We humans have a habit of storing memories and feelings just about everywhere. The house, the car, the cat, articles of clothing, coffee mugs, lost teeth, and locks of hair. Really, anything will do as a repository for the moments in our lives that we would rather not forget. I have drawers and boxes full of things that I can’t bring myself to discard on account of the memories I’ve associated with them—trinkets I’ve bought while traveling, stuffed animals my girls no longer covet, threadbare shirts from meaningful periods in my life—all sorts of objects d’ordinaire that still, all these months or years hence, instantly reanimate sacred memories, the crosshatched shadows of my former self. Whatever’s within easy reach—physically, mentally, visually—is fair game to be transformed into a visceral flash drive to hold the thoughts and scenes of life that I hope will endure.

I find works of art often nominate themselves for this sort of duty, perhaps because I so often turn to art in moments when my soul is in need of reflection, or, perhaps just as likely, because art is so naturally adept at capturing the common denominators of human existence.

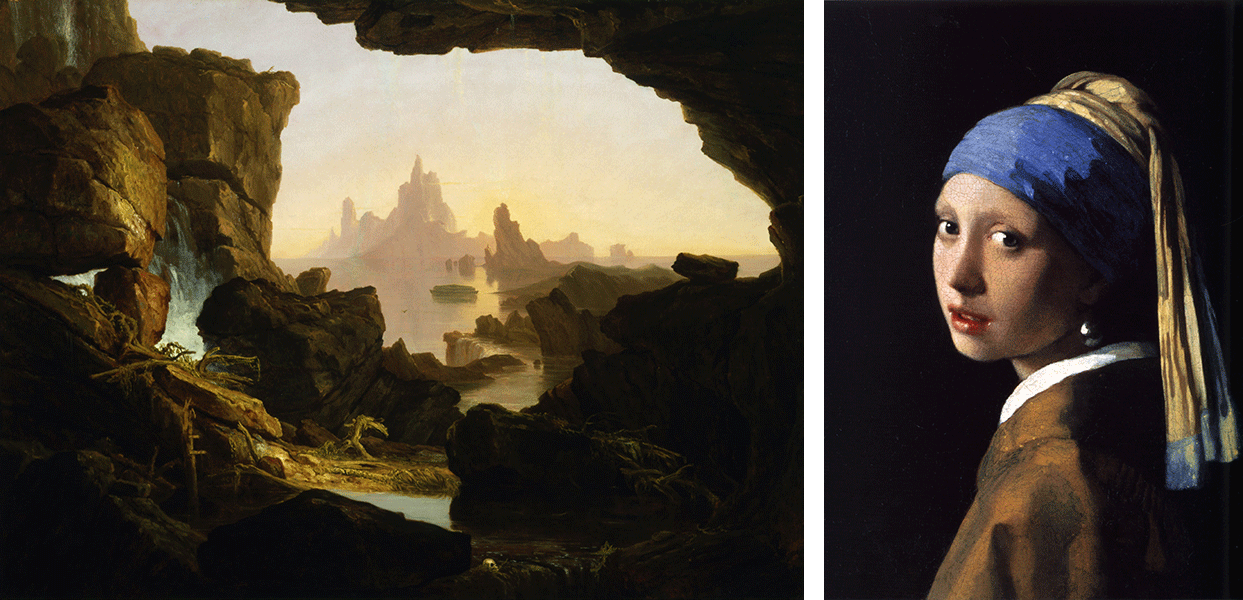

Thomas Cole’s 1829 painting The Subsiding of the Waters of the Deluge holds the ghosts of a fair few of my feelings related to the 9/11 attacks, in part because it was included in an exhibition we were mounting at the time, but more so for its apt depiction of, literally, a watershed moment. As must Noah have thought, so did I at the time, that the world would never be the same.

Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring immediately sets me to contemplating the durability of consciousness and the possibility of other lifetimes. On one level, her likeness reminds me of a pre-school classmate for whom I had a fondness, the earliest memory I have of the warmth of friendship and indeed one of the earliest memories I have from this life. On a more esoteric level, though, I have a vague but unshakeable sense that I know her from another time—from her time—so the very sight of her invariably leads me to wonder about the timelessness of my own soul.

