Note: The Middlebury College Museum of Art possesses a remarkable collection of Russian artifacts and family keepsakes made by the firm of the famous jeweler, Carl Fabergé. This essay by Adrian Kerester ’15, adapted from her April 2013 lecture and reproduced here with permission, explores Russia’s social history at the turn of the last century through an examination of and conversation surrounding Russian decorative arts and the culture of Russia’s ruling aristocracy.

Brief History of Fabergé

For many, the term “Fabergé” is equated with the luxuriously jeweled eggs crafted by the House of Fabergé for the Russian Imperial family during the last decades of Russian Imperial Rule. While these fabulously ornate and delicately crafted Easter eggs elevated the House of Fabergé to great popularity and international recognition during the 20th century, this famous Russian jewelry firm created luxury objects that extended beyond the realm of gifts meant only for special occasions. In fact, in keeping with the growing wealth of the middle class at the turn of the 20th century, Fabergé, along with other Russian jewelry firms of the time, produced a number of luxuriously decorated utility objects such as “picture frames, ashtrays and desk sets meant for the home and study.”[1] The Middlebury College Museum of Art proudly possesses nearly 100 of these ornately crafted items. The objects currently on display in the Cerf Gallery represent a small portion of this collection. While some of the objects within the collection are made by other famous jewelry firms, such as the Firm of Olovianishnikov, the Firm of Marria Semenova, the Firm of Ovchinnikov and the Firm of Klebnikov, for the purpose of this research project and presentation, I focused primarily on the objects made by the Firm of Fabergé.

About our donor, Nancy Leeds Wynkoop

This incredible collection of objects came to Middlebury College from a direct descendent of Tsar Nicholas I, who ruled Russia from 1825–1855. Our donor, Nancy Leeds Wynkoop (pictured at right with her husband Edward Wynkoop), was the great great granddaughter of Nicholas I, and we can trace her lineage back to the Romanov dynasty on both sides of her mother’s family. Before we dive straight into looking at a simplified version of an extremely complicated family tree, I want to shed some light on our donor. Nancy Leeds Wynkoop was born in 1925 on Long Island to Princess Xenia Georgievna of Russia and William Bates Leeds. Nancy attended Sarah Lawrence College and lived in various places throughout the East Coast before finally settling with her husband, Edward Wynkoop, in Woodstock, Vermont. Through her husband’s family lineage, Nancy was also a proud member of the Daughters of the American Revolution.[2] Suffice it to say, our donor has a pretty interesting family background! Through her own interest in art and through a distant familial connection (via her father) to Middlebury College, Nancy developed a relationship with the Middlebury College Museum of Art, donating her entire Romanov-Wynkoop collection of Russian decorative objects to the Museum when she died in 2006 from Parkinson’s disease at 81 years of age. Many, including myself, have asked, why Middlebury? Aside from Nancy’s connection to and thus awareness of Middlebury through her father’s cousin, who worked in the College Development office at the school, Nancy was drawn to Middlebury’s “substantial programs in the Russian language and Russian and East European Studies.”[3] As an institution located in Nancy’s beloved Vermont that had a relatively sizeable museum with the space and means to care for the numerous delicate and expensive objects, Middlebury college seemed to a be “a perfect repository for the collection.”[4] The endowment was made on the condition that the entire collection would be preserved and stored as one unit.

