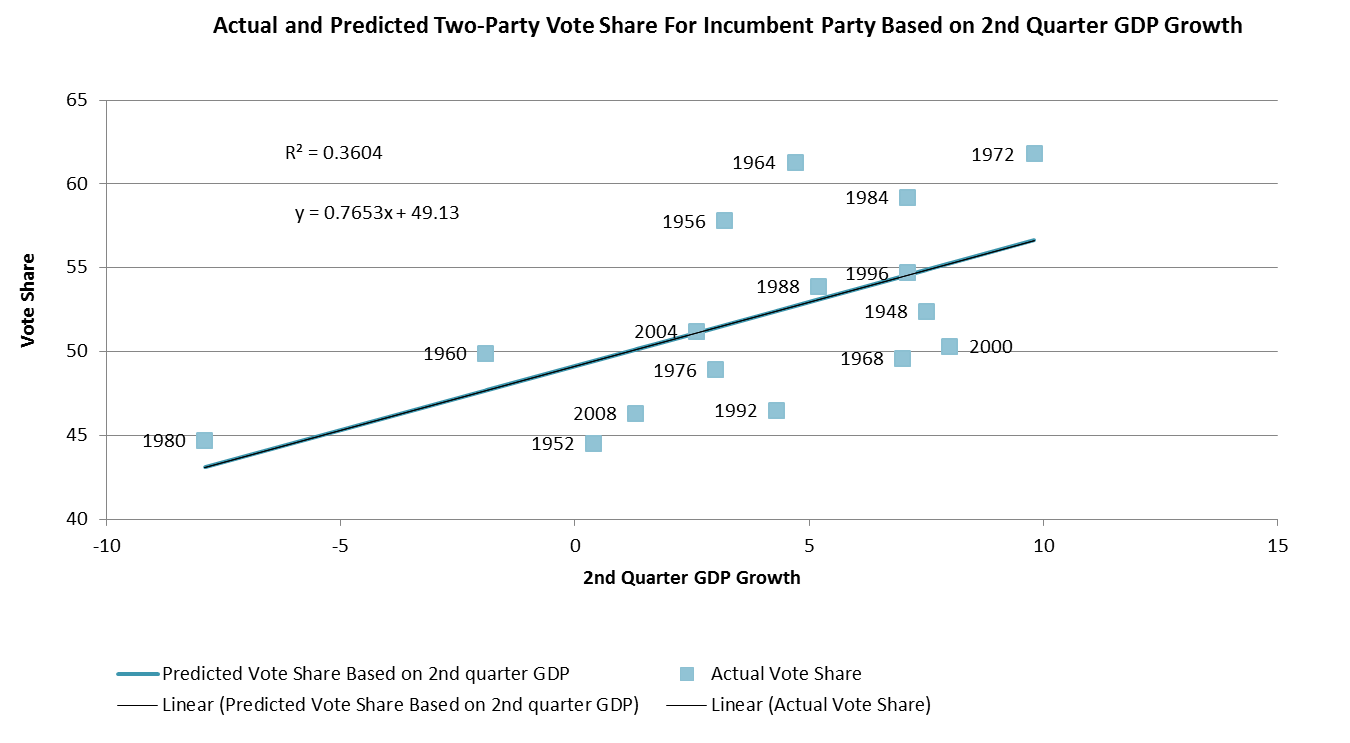

I want to pick up a discussion I began in this post at the Economist’s Democracy in America site regarding political science election forecast models. At this point in the presidential race, less than 100 days before the election, some of the fundamentals that political scientists incorporate into these econometric models are set, and we are going to see more of their predictions come out in the next several weeks. As I noted in the earlier post, with the release of the 2nd quarter GDP figures last Friday, all the pieces are in place for Emory political scientist Alan Abramowitz to issue his “Time for A Change” forecast. It predicts that Obama will receive 50.5% of the major party vote in November, making him a very slight favorite to retain the presidency. But as I discussed, Abramowitz has tweaked his forecast model, adding a “polarization” variable that he describes as follows: “For elections since 1996, the polarization variable takes on the value 1 when there is a first-term incumbent running or when the incumbent president has a net approval rating of greater than zero; it takes on the value -1 when there is not a first-term incumbent running and the incumbent president has a net approval rating of less than zero.”

