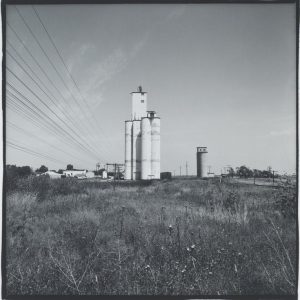

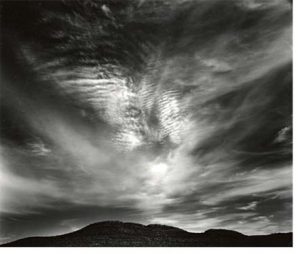

Wilderness Atmospheric Perspectives Troubled Waters Forest

Fenced and Farmed Built Environments Power Cosmos

Wilderness Atmospheric Perspectives Troubled Waters Forest

Fenced and Farmed Built Environments Power Cosmos

Click on a video below to listen to the piece:

Popularized by the Kodak Corporation in the 1940s, the dye transfer process enabled photographers to make full-color prints from film exposed in camera. From the original color film, three inter-negatives are exposed through red, green, and blue filters. From these separation negatives, gelatin reliefs capable of absorbing dyes in exact proportion to the densities of the negatives are made. The matrices are then dyed in the complementary colors, cyan, magenta, and yellow, and applied to the paper in exact register, along with highlight and shadow masks. The acid of the dyes migrate to the base of the paper, resulting in the final print.

Also called “dye coupler prints” and “type-C prints (if made from a negative) or “type-R prints (if made from a transparency),” chromogenic prints form the majority of color prints made after its introduction in 1936 and before advent of digital ink-based printing. The term “chrome” refers to the origin of the photograph in a slide or transparency. Some chromogenic prints produced today are made from scanned slides or transparency that are then printed digitally. Commercially manufactured paper coated with emulsions containing colored dyes, enabled photographers to choose form a wide range of surfaces, ranging form matte to ultra-glossy. Easier and less costly to produce than the dye-transfer process, some chromogenic prints lack the color stability of dye-transfer prints or archival digital papers and inks used today and are prone to color fading.

Digital photographs are images made from a digital file using a printer that applies very fine drops of ink on paper. Inks may be dye-based, however pigment-based inks have greater stability. The longevity rates of many pigment prints are calculated at over 100 years, depending on the paper used. As digital technology was developed in the early twentieth-first century, the question of print stability led to the development of increasingly stable inks and papers. Materials are subjected to rigorous accelerated again tests to determine how long a photographs will last without significant fading. Today there are many options of digital rag papers and inks that are expected to last more than a century, if prints are properly stored and exhibited.

The terms “Archival Pigment Print,” “Giclée Print,” “Digital Ink Print,” and “Inkjet Print” are sometimes used interchangeably for digital prints, however there are important distinctions between the stability of the types of inks used for prints.

Before the advent of digital technology at the end of the twentieth century, the gelatin silver process had been the most commonly used method of making black and white prints since the 1890s. A negative image is transferred to light-sensitive paper that has four layers: a paper base, a white opaque coating of gelatin and barium sulfate that creates a smooth surface, the gelatin layer that holds the silver grains of the photographic image, and a protective gelatin overcoat. Properly exposed gelatin silver prints are quite stable if exhibited under controlled light conditions.

Until the 1970s, art photographers used this process almost exclusively to create high-quality black and white prints. Color photography was considered a commercial medium, not suited to serious artistic expression. Today, as fewer and fewer photographers are working in darkrooms, gelatin silver printing is quickly becoming an antiquated, historic process.

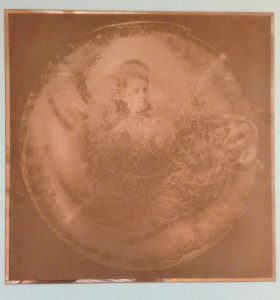

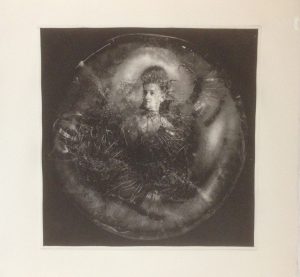

Photogravure is a photomechanical process that combines photography and etching to make ink-based photographic prints. A photograph is etched onto a copper place that is then inked. A dampened sheet of paper is placed on top of the inked plate, which is then run through an etching press. Popular with Pictorialist photographers who wanted to raise the status of photography to fine art at the end of the nineteenth century, in the early twentieth century photogravure was popularized by Alfred Stieglitz, who included finely made photogravures in his publication Camera Work. Unlike photomechanical processes such as half-tone that rely upon dot patterns to reproduce an image, photogravure produces a finely-nuanced continuous tone image. Color effects can be achieved through the use of tinted inks.

Stereography was an early form of three-dimensional photography. Two nearly identical images were placed side-by-side on cardboard. When viewed through a special viewer, the two images would merge into one with the illusion of three-dimensionality. Today this can also be achieved through animation, as seen in the video below.

Stereography was an early form of three-dimensional photography. Two nearly identical images were placed side-by-side on cardboard. When viewed through a special viewer, the two images would merge into one with the illusion of three-dimensionality. Today this can also be achieved through animation, as seen in the video below.

Stereographs became wildly popular during the second half of the nineteenth century. Affordable to everyone, they reached across class lines. By displaying views of far-away or inaccessible places, stereographs enabled viewers to learn about the world by imagining being there. Many nineteenth-century photographers who worked in the West produced large numbers of stereographs to support themselves, including Timothy O’Sullivan, Carleton Watkins, and Eadweard Muybridge.

Watch the accompanying video for a virtual stereograph viewer.

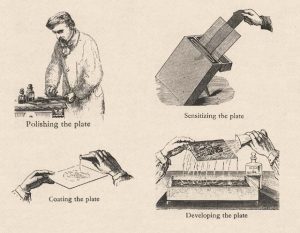

In 1851, Frederick Scott Archer invented a new photographic process to replace one-of-a-kind daguerreotypes on metal that were popular for portraits and multiple but imprecise calotypes made from paper negatives. The new process produced a clear negative on transparent glass that could be used to print multiple prints on paper. As its name implies,”wet-plate collodion” exposure and development of the negative had to be done within a ten-minute time frame while the light sensitive chemicals were wet, requiring photographers to bring portable darkrooms into the field. Although the process was capable of rendering fine detail within the shadows, the chemicals were sensitive only to blue light, making it impossible to render cloud-filled skies without exposing a separate negative only for the clouds. Because practical techniques for enlarging were not yet available, the glass negatives had to be the size of the finished print.

In 1851, Frederick Scott Archer invented a new photographic process to replace one-of-a-kind daguerreotypes on metal that were popular for portraits and multiple but imprecise calotypes made from paper negatives. The new process produced a clear negative on transparent glass that could be used to print multiple prints on paper. As its name implies,”wet-plate collodion” exposure and development of the negative had to be done within a ten-minute time frame while the light sensitive chemicals were wet, requiring photographers to bring portable darkrooms into the field. Although the process was capable of rendering fine detail within the shadows, the chemicals were sensitive only to blue light, making it impossible to render cloud-filled skies without exposing a separate negative only for the clouds. Because practical techniques for enlarging were not yet available, the glass negatives had to be the size of the finished print.

To achieve a large, or “mammoth,” print, a photographer required a glass negative of the same size, as well as a camera big enough to hold it. Thus photographing in places that were difficult to reach, like Yosemite Valley, meant hiking difficult terrain with mules loaded down with equipment, finding a source for water to rinse chemicals from plates, and a place to pitch a dark tent for working with poisonous and flammable materials. The sticky collodion solution would be carefully poured onto the clean glass, placed and exposed in the camera, developed in the dark, and finally fixed. Exposures required several seconds to several minutes, depending on the available light and the sensitivity of the chemicals.

Once a photographer had completed work in the field to obtain glass negatives, back in the studio prints were made using paper with light-sensitive materials suspended in a solution of albumen, or egg white. These prints would then be adhered to a thick cardboard mount to keep from curling. Popular during the second half of the nineteenth century, albumen prints were made on paper coated with a solution of albumen (egg white) and sensitized with silver nitrate.

Once a photographer had completed work in the field to obtain glass negatives, back in the studio prints were made using paper with light-sensitive materials suspended in a solution of albumen, or egg white. These prints would then be adhered to a thick cardboard mount to keep from curling. Popular during the second half of the nineteenth century, albumen prints were made on paper coated with a solution of albumen (egg white) and sensitized with silver nitrate.

Used primarily with wet-plate collodion negatives and for a short time with dry-plate negatives, albumen prints have a characteristic sepia tone. The dried egg white provided a protective coating that enabled stereographs to be handled without becoming scratched and larger prints to be mounted into albums for frequent viewing.