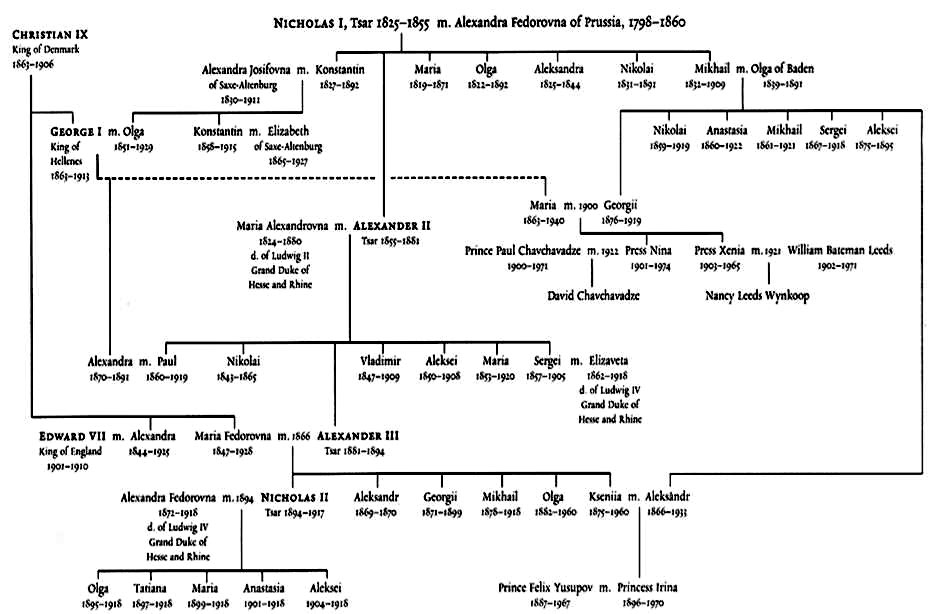

Family Tree

In order for us to truly understand the survival of these objects in light of the violent and chaotic events of both World War I and the Russian Revolution, it is crucial that we look closely at a very complicated family tree (see below)[5] that reveals the interconnectedness of much of Europe’s royal families. As I mentioned, Nancy was the daughter of Princess Xenia Georgievna and William Leeds Bates. Nancy’s mother, Princess Xenia, was the daughter of the Grand Duke Georgii Mikhailovich (who was the grandson of Nicholas I and the cousin of Tsar Nicholas II). Her mother (Nancy’s grandmother), Princess Marie of Greece and Denmark, also known as the Grand Duchess Maria Georgievna, was the great niece of Tsar Alexander III (the father of Nicholas II). This is to say that both of Nancy’s maternal grandparents were cousins with Nicholas II.

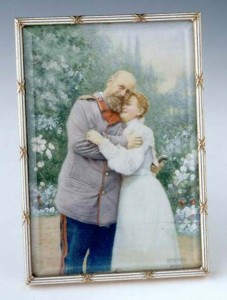

At left is a painted watercolor miniature of Maria Georgievna and her uncle Alexander III displayed in a Fabergé frame made of pure gold with enamel covering. The miniature is painted on ivory.[6]

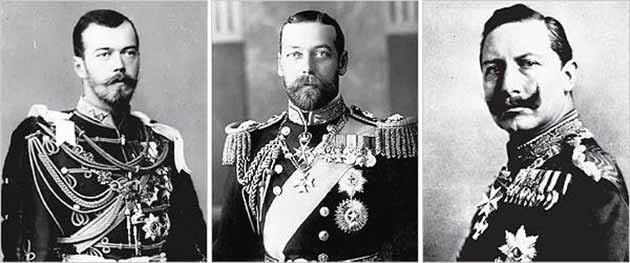

Now, this is where things get complicated! Returning to our family tree (above), we see that Tsar Nicholas II (from his mother’s side of the family) was a cousin of King George V of England (who ruled from 1910 until 1936), and that Nicholas II’s mother, Maria Fedorovna, was a sister of King George V’s mother, Alexandra. Both Maria and Alexandra were the daughters of Christian IX, who was the King of Denmark from 1863–1906. To make matters even more complicated, especially when considered in the context of World War I, both Tsar Nicholas II and King George V were distant cousins of Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany.

In the summer of 1914, Maria Georgievna and her daughters (Xenia and Nina) traveled to England to visit King George V and his family. During their visit, World War I broke out after the Austrian-Hungarian Empire invaded Serbia in the wake of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand the II. Maria and her two daughters never returned to Russia and the few keepsakes that they had packed with them for their summer vacation in 1914, such as religious icons and a few small framed family photos, are most likely included in the Museum’s collection today.

The survival of the majority of objects in the collection however, is primarily owed to Olga, the Queen of Greece (or Princess Xenia’s grandmother), who packed many of the family’s keepsakes from their home in the Caucuses when King George V of England ordered the Admiralty to rescue her and Empress Maria Fedorovna (Tsar Nicholas II’s mother) by warship in 1919 during the Russian Revolution.[7] Unfortunately, the Grand Duke Georgii Mikhailovich, Nancy’s grandfather, who had stayed behind in Russia during the summer of 1914, was assassinated along with his two brothers by the Bolsheviks in 1919.

