Later this year, Japan plans to dump contaminated water from the Fukushima nuclear plant into the Pacific Ocean, and then continue to do so for the next 40 years.

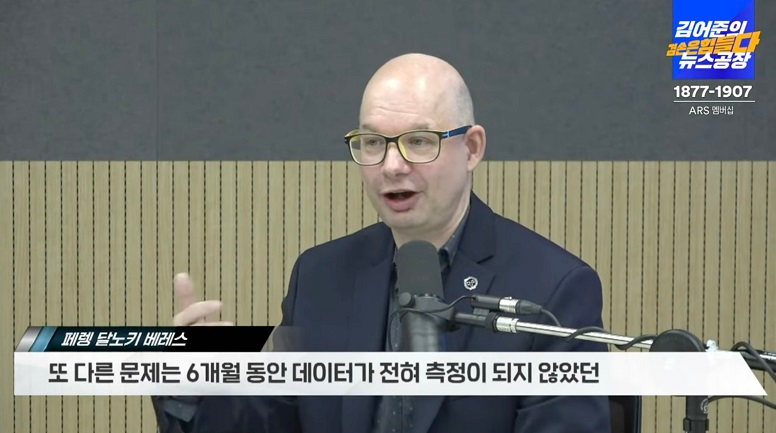

Unsurprisingly, this plan has troubled many, including scientist-in-residence Ferenc Dalnoki-Veress.

Over the past two years, the physicist has been working on team of scientists tapped to advise the leaders of 18 Pacific Island nations as they engage with Japan and TEPCO, the second most powerful nuclear company in the world.

In a way, Dalnoki-Veress’s involvement with this all started with a PowerPoint deck.

Japan was sending regular updates on the project to the Pacific Island Forum (PIF), an intergovernmental organization coordinating regional security and environmental issues. However, the PowerPoint presentations were inscrutable to all but experts in the field.

“A colleague has commented that science can be used to help, clarify, or obfuscate,” said Dalnoki-Veress, who has long chosen to work at the intersection of science, policy, and politics.

In this case, it clarified that the PIF needed help understanding the science in a way that could inform their entreaties to Japan. They had the wisdom to form a global panel of experts to advise them, including Dalnoki-Veress of the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. The five scientists all bring different expertise—nuclear engineering, the effect of radionuclides on marine organisms, ocean currents, nuclear regulations, ecotoxicology, and more.

“I feel humbled to be part of this team,” said Dalnoki-Veress, who led data analysis.

The project initially seemed straightforward. The PIF put in a request to know exactly what was inside the 1,000 tanks of water. Two months later, they received 19 messy spreadsheets.

“It’s like a student handing in a poorly written assignment with no effort,” said Dalnoki-Veress. “It was so upsetting. I found so many problems. Then when we met with TEPCO, they dumped a massive PowerPoint two hours before the meeting. I have a day job!”

The data raised concerns—especially the lack of data on which to base this major transboundary and transgenerational issue. In August 2022, the scientists took their private concerns much more public in an op-ed for the Japan Times. In January 2023, they spoke out in Science magazine, calling for more data and deliberation. The International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War and the National Association of Marine Laboratories have both come out against the plan. This spring, Dalnoki-Feress presented to the National Assembly of Korea.

“But we haven’t stopped it,” he said.

As of the publication of this article, Japan still plans to release the water.

What exactly do you do with 1,000 tanks of contaminated water?

When the Fukushima nuclear power plant was hit by an earthquake in 2011, three reactors melted down. The molten fuel debris continues generating heat. Workers prevent overheating by pumping 150 tons of water a day, which is stored in tanks on site.

“The accident did not end, in the sense that vast quantities of water are being generated,” said Dalnoki-Veress.

Now TEPCO has 1.3 million tons of contaminated water in 1,000 tanks with more water and claims to be running out of space.

The water volume is 110 cubic meters (110 meters is about the length of an American football field).

So what are the options?

