Steve Lombardo, a former Romney adviser in 2008, writes this in his Huffington Post column today: “Any serious observer of the presidential election has to be scratching his/her head. In mid-September Obama was on track for reelection because Romney, at that point, had been deemed unacceptable by a vast segment of the electorate. Now, in mid-October, the President is dazed, staggered by a near knockout in the first debate and a subsequent Romney surge that seems to have the Governor on a winning trajectory. The problem is that neither scenario accounts for unplanned events.”

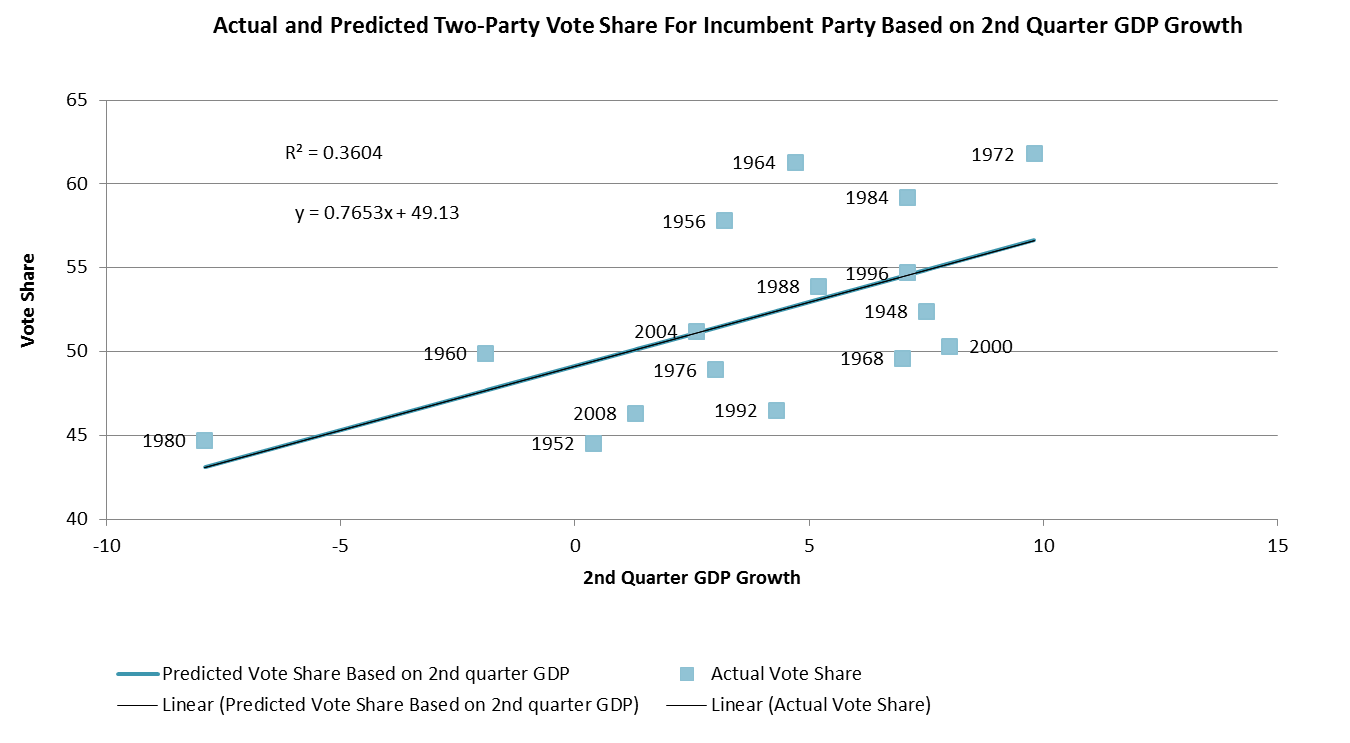

Except that’s not true. This race is essentially tied not because of “unplanned events”, but because of perfectly predictable events; as we get closer to Election Day, more and more voters are behaving almost exactly as political science forecast models suggested they would. As I said again and again, although Obama was outperforming the economic fundamentals in many of the swing state polls during September, that did not mean that this election was not going to tighten as more voters begin tuning into the race.

But pundits persist in insisting that rather than responding rationally to the state of the economy, voters are instead a fickle bunch who are largely ignoring the economy. Consider this observation today by another pundit who, citing a Gallup poll titled “U.S. Economic Confidence Best Since May, tweeted this: “I give up trying to make sense of this election.” Evidently he doesn’t understand how the race could be tied if voters’ economic confidence is on the rise. Again, however, if you look at the actual poll, (and not just the title), it’s pretty clear why Romney and Obama are running neck-and-neck.

The reality is that despite the positive trend recently in voters’ economic outlook, the poll actually shows that more Americans continue to be pessimistic about the state of the economy. Their collective confidence may be the best since May – but that’s not saying a helluva lot. And that pessimism is largely driving today’s polling numbers. Gallup’s Economic Confidence Index is based on the combined responses to two questions, the first asking Americans to rate economic conditions in this country today, and second, whether they think economic conditions in the country as a whole are getting better or getting worse. The Index is then computed by adding the percentage of Americans rating current economic conditions ((“excellent” + “good”) minus “poor”) to the percentage saying the economy is (“getting better” minus “getting worse”), and then dividing that sum by 2. So, an index above zero indicates that more Americans have a positive than a negative view of the economy; values below zero indicate net-negative views. As you can see, the index is still strongly negative. So, is it surprising that as Americans increasingly tune into the election to consider which candidate they will support that Obama’s “lead” has eroded? I don’t think so.

Look, I’m not saying everything is unfolding in this election precisely as anticipated – every campaign has unexpected twists and bumps in the road. But if you told me back at the start of September that this election would be essentially tied with less than three weeks to go, I would have thought you were reading my posts!

Which lead us to tonight’s debate. I’ll spare you a rehashing of the ubiquitous “Five Things Candidate X Must Do To Win” comments, and instead simply remind you to listen to what the candidates say more than watching how they say it. Candidates’ posturing and body language is a vastly over rated phenomenon, in my view. While I expect Obama to come out more energized, and to be more pointed in his critique of Romney’s policy platform, I don’t think there’s a lot of room left to change the campaign narrative on either side. This election is about where it should be, and if history is any guide, we aren’t going to see Obama move more than 2 polling points – at most – in either direction.

I will, of course, be live blogging the event. We’ve upgraded our blogging program to make it easier to comment (so I am told!), so I hope you’ll join in. Remember, this is the most crucial event in the campaign so far – I know this because most of the talking heads told me so. And they can’t be wrong.

I’ll be back on at about 8:45. See you then…. .