“The artist who searches for subject matter is like someone who can’t get out of bed without understanding the meaning of life.” –Fairfield Porter

When I think about pencil drawings my mind inevitably wanders to Robert Frost’s Mending Wall. “Something there is that doesn’t love a pencil drawing,” I tell myself. It’s a perplexing association to be sure, but I think it must have something to do with the fact that drawings, pencil or otherwise, are often intended to be stepping stones along the path to a grander vision, so they tend to feel unfinished, imperfect. They are forever being mended—erased and redrawn atop patches of semi-intended smudging—until they reach a state in which they can conceivably hold an idea long enough to fatten it in some other medium for market. A drawing is usually version 1.0

But not always.

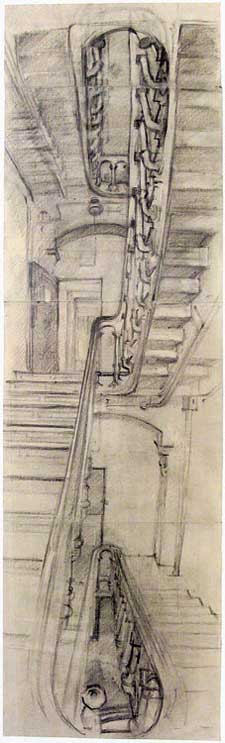

At the Museum’s annual Purchase Party in November of 2011 the Friends of the Art Museum voted to spend their available acquisition dollars to bring to Middlebury a drawing, Stairway in Building E, Snug Harbor, by Rackstraw Downes (currently on view in the museum’s entrance court, but it will come down soon, so don’t waste time getting here). The drawing, part of a suite of works Downes produced from the Snug Harbor site, is elegantly rendered, yet it still maintains an informality that would seem to indicate incompletion as a foregone conclusion, so one might easily assume that it’s a stepping stone. And perhaps it was intended to be, though despite some searching I have yet to find a more substantial work in which he included this stairway. So, is it just a preparatory study that was ultimately deemed unfit for deeper exploration? Or is it a final destination? And does it matter? Must we know which in order for it to have value?

The art market, I’ve noticed, prefers to know. Final destinations bring the big bucks while sketches from the journey fetch more modest sums. We’re smitten with the grand oeuvres, the defining moments in an artist’s career. We value the rare polish of culminations above the dusty, smudgy proliferation of the miles traveled betwixt.

But life is lived while traveling from A to B. The real moments, and the mundane spaces in which we pass them, lay along those miles betwixt, and the culminations are as perfect and valuable as they are because they are imbued with the memory of all the (im?)perfect moments along the way.

Downes’s Stairway, be it study or final destination, is a beguiling moment, a gap in the wall in need of mending. Its unnatural perspective forces me—taunts me, really— to figure out where the artist was standing as he sketched. (Was he on a ladder?) The field of view this drawing endeavors to record is so vertically expansive that Downes had to tape together four pieces of paper to create a canvas tall enough to accommodate it, and the interior landscape of this stairway is compressed just enough to signal unconsciously to the eye that something isn’t quite right. So I stare at it hoping that the illusion will right itself as though it were one of those three dimensional prints that magically reveals a secret scene if you scrunch up your eyes just right. There are moments when I think I’ve managed to reconcile it—I’m tempted to say, á la Frost, “Stay where you are until my back is turned!”—but they’re fleeting, and ultimately the illusion does not right itself. The image remains imperfect, unresolved. Stairway 1.0.

But its imperfection makes it human and draws me in to explore the space and to absorb its mood. It’s light and open, inviting even, and I feel nonplussed at the lack of other warm bodies coming and going. Surely, there must be other people around. If not now, certainly I can feel the presence of those who have climbed here before. I can see and smell the residue of years’ worth of skin oil on the bannister. I can hear the echo of footsteps. This drawing, with its challenging vantage point and towering viewing angle, is alive in ways that many seminal, career-defining canvases are not. It has meaning more than value.

As such, it needs regular tending, no longer by the artist, but rather now by me. Time spent in this stairway has begun to reveal gaps in the walls I construct to separate imperfection from completion, larger purpose from art for art’s sake. To spend time within the Stairway in Building E is to spend time mending my assumptions, reconstructing my perspective. Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder if I could put a notion in my head.

As an addendum to this, I offer you the fruits of a moment of felicity. Around the time that the Friends were voting to purchase this drawing our staff was also in the process of rearranging our office spaces, and in that endeavor we uncovered a cassette tape (flashbaaaaaaack!) with a recorded interview between our Chief Curator Emmie Donadio and Rackstraw. The interview, which I promptly digitized, hails from the summer of 1991 when we hosted an exhibition titled Fairfield Porter and Rackstraw Downes: The Act of Seeing. It’s a delightful conversation that few have had the chance to hear, and, with the artist’s enthusiastic permission, I make it available for you now, here (35 MB). If I could put a notion in your head, I would tell you to whip out your smartphone and listen to the interview while you contemplate this drawing. Hurry, there isn’t much time before it comes off the wall.