About the Collection

The objects that survived both World War I and the Russian Revolution were created in St. Petersburg and Moscow during Tsar Nicholas II’s rule in the early 20th century. That said, these objects come primarily from the collection of keepsakes from the Grand Duke Georgii Mikhailovich and Grand Duchess Maria Georgievna’s home in the caucuses, where Princess Xenia grew up.[8]

This collection of prized objects exposes the love for the arts that the Romanov family possessed. In fact, Nancy’s grandfather, Georgii Mikhailovich, was appointed the director of the Imperial Alexander III Museum of Art in 1895 (which is now the State Russian Museum) and became the Patron of the Russian Art and Industry Society in St. Petersburg in 1904.[9]

What is most interesting about the arts produced during the reign of Nicholas II is that the objects reflect, in the intricacy of their design and fusion of styles, the tension between two conflicting worlds in Russia at the turn of the 20th century: that of the old, Muscovite Eastern Russia, symbolized by the city of Moscow, and that of the new modernized, Western Russia, symbolized by the city of St. Petersburg, otherwise known as Peter the Great’s “Window to the West.”[10] This collection of objects, commissioned by the Imperial Family during the first two decades of the 20th century, thus carries heavy social and political implications, the origins of which can be traced back to the rule of Tsar Alexander III.

Russian Decorative Arts under Tsar Alexander III

Under the reign of Tsar Alexander III (1881–1894), there was a huge upsurge in Russian Nationalism, consistent with the rise in nationalism across the continent of Europe during the second half of the 19th century. Alexander III, who is remembered today as the Nationalist Tsar, “adopted programs based on concepts of traditional Russian orthodoxy, autocracy and a belief in the Russian people, including the Russification of national minorities in the Russian empire and the persecution of the non-Orthodox religious groups.”[11] An oppressive and intolerant ruler, Alexander III increased censorship during his rule and cracked down on all forms of dissent. As an “opponent of the representative government,” which was the existing government of the time, Alexander III sought to reverse many of the liberal measures made by his father, Tsar Alexander II (the Tsar who was responsible for emancipating the Russian serfs in 1861).[12] Alexander III’s political ideal was a nation containing only ONE nationality, ONE language, ONE religion and ONE form of administration. As a result, Alexander III “impos[ed] Russian language and Russian schools on his German, Polish and Finish subjects and fostered the Russian Orthodox religion throughout his Empire.”[13] He “sought to strengthen and centralize the imperial administration,” taking privileges and governmental “say” away from the Gentry.[14] This solidification of Tsarist Imperial power and the imposed limitations on the people of the Russian Empire began to pave the path of dissent that ultimately broke out in the Russian Revolution.

Of most importance regarding our discussion of the social and political implications of the Russian Decorative arts at the turn of the 20th century, is Alexander III’s chief role in reinstating the fashion of wearing highly stylized Russian costumes at the court.[15] In his efforts to elevate Russian nationality, Alexander III had the impetus to develop all kinds of art objects and utility objects stylized in the old Muscovite tradition as a celebration of Russian Identity. It was Alexander III who commissioned the first Fabergé egg in 1883, thus starting the intimate relationship between the Imperial Family and the House of Fabergé.

Russian Decorative Arts Under Tsar Nicholas II

Influenced by the nationalist rule of his father, Tsar Nicholas II, who ruled as Tsar from 1894 until his forced abdication in March of 1917, shared a similar romanticized view of pre-westernized Russia, i.e. Russia before Peter the Great, the Romanov Tsar who founded St. Petersburg in 1703 in an effort to open Russia up to trade and political relations with Western Europe.[16] Inspired by Tsar Aleksei’s dominant and successful rule as the second Emperor of the Romonov dynasty, Nicholas II sought to reinforce his own position of power by referencing the dominance and strength of old (pre-westernized) Russia as a great world power through his utilization of traditional Russian ornament and decorative style.[17]

