The much awaited second quarter GDP growth figure came out yesterday and, while it wasn’t a disaster, neither was it particularly good sign for the economy – or for President Obama’s reelection chances. The government’s first estimate (they often revise the figure as new data comes in) is that GDP grew at an anemic 1.5% – a .5% drop from first quarter growth, and only half of the growth rate experienced during the last quarter of 2011. This downward trend line is not what an incumbent president wants to see heading into an election.

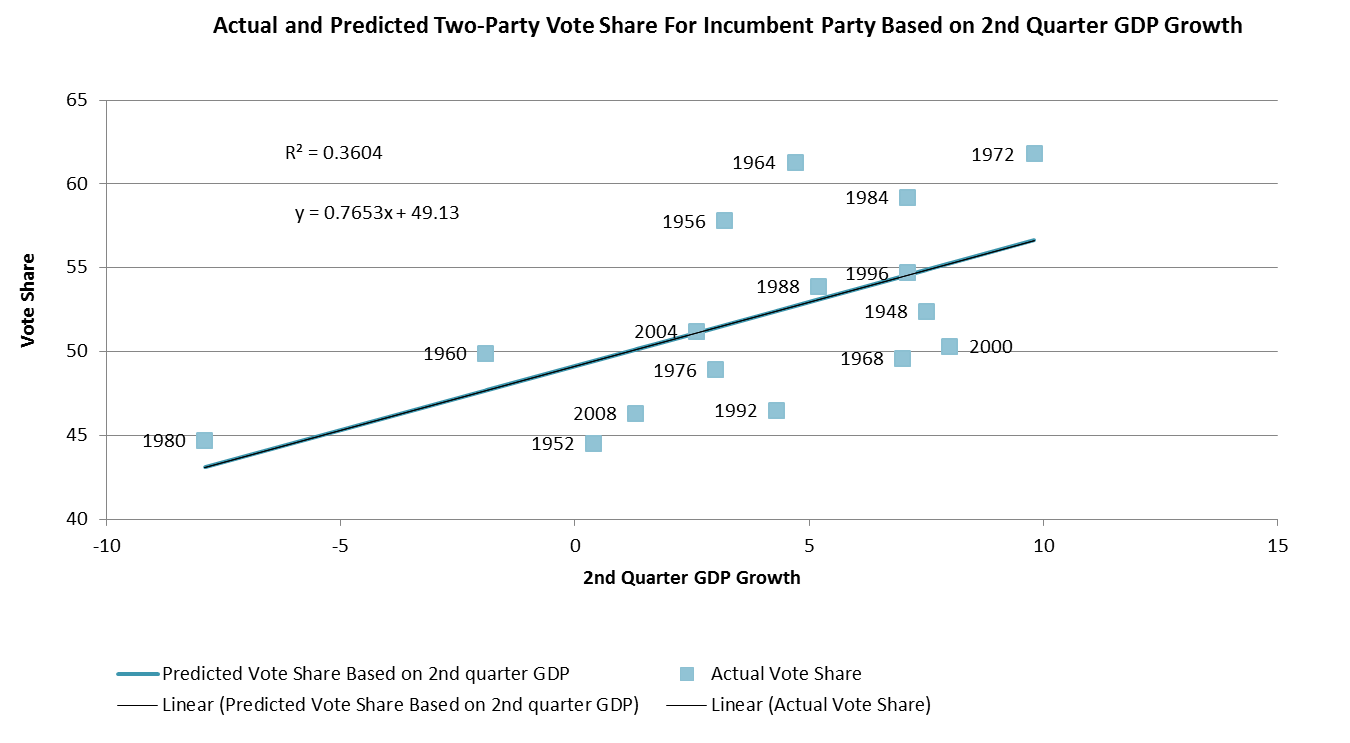

As you know from reading my previous posts, GDP growth is one way of measuring one of the key “fundamentals” – the state of the economy – that I have been arguing is far more important to the election outcome than the Bain controversy or Obama’s verbal “gaffes”. But it isn’t the only factor influencing the election, and so we shouldn’t overstate its significance either. Peter Cahill has gathered data on second quarter GDP growth in every election year dating back to 1948, and correlated it with the actual share of the major-party vote won by the incumbent presidential party’s candidate.