The cheapest one is to dilute and dump the water. That is not unprecedented. Over 400 reactors worldwide release tritiated water into the sea, including in China, Korea, and the U.S.—the countries who have been most vocal against Japan dumping the water.

“But this is not normal operations, and you can’t use the normal playbook,” said Dalnoki-Veress.

The volume of water is massive, and the timeline for release is long. Also, only one-quarter of the tanks have been tested. The dilution plan is focused on tritium, but there are many other compounds in the water. Most concerning is that the tritium doesn’t stay in the water—it gets concentrated as it moves up the food chain.

The scientists have proposed several alternatives. One is bioremediation: pumping wastewater through tanks full of oyster species that consume plankton and incorporate radionuclides into their shells, reducing the time needed for storage. Another is to make concrete for roads or bridges using the treated water. This has many benefits: accelerating water processing and removal from tanks, not impacting the fishing industry, and being entirely non-transboundary. This process helps to protect the environment by safely containing tritium inside the concrete, preventing external radiation exposure and saves a significant amount of fresh water, contributing to environmental conservation efforts.

Another option is to simply wait. Tritium has a 12.3-year half-life for radioactive decay, so in 40 to 60 years, more than 90 percent of it will be gone.

As soon as you bring living creatures into something, everything becomes much more complex.

— Ferenc Dalnoki-Veress, Scientist-in-Residence

A very public scientist

If you’ve tuned into the media in Japan or Korea lately, you might catch Dalnoki-Veress breaking down the issue and sharing the panel’s concerns. He’s been featured and quoted in over 20 media stories since January.

The past year has been unusual, but then again, little has been typical for Dalnoki-Veress, whom Physics journal called a “physicist dressed as a policy wonk.”

A Dutch citizen, he started his career as an experimental physicist, working in labs in Germany and Italy.

Then came the Bush White House’s claims of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) in Iraq and the war.

“I was frustrated with how science was not communicated well,” said Dalnoki-Veress. “There’s a reason why physics is important besides a tenure track position.”

The world was reminded of this when the Fukushima power plant melted down in 2011.

“Every meeting during that time was about Fukushima, asking ourselves: what can we do to prevent this from ever happening again?”

He joined as scientist-in-residence at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies in 2010, where he focuses on ensuring elected officials have the information they need to make informed decisions and teaches courses on science and technology for policy students.

“I love my job because I learn something new every day,” he said.

Questions lead to more questions

Whatever Japan ultimately decides to do, Dalnoki-Veress has been left with much bigger questions.

In his training as a physicist, the problems were approached mathematically. If you know certain factors, you can calculate others, whether that is the increased incidence of cancer from radiation or how much dilution will be needed to meet a safe threshold.

“If you think about the ocean as a bucket of water and you add a bit of contaminated water, it will be diluted like cream in coffee. That’s kind of how I came into it, thinking about the problem,” he said. “However, as I’ve learned from my colleagues on the biology side, as soon as you bring living creatures into something, everything becomes much more complex.”

The phytoplankton absorb the tritium, the zooplankton eat the phytoplankton, then baby tuna eat the plankton, on up the food chain, which becomes a very different long-term problem for fisheries and people across the region.

“It’s much more complicated and nuanced than I ever thought,” said Dalnoki-Veress.

Follow that line of thought, and you will start to question the standards themselves. The International Atomic Energy Agency currently supports Japan’s plans to dump the water, as it complies with current regulations.

“There is a need to revisit the standards on the effects of radiation. Because hundreds of reactors are already dumping this stuff,” said Dalnoki-Veress, who notes that time is not on their side.

The team of scientists have offered to design the experiments Japan and TEPCO need to understand the biological uptake, trophic transfer, and bioaccumulation on key radionuclides in marine organisms and sediments. So far, that offer has been declined.

“In the end, we will continue to advise the PIF secretariat as best of our ability and as honestly as we can based on the science we know,” said Dalnoki-Veress. “We deeply hope that Japan will change course and change their mind to release this contaminated water into the sea.”