By: Amy Morsman, Professor of History

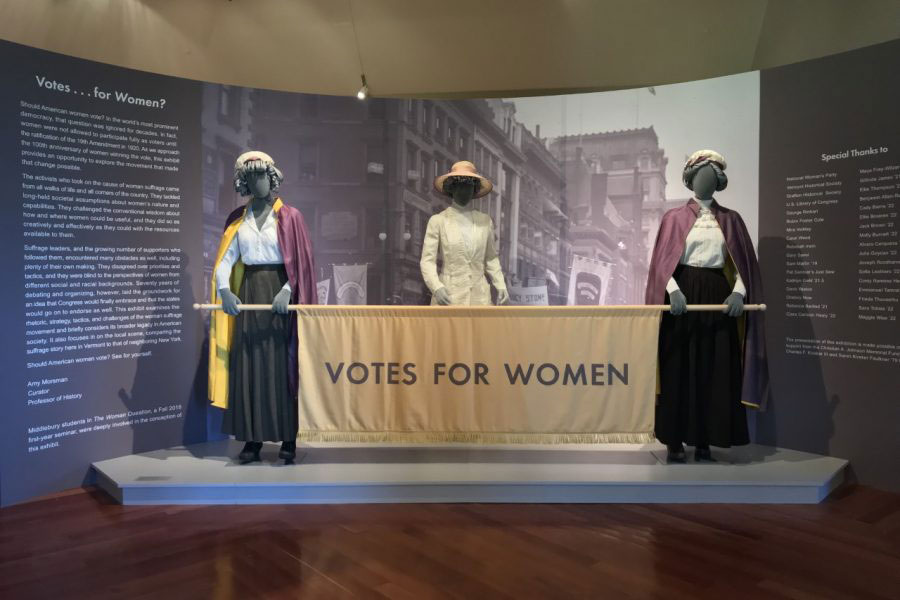

This time last year, the Museum opened a new exhibition entitled “Votes…for Women?” I served as curator of that exhibit, but I had considerable help, not only from an extraordinary team of talented museum professionals and faculty/staff colleagues, but also from a whole seminar full of students—15 first-year students—who had explored the topic of the American woman suffrage movement with me throughout the Fall semester of 2018.

Through class discussions and research projects, my students signaled to me the elements of the suffrage story they found most compelling. In considering what parts of this history were worthy of inclusion in the coming exhibit, they came back repeatedly to the complexity of the movement. They were impressed by the different arguments and tactics used to win the vote, but even more so by the range of people working to advance as well as resist the cause. Capturing that diversity and displaying it in visual form was a challenge we embraced but could not entirely overcome.

We confronted together the reality inherent to the discipline of history: that our work is shaped largely by the stuff left behind. When interpreting the past, historians must depend upon the materials that have survived the ravages of time. More often than not, our conclusions are influenced by those artifacts that are most accessible, those which decision-makers—mainly elites—in a given historical moment considered important enough to reveal, engage with publicly, and save. In our quest for exhibit pieces most able to demonstrate a fuller, more nuanced, visual suffrage story, my students and I made decisions as creatively as we could to work around that disciplinary limitation.

Our most telling case in point?—Suffragists of color. African American, Native American, Asian American, and Latina women were a part of the movement, sometimes in significant numbers; they were vocal and effective in pushing the issue of women’s right to vote within their own communities and well beyond. Because of the entrenched race-based discrimination they endured throughout this time period, these suffragists operated largely outside of the most prominent and mainstream suffrage organizations, which white women controlled for their own benefit. Most suffragists of color chose instead to labor for the cause within familiar channels: the church, club, and mutual aid associations where they had flourished as reformers for years. Nannie Helen Burroughs, for example, understood that gaining the right to vote would help advance a larger priority, the creation of ample educational opportunities for African American women. Already a leader for racial uplift within the Woman’s Convention of the National Baptist Convention, Burroughs held firm to her goal of establishing the National Training School for Women and Girls.[ref]This information on Burroughs’s reform work came from this record in the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Online Catalog: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/98503266/. For more detail about the activism of Nannie Burroughs, see Cheryl Gilkes, If it Wasn’t for the Women – Black Women’s Experience and Womanist Culture in Church and Community (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2001).[/ref] That noble endeavor to counter the deplorable effects of Jim Crow has been more readily documented than her work as a suffragist.

Even the Library of Congress, which holds the most expansive collection of photographs chronicling American life, had little to offer as we searched for images of suffrage activity by Burroughs and other women of color. We were able to tap from the Library of Congress’s resources the best visual examples of their reform efforts converging from a number of fronts. It was, however, a challenge, not only because these busy women folded suffrage activism into their ongoing work for civil rights, but also because the most powerful suffrage leaders and members of the mainstream press, all of them white, did not prioritize the contributions of women of color to the movement and sometimes went out of their way to ignore or shroud their presence from public view.

