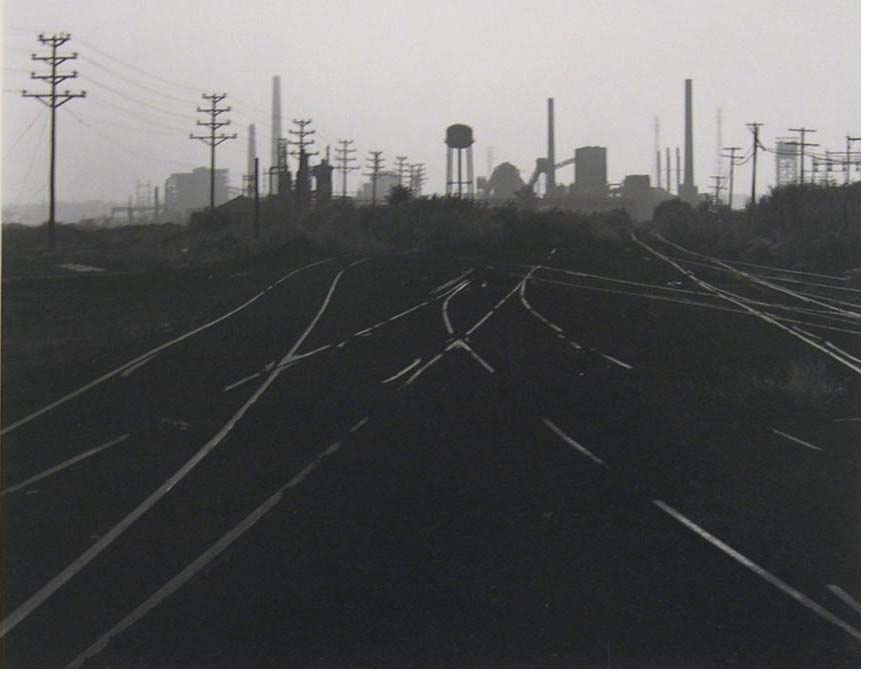

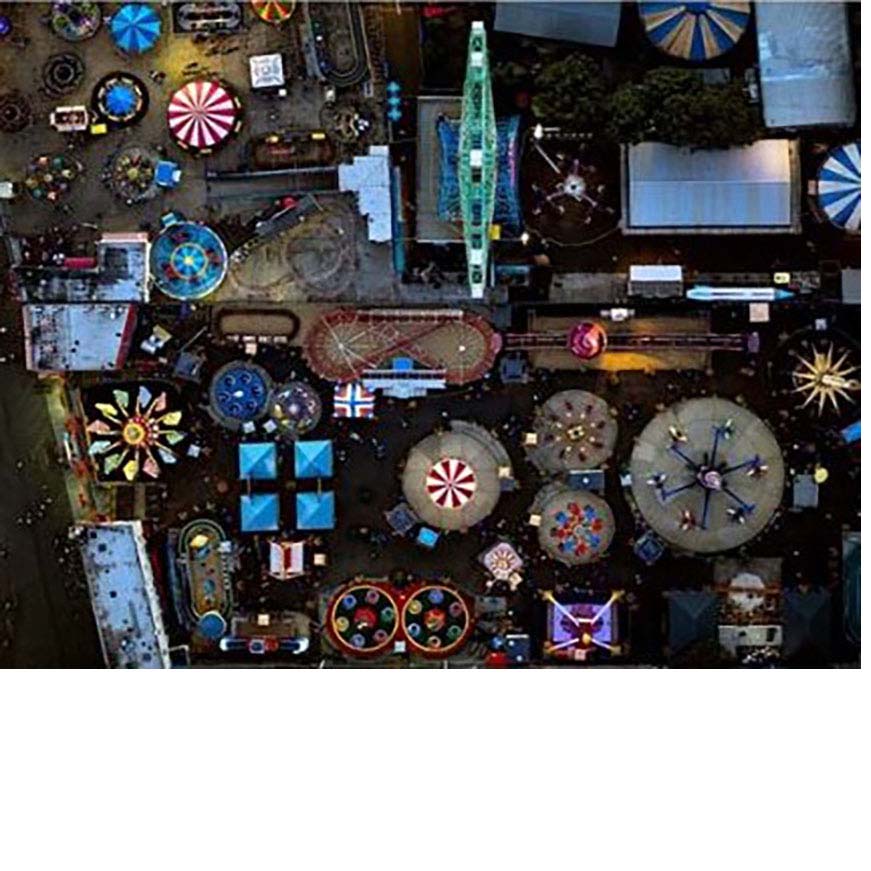

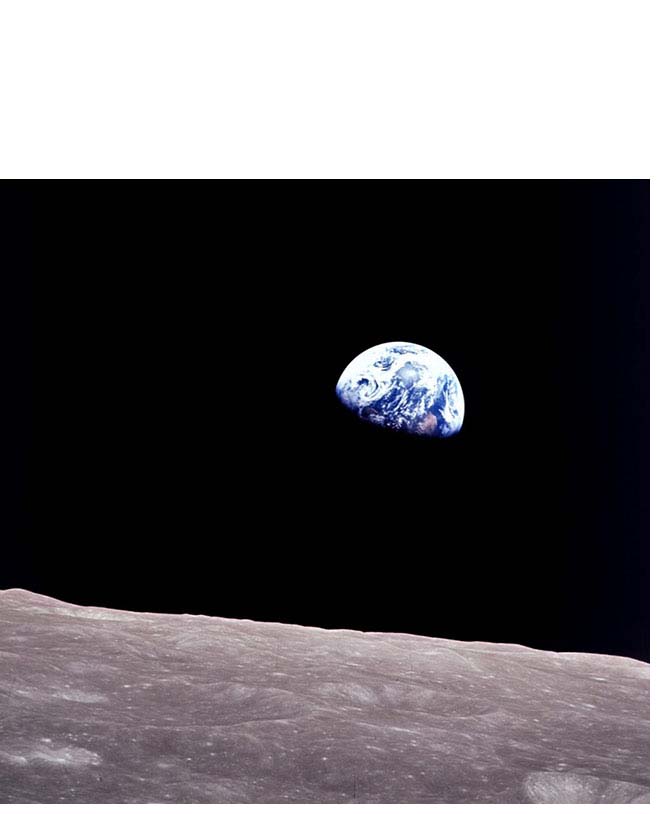

Regardless of whether a photographer pictured wilderness or wildness, the underlying premise was that the natural world should be appreciated on its own terms, apart from human intervention. This approach to nature and landscape would be challenged in the mid-1970s, as a younger generation of photographers called for non-idealized images that reflected the realities of land-use, suburban development, and environmental hazards.

Professor Christopher McGrory Klyza discusses the notion of wilderness: