![]() In 2010, Jamey Stillings began photographing the construction and implementation of one of the largest solar projects in the world, the Ivanpah Solar Power Facility in the Mojave Desert. Rather than using photovoltaic solar panels, the Ivanpah project employs 173,500 heliostats, each with two mirrors the size of two garage doors. Arranged in concentric circles to follow the sun, the mirrors beam heat to four towers that use the heat to power steam turbines. Costing over two billion dollars, the project services an average of 140,000 homes per year.[footnote]Stephanie Heimann and Michelle Legro, “The Beauty of the World’s Largest Solar Project,” The New Republic, December 4, 2015.. https://newrepublic.com/article/124179/beauty-worlds-largest-solar-project. Accessed March 6, 2017.[/footnote]

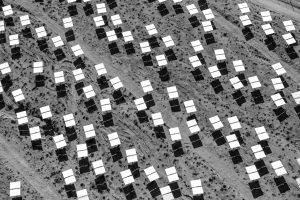

In 2010, Jamey Stillings began photographing the construction and implementation of one of the largest solar projects in the world, the Ivanpah Solar Power Facility in the Mojave Desert. Rather than using photovoltaic solar panels, the Ivanpah project employs 173,500 heliostats, each with two mirrors the size of two garage doors. Arranged in concentric circles to follow the sun, the mirrors beam heat to four towers that use the heat to power steam turbines. Costing over two billion dollars, the project services an average of 140,000 homes per year.[footnote]Stephanie Heimann and Michelle Legro, “The Beauty of the World’s Largest Solar Project,” The New Republic, December 4, 2015.. https://newrepublic.com/article/124179/beauty-worlds-largest-solar-project. Accessed March 6, 2017.[/footnote]

Stillings spent four years documenting Ivanpah. Flying over the facility, he captured the geometry of the mirrors, roads, and heating towers of the site. The photographer observes, “I’ve had a long-term interest in the intersection of nature and human activity. How we connect to nature; how we decide to use and modify nature for what we want to do.”[footnote]Quoted in Olivier Laurent, “See the World’s Largest Solar Plants From Above,” Time, February 26, 2015. http://time.com/3722444/worlds-largest-solar-plants-photographs/. Accessed March 6, 2017.[/footnote]

Like Marilyn Bridges before him, Stillings has found that aerial views emphasize the graphic geometries of the massive sites he photographs: “In our inexorable quest for energy to meet the growing demands of a consumption dependent culture, we are transforming our natural, rural, and urban landscapes at an accelerating pace. The need to examine such transformations with an aesthetic and critical eye is compelling and necessary. To think consciously about the decisions we make, or have imposed upon us, we need to see these changes. As an artist, aerial photography is a principal component of my work. I explore perspectives distinct from those found on earth’s surface, revealing information and insight otherwise concealed.”[footnote]Quoted in Aline Smithson, “Jamey Stillings: Changing Perspectives: The Evolution of Ivanpah Solar,” Lenscratch, March 19, 2014. http://lenscratch.com/2014/03/jamey-stillings-2/. Accessed March 6, 2017.[/footnote]

Ivanpah Solar has been criticized for its negative ecological impacts: birds have been burned when flying into the solar beams or killed by crashing into the mirrors. The desert tortoise population had to be relocated. Stillings counters, “When a blogger uses terms like ‘…the ecological disaster that is Ivanpah Solar,’ I say, ‘Look, when you use this terminology applied to renewable energy, I get that you’re upset about the use of the desert land, I get that you’re upset about the desert tortoise and I understand why. But when you use terminology like this, you leave no stronger verbiage for the BP oil spill, the Alberta Tar Sands mining or the Fukushima disaster. So, let’s find a place where we can talk, where we can realize that the answers are never black and white. There are always shades of gray. Let’s find a way to move forward constructively by talking and making responsible decisions.’ “[footnote]Quoted in Jamie Leo and Robin Madel, “Photographer Jamey Stillings: Seeing the Big (Solar) Pictures,” EcoCentric, March 15, 2013. http://www.gracelinks.org/blog/2195/photographer-jamey-stillings-seeing-the-big-solar-picture. Accessed March 6, 2017.[/footnote]