Think of the trend line as the “real” linear relationship between GDP growth and vote share. If we plug 1.5% into the equation defining that line, it predicts that Obama will get about 50.3% of the two-party vote come November based on 2nd quarter GDP growth alone. However, as you can see from the graph, while higher GDP growth generally correlates with a greater vote share, the relationship is not perfect; GDP growth only explains about 36% of the variation in vote share. So a lot of other factors are going to come into play. What are they? As I discussed in yesterday’s post for the Economist’s DIA blog, Emory political scientist Alan Abramowitz’ “Time for A Change” forecast model adds three additional variables to second quarter GDP growth: the incumbent’s net approval (approval minus disapproval) in the Gallup poll at the end of June, how long the incumbent’s party has held the presidency and – in a recent innovation – a “polarization” term that takes into account the increased polarization of the electorate since 1996. With yesterday’s GDP release, all the figures are in place for Abramowitz to predict Obama’s share of the major party vote come November.

Think of the trend line as the “real” linear relationship between GDP growth and vote share. If we plug 1.5% into the equation defining that line, it predicts that Obama will get about 50.3% of the two-party vote come November based on 2nd quarter GDP growth alone. However, as you can see from the graph, while higher GDP growth generally correlates with a greater vote share, the relationship is not perfect; GDP growth only explains about 36% of the variation in vote share. So a lot of other factors are going to come into play. What are they? As I discussed in yesterday’s post for the Economist’s DIA blog, Emory political scientist Alan Abramowitz’ “Time for A Change” forecast model adds three additional variables to second quarter GDP growth: the incumbent’s net approval (approval minus disapproval) in the Gallup poll at the end of June, how long the incumbent’s party has held the presidency and – in a recent innovation – a “polarization” term that takes into account the increased polarization of the electorate since 1996. With yesterday’s GDP release, all the figures are in place for Abramowitz to predict Obama’s share of the major party vote come November.

Drum roll please!

By plugging the relevant numbers into the Abramowitz forecast equation, it spits out Obama’s predicted share of the major party vote come November as 50.5% – not much different from our estimate based only on second-quarter GDP growth. Based on the confidence interval around this prediction, Abramowitz estimates that if history holds Obama has about a two-thirds probability of winning the election.

This is an estimate, mind you, based on data from a small number (16!) of previous presidential elections. But I would argue that it is better than a guess – Abramowitz’s model has performed generally quite well in out-of-sample forecasts, coming within 1.5% of the actual vote about three-quarters of the time. On the other hand, I wouldn’t bet my kid’s tuition, based on this one model, that Obama will be victorious. In short, it is telling us what pretty much every other indicator suggests: that this is going to be a very, very close election but that Obama can be considered a very slight favorite.

So, does this mean the outcome is already in the bag, and that what happens from here on out doesn’t matter. Not at all. Campaigns do matter – see my previous posts here and here. And in terms of consequences, in such a close election, they arguably matter even more this time around.

Abramowitz’s model, of course, is only one of several constructed by political scientists and, as I discussed in my Economist post, his recent change to his model is not sitting well with everyone. (I’ll discuss this in a separate post.) By my count, there were more than a dozen econometric-based forecast models in 2008. Although they were all, save one, able to predict Obama’s victory, they weren’t equally reliable in forecasting the actual popular vote (although they did pretty well in the aggregate). And, of course, as we get closer to the actual election, none of them will be as reliable as simply aggregating the public opinion polls, which is what Sam Wang, Nate Silver and others will end up doing. So why discuss them at all? Because the best ones remind us that there is a context to this election which largely determines how it will turn out. And right now that context is saying that this election may be too close to call.