![]() In 1943 and 1944, Ansel Adams made several trips from Yosemite to the Manzanar Relocation Center, located at the foot of Mount Williamson, where Japanese and Japanese-American citizens were interned after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Deeply distressed by the situation, Adams photographed the people and conditions, resulting in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, followed by a book, Born Free and Equal.

In 1943 and 1944, Ansel Adams made several trips from Yosemite to the Manzanar Relocation Center, located at the foot of Mount Williamson, where Japanese and Japanese-American citizens were interned after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Deeply distressed by the situation, Adams photographed the people and conditions, resulting in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, followed by a book, Born Free and Equal.

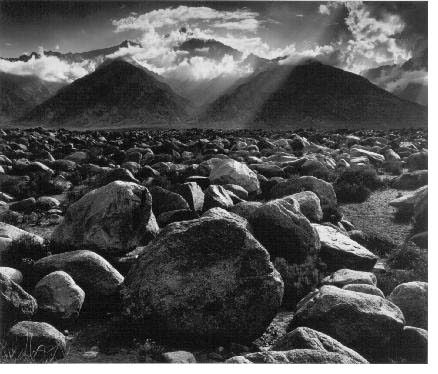

On one of the trips to the Manzanar camp, Adams made what he considered to be one of his best images, a view of a vast field of boulders with Mount Williamson in the distance surrounded by dramatic clouds. Adams firmly believed that the beautiful distant mountain range gave the internees a respite from their circumstances; however, one might also interpret the impassable field of huge boulders as a metaphor for their imprisonment.

Adams had visited this place several times, but the conditions had not been right for photographing Mount Williamson, whose dark granite rock tended to blend into the sky. He needed clouds to make the photograph work. He later commented, “When the clouds and storms appear the skies and the cloud-shadows on the mountain bring everything to life, shapes and planes appear that were hitherto unseen. Mountain configurations blend with and relate to those of the clouds. Paul Strand said to me at Taos, at my meeting with him in 1930 that was of such importance to my photography: ‘There is a certain valid moment for every cloud’.”[footnote]Ansel Adams, Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1983), p. 67.[/footnote]

Adams made the photograph using a large 8 x 10 view camera while standing on a rooftop platform on his station wagon. This elevated view enabled him to look over the boulders to the distant mountain range. He pointed the camera down and tilted the back to keep both the near rocks and the far mountains in sharp focus, setting up a composition with both near and far elements. He moved his car several times to position the camera for the composition he desired. Later in the darkroom, using the zone system he had developed to calculate tonal range, he skillfully exposed the photograph to hold detail in both the dark rocks and the brightly lit clouds in the final gelatin silver print.

![]() The town of Manzanar is located in the Owens Valley of eastern California. Adams was well aware of the environmental devastation that had befallen the region beginning in 1913, when Owens Lake and the streams that fed it from the mountains were diverted into an aqueduct to provide water for the city of Los Angeles. By 1926 the lake was almost entirely gone, creating an arid landscape from what was once a fertile valley. As Adams put it, “An American tragedy is here for all who care to see.”[footnote]Ansel Adams, Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1983), p. 163.[/footnote]

The town of Manzanar is located in the Owens Valley of eastern California. Adams was well aware of the environmental devastation that had befallen the region beginning in 1913, when Owens Lake and the streams that fed it from the mountains were diverted into an aqueduct to provide water for the city of Los Angeles. By 1926 the lake was almost entirely gone, creating an arid landscape from what was once a fertile valley. As Adams put it, “An American tragedy is here for all who care to see.”[footnote]Ansel Adams, Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1983), p. 163.[/footnote]

While the boulders that blanket the field in his photograph were first deposited long ago, the barren terrain offers a parallel to the destruction of the valley’s water supply. Photographer David Maisel’s The Lake Project, in the Troubled Waters section of the exhibition, presents an alternate view of the arid valley, which until recently was one of the highest sources of particulate matter pollution in the United States.

Watch and listen as geology professors Jeff Munroe and Pete Ryan answer the question: “How did those boulders get there?” Scroll further for a musical interpretation by Scott Waller, Middlebury Class of 2017.5.