My most recent fine art horcrux is Winslow Homer’s Eight Bells. The painting, in the collection of the Addison Gallery of American Art at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, is a moving monument to the average Joes of the late nineteenth century seafaring life. The etched version, arguably one of Homer’s best, graces our collection and, with its more dramatic cropping and forefronted figures, is to my mind a more intimate, more incisive rendering of the moment. And it’s been on my mind a lot these last few days.

1986.060.

This time last year I was spending with my father what would be the last two weeks of his life. Frail from illness, he was more or less confined to bed rest, so I spent many hours sitting with him in his room surrounded by the few treasures from his life he chose to keep close. One of those items was the ship’s clock from the schooner Cordelia E. Hays, captained by his grandfather at the turn of the century, and as my father’s sense of time was now beginning to fade it was my job to make sure that the clock was wound daily.

My father, like his grandfather, had a lifelong relationship with the ocean, and he keenly enjoyed recounting tales of his travels while serving in the navy as well as time spent aboard his own vessels. He was also an astute student of naval history, and he had a particular fascination with the Titanic that went beyond a mere thirst for learning. As do I with that pearl-earringed girl, so too he had a sense that his connection to the Titanic may have been more timeless than he in this lifetime could explain. And that ship’s clock, whose chime had brightened his house faithfully every half hour throughout his adult life, was his daily reminder of the ways in which the ocean had animated his sense of purpose.

The chiming of a ship’s clock is a mechanized version of a longstanding tradition stemming from the basic function of keeping time and marking the changing of the watch while at sea. One bell is struck at 12:30, two bells at 1:00, three bells at 1:30, and so on until eight bells at 4:00. Then the watch is changed and the cycle repeats starting with one bell at 4:30, etc. In Homer’s Eight Bells we see two fishermen at the eight bell watch using octants to find their latitude by measuring the peak height of the sun at local noon. (Here’s a video showing how it would have been done.) Homer’s sensitively rendered depiction of the scene forces us to recognize the task not as another mundane moment in the life, but rather as one of the rituals that impart a sense of hallowed order to the day.

In addition to marking the end of the watch, eight bells can sometimes be struck to mark a sailor’s death, a poetic euphemism for the end of his or her watch. This latter symbolism is what brought Homer’s etching to mind then as it does now. There, on the coast of Maine, not even a stone’s throw from Prout’s Neck where Homer spent the last years of his artistic career, I coaxed from my father the last details of stories he had long promised to tell, stories of a life well and simply lived. And all the while the chiming of that clock marked the waning hours of our time together.

Myriad details—stories he told, his characteristic mannerisms, the special Christmas dinner he and I shared, the events he considered to be the highlights of his life, the things he would have done differently, the feelings I had during those two weeks, the lessons I’ve learned from him, the legacy he leaves behind—are now, in my mind, forever tied to that work of art like near field communication, popping up whenever my mind wanders close. And vice versa. Whenever I think of my father, the uncommon commoner with a love of the sea and a knack for making the ordinary feel extraordinary, my mind freely wanders to Winslow Homer and I am washed in waves of warm reminiscence. Such a burden of reverence and recollection have I bestowed upon that etching. But, like all works of art, I know it’s up to the task. I know that each time I stop to reflect upon it all of those embedded memories will come flooding back never having been further from mind than the ebbing tide.

On the morning of his death I chose to wait in his room for the coroner to arrive. As I waited, the clock faithfully chimed eight bells. End of the watch. End of his last watch. Death of a sailor. Birth of a memory.

beautiful mate. Just damn beautiful.

Thanks!

A beautiful and thoughtful essay. And your choice of images is superb. Thanks.

Thank you!

This certainly is a poignant, touching and a memorable tribute. Thanks for sharing.

I’m glad it resonated with you. Thanks for reading.