Based on this description, the polarization variable will come into effect in 2012, since Obama is a first-term incumbent. This matters, because the addition of the polarization variable reduces Obama’s projected vote share by more than 2%. That is, under the “traditional” pre-polarization Abramowitz model, if I’ve done my calculations correctly, his forecast would have Obama winning 52.7% of the major party vote – a more comfortable margin! However, as Abramowitz explains, his traditional model had overstated the winning candidate’s margin of victory in the last four elections. The reason, he argues, is an increasingly polarized electorate that is less likely to cross party lines to vote for the other party’s candidate even when the “fundamentals” suggest they should. The polarization variable brings his predictions more in line with the actual results of the last four elections.

But is the variable justified, or is it simply an ad hoc retrofit that has no substantive basis? In previous posts I have argued that there is little evidence that the public has become more polarized in recent years, even as political elites have grown increasingly partisan. Abramowitz, however, disagrees. As he and his co-author Kyle Saunders write in this article “The argument that polarization in America is almost entirely an elite phenomenon appears to be contradicted by a large body of research by political scientists on recent trends in American public opinion.” Moreover, they argue that this increase in polarization tends to make citizens more engaged in politics – not less. As evidence, they point to National Election Studies (NES) data that show a steady increase, from about 50% in 1952 to about 75% in 2004, in the number of Americans who perceive a strong difference between the two parties. There was a similar increase, from just under 70% to well over 80% during this time span in the number of Americans who care who wins the presidential election. This is evidence, Abramowitz argues, that voters are increasingly polarized, and he uses it to justify tweaking his traditional model.

The problem with the Abramowitz/Saunders’ claim of a more polarized America, as Mo Fiorina has pointed out, is that it confuses a polarization in voter choices with polarization among voters themselves. Thus, we should not be surprised that an increasing number of Americans perceive a difference between the parties. There is a difference, but it reflects a process of party sorting – not a growth in ideological extremism. Simply put, party labels have become increasingly aligned with partisan ideology; there are fewer conservative Democrats or liberal Republicans today. So quite naturally more people perceive a difference between the parties today than they did a half-century ago – but this does not mean the public is more polarized along partisan lines.

Similarly, if the choices for president are viewed as more ideologically extreme, it makes sense that more voters are going to express an interest in who wins. Indeed, one reason voter turnout was so high in 2004 and again in 2008 is that that many voters viewed the candidates as espousing ideologically distinct views on the major issues. In 2004, as Abramowitz’s own data shows, George W. Bush was a very polarizing figure. It is therefore no great surprise that a record number of voters cared who won the presidential election that year, and that turnout was up. A similar argument can be made about the 2008 presidential race.

So, if the American public is not increasingly polarized, contrary to Abramowitz’s claims, does that invalidate his inclusion of a polarization variable in his forecast model for the post-1992 presidential elections? Is Obama more likely to get 52.7% of the popular vote rather than 50.5%? Not necessarily. Abramowitz’ explanation may be faulty, but the polarization variable may still work if more voters are viewing their choices in the presidential election in polarized terms. Even if this is true, however, I’d like to see more evidence suggesting that the public’s perception of the ideological differences between the presidential candidates grew significantly higher in 1996, and has remained higher ever since, as Abramowitz’s new forecast model suggests. Moreover, I’m not sure this is leading an increasing number of voters to cast ballots contrary to what the fundamentals would indicate – it may be instead that they see the two candidates’ issue stances regarding the fundamentals as distinctly different. Thus, in 2012, Romney and Obama are espousing two very distinct views for addressing the lingering effects of the Great Recession. Many moderate voters may not buy entirely into either view but they don’t have the luxury of mixing and matching elements from both candidates’ programs. Instead, they must choose – even if they don’t necessarily fully embrace either choice.