I recently took the class “The Printed Book in the West to 1800″ at Rare Book School at the University of Virginia. Several colleagues had attended classes there and told me they were excellent, and it did indeed turn out to be a fantastic experience. Classes were held Mon.-Fri., 8:30 to five, four sessions each day, with one session each day being hands-on in UVA’s Special Collections. There were only twelve people in the class. My teacher was Martin Antonetti, the Special Collections Librarian at Smith College. Martin is an excellent lecturer and has an amazing depth of knowledge of the history of the book, and world history in general.

I recently took the class “The Printed Book in the West to 1800″ at Rare Book School at the University of Virginia. Several colleagues had attended classes there and told me they were excellent, and it did indeed turn out to be a fantastic experience. Classes were held Mon.-Fri., 8:30 to five, four sessions each day, with one session each day being hands-on in UVA’s Special Collections. There were only twelve people in the class. My teacher was Martin Antonetti, the Special Collections Librarian at Smith College. Martin is an excellent lecturer and has an amazing depth of knowledge of the history of the book, and world history in general.

Despite the title of the class, we actually began our week with a survey of the book in the manuscript era. Just as the printed era is now overlapping with the digital era, the manuscript era overlapped with the era of the printed book for about two hundred years. Early printed books were often trying to imitate manuscript books. We explored the context of manuscript production, the role of the church and the rise of humanism, and the role of literacy or lack thereof. We learned a lot about the invention of paper, paper manufacturing, and developments in metallurgy that made the invention of the printing press possible.

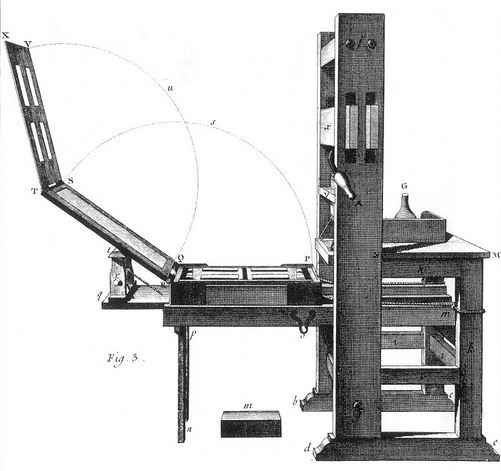

Of course we learned a lot about Johannes Gutenberg and his invention of the printing press in 1450. We studied various forms of early fonts, explored their origin and politics, and learned how they can sometimes be used to identify the date and location of the publication of a book. We learned about the way an early print shop operated, and explored the influence of the church and the impact of the guild system on the restriction or advancement of printing and publishing. Each of us got to operate a reproduction of a 16th century hand press and print a leaf that we then folded into a signature. (The press looked exactly like the one pictured above.)

We studied early bindings, styles of sewing, and learned about the many kinds of animal hide, cloth, and paper that were used to cover cases. A book conservator from NEDCC demonstrated book binding. We also examined many different styles of bindings and binding decoration. We learned about the relationship between text and pictures, the history of illustrations, and the various methods of producing images for books. Antonetti also covered the history of libraries and book collecting.

Throughout the week we examined materials from UVA’s Special Collections library seeing everything from a stunningly beautiful 14th c. illuminated choir book to18th century printed books bound in amazing Grolier style bindings. I also attended an evening lecture “Bibliography in the Digital Age”, by Stephen Karian, (some of our catalogers would have enjoyed this a lot, I only somewhat did) and a second forum “Thinking Inside the Box: Protective Enclosures for Your Collections” by Kara McClurken, Head of Preservation Services at UVA. (I tried to connect with Kara for a tour of their work units, but schedules didn’t allow it… hopefully another time.)

So why does it make sense for me to study early printed books now, at the dawn of the digital age? The short answer is, I’m now going to be much more involved in the preservation of our Special Collections and we have many rare and valuable items to care for. I can now tell the difference between hand laid and machine manufactured paper. I can tell if an illustration was printed from a wood block or from a plate, and whether that plate was etched or engraved. I can evaluate whether a book’s case is the same age as the text block or newer. I understand how paper and books were produced… etc. Because I have a much deeper understanding of how books were made during the first part of the print era, I am better equipped to make conservation treatment decisions about those materials.

The book is changing a great deal as we transition from the print to the digital era. With e-readers of one model or another becoming more and more ubiquitous, most of us are changing our attitude toward our printed collections. We’re now thinking of the vast majority our printed books as ephemeral, when just over a decade ago we thought of them as permanent. As attitudes concerning typical books evolve and they become less valued, I believe our Special Collections, those books whose physical characteristics make them unique, rare, beautiful, or particularly interesting, will become more and more valued. That’s why I’m glad I’ve learned more about those materials so I can more readily facilitate the preservation of them.

http://www.rarebookschool.org/courses/history/h30/