Corporations, Like Soylent Green, Are People

For many, the 2010 decision of the Supreme Court in Citizens United v. FEC (PDF) seemed like a further step in the reification of corporations. Briefly, the decision held that it was unconstitutional to restrict the political speech of corporations (read: spending on political campaigns), as doing so violated the First Amendment rights of persons within the United States – the underlying assertion is that corporations are legal persons. Critics pointed out that the norm of corporate personhood – giving corporate entities legal rights equivalent to those of ordinary citizens – would likely mean the concentration of political power in the hands of corporate CEOs and the wealthy. Well, it turns out that, in addition to empowering them, the norm of corporate personhood may be used to hold corporations accountable for their actions.

Background: Environmental Injustice and Shell in Nigeria

In the 1990s, oil exploration in Nigeria was a travesty of environmental injustice. In the Nigerian Delta, the practice of extraction was incredibly dirty – oil spills, and gas flaring devastated the local environment, and displaced residents. Moreover, the federal government of Nigeria monopolized the control of national oil wealth, giving a disproportionately low share to the residents of states in which oil exploration was taking place.

In the 1990s, oil exploration in Nigeria was a travesty of environmental injustice. In the Nigerian Delta, the practice of extraction was incredibly dirty – oil spills, and gas flaring devastated the local environment, and displaced residents. Moreover, the federal government of Nigeria monopolized the control of national oil wealth, giving a disproportionately low share to the residents of states in which oil exploration was taking place.

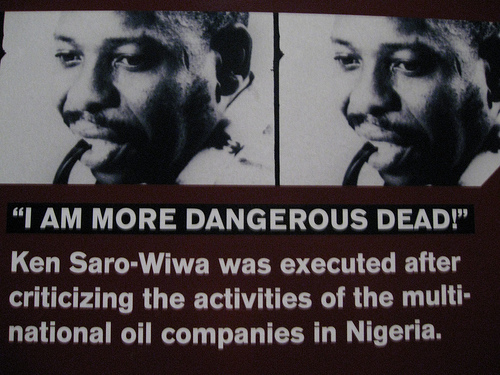

To make matters worse, Shell, seeking to maintain oil extraction, facilitated the displacement and murder of residents of the Delta region, largely of the Ogoni tribe. As indicated in this book excerpt (PDF), Shell contractors bulldozed farmland and houses in order to gain access to oil-producing land. When people protested, they were shot by the Nigerian army. When they protested those shootings, they were shot. When they blocked the community to further oil exploration, the Nigerian army and police went to ‘dialogue’ with the community, and they were shot. In these instances, army and police officers were paid field allowances by Shell, who later wrote to “reiterate our appreciation for the excellent co-operation we have received from the Nigerian Police Force in helping to preserve the security of our operations.” This pattern continued until several people were killed, including Ken Saro-Wiwa, poet, author, television personality, and environmental activist.

Hold Them Accountable

In response, a transnational coalition of Ogoni people and American legal advocacy agencies sued Shell, starting in the 1990s, for complicity in these atrocities. Here’s the kicker: they cited a two centuries old law, the Alien Tort Statute (ATS), which allows aliens to sue in federal district courts for “…a tort only, committed in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States.” A decade and a half later, the case seemed to stall, when the Second Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed the charges, asserting in a majority opinion that, despite the clear violation of human rights law, and despite the seriousness of the claims, corporations could not be considered “juridical persons (PDF)” when it became time to hold them accountable for their actions.

However, on October 16th, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case on appeal. At the heart of it, this case raises the question of whether corporations can have the rights of citizens without their corresponding responsibilities. Obviously, the most optimistic outcome, and one which we will find out next year after the case is concluded, is that the SCOTUS finds that corporations are, in fact, liable for human rights violations – that at least would indicate some conceptual consistency among the conservative branch. If, however, they find that Shell is not liable, as non-juridical persons under international law, it may expose the hypocrisy and emptiness at the core of the idea of corporate rights.