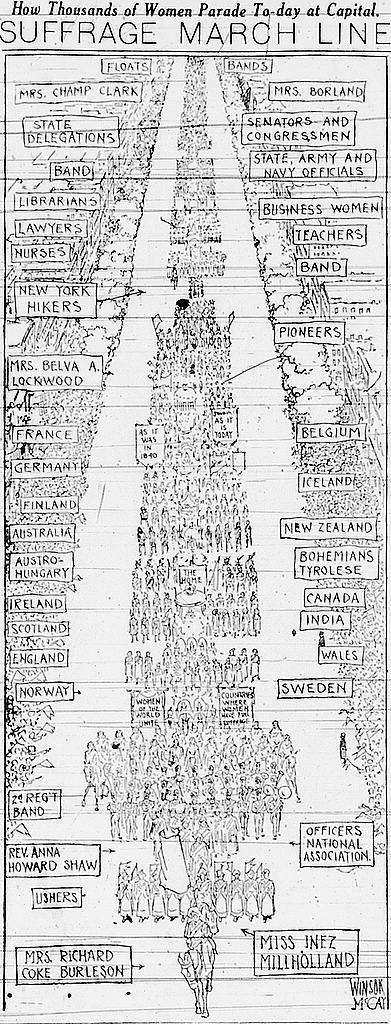

The 1913 suffrage parade in Washington D.C. provides a fitting example of this erasure. White suffragists looking to create greater visibility on the national stage, planned a woman suffrage parade to take place in the nation’s capital in March, on the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration as president. With all eyes on Washington at that time, they aimed to show supporters and skeptics that women’s call for full participation in this democracy was gaining ground. They were proud to demonstrate in this parade the depth and breadth of support for woman suffrage both globally and domestically, highlighting the involvement of women from a variety of occupational backgrounds, especially those such as teachers, businesswomen, and nurses, who brought with them the status of a higher education and work in the professions. Race, however, marked the line where the organizers’ image of inclusivity abruptly stopped. African American women, regardless of their class status, educational background, or years of reform experience, were asked to march at the back of the line, out of sight until the very end.

(Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Online Catalog)

Catalog)

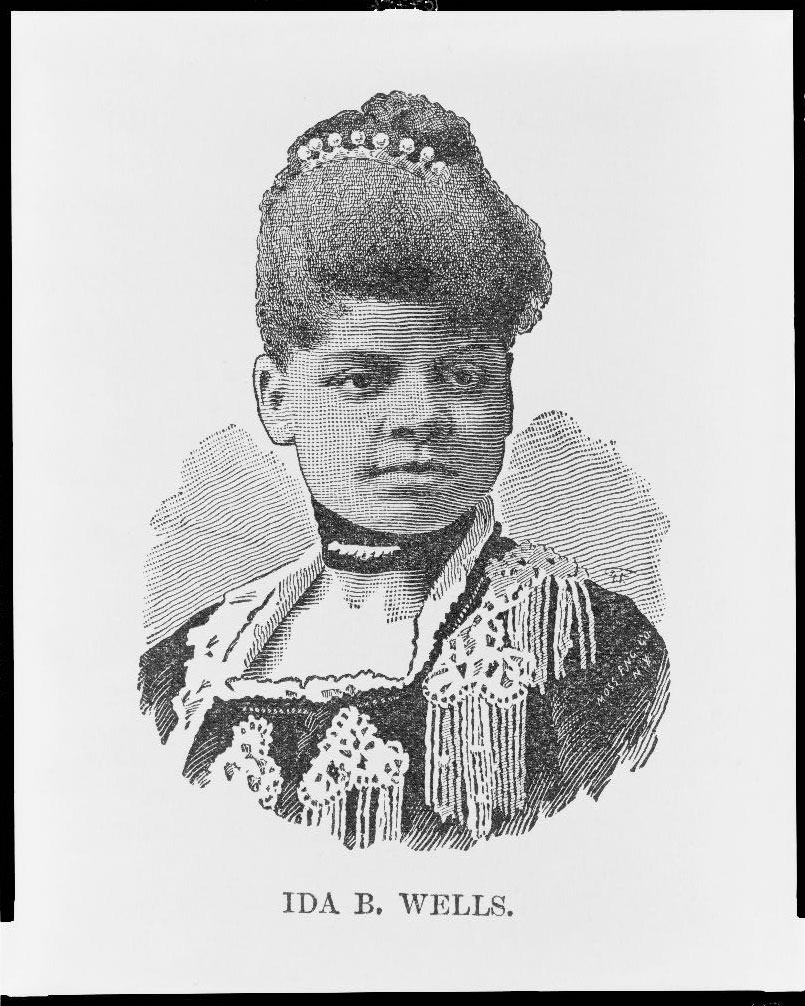

Ida Wells-Barnett, already a woman of national significance in Progressive Era reforms and known for her decades of brave work calling attention to the practice of lynching, traveled to Washington intent on marching with the rest of the Illinois suffrage delegation. Parade organizers told Wells-Barnett that she could not do so, because of the color of her skin and because of concerns for how detractors and the general public might respond to a racially integrated suffrage delegation. Stung by this decision, but not defeated, Wells-Barnett had her own way on that day in 1913. By waiting in the crowd and then quietly joining her white peers in the Illinois state delegation as they passed by, she refused to be hidden even though she risked her own safety in the process. Other women of color also challenged the requests of parade organizers for a segregated march, and some of them may have been successful in asserting their equal status as parade participants alongside white women.[ref]“1913 Woman Suffrage Procession,” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/woman-suffrage-procession1913.htm.[/ref] This suffrage parade was not the last time suffragists of color faced obstacles from the larger public and also from other women. For years, leaders of the most powerful national and regional suffrage organizations and many of their followers labored for a movement predicated on arguments of equality and inclusivity but chose not to see the irony of their own discriminatory actions.

The fight for women’s right to vote is an important episode in the making of American democracy. Sharing that story through a public exhibit at the Middlebury Museum was a rewarding and enlightening experience for me and my students. The discrimination baked into the nation’s past was on display there as well, shaping what we could get from surviving sources and what they chose to reveal or conceal about suffragists of color and their double struggle.