In fact, Nicholas II admired Tsar Aleksei so much so that he named his only son and heir to the throne Alexi after his revered ancestor. For Nicholas II, Tsar Aleksei’s reign symbolized both great power and peace as Aleksei expanded the Tsardom of Russia to include nearly 2 billion acres of land, and his reign was “characterized by a peaceful and harmonious period between the Tsar and the Russian people.”[18] In short, Nicholas II idealized the rule of Tsar Aleksei, and he used traditional Russian style to associate his reign symbolically with that of his honored ancestor. Nicholas II’s revival of Russia’s native visual culture and his references to the early Romanov dynastic rule—before Peter the Great’s westernization of Russia—is most salient in Imperial ceremonies, particularly the Coronation of Tsar Nicholas II in 1886.

The Coronation of Tsar Nicholas II

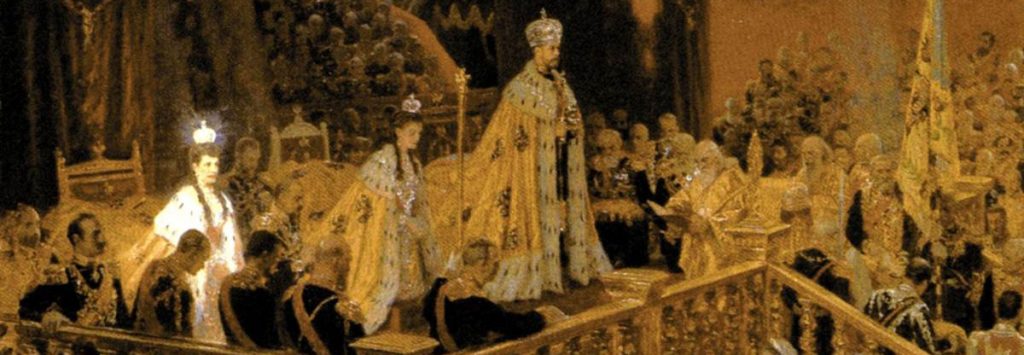

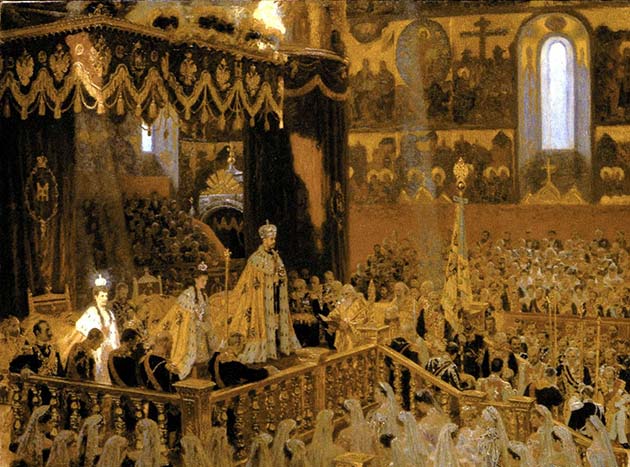

The Coronation of Tsar Nicholas II (pictured below) took place in May of 1886, and as was tradition, the ceremony took place not in St. Petersburg at the Winter Palace, which was home to the Imperial Family, but rather at the Kremlin in the city of Moscow, Russia’s formal capital and still pre-eminent city of the Russian Empire where the Tsar traditionally ruled and lived before Peter the Great.[19]

In preparation for the extravagant festivities, a considerable amount of money was allotted to repairing and decorating palaces, imperial theatres, and places for outdoor parties and spectacles in Moscow, all in Russian stylistic tradition, which was constant with his father’s Russian Nationalism and celebration of traditional Muscovite identity. The most prominent artists and decorators were engaged in embellishing the palaces and streets of Moscow, and special coins and medals were made to commemorate the coronation.[20]

Hordes of people from all over Russia flocked to Moscow to celebrate the coronation of the new Tsar. A coronation cup, like the one in our collection (at right and below) was made as a cheap freebie souvenir to commemorate his special occasion. The cup, which is made of enamel coated metal, is gilded with the Imperial Coat of Arms and was to be passed out at the Khodynka Field in Moscow following Nicholas II’s coronation.[21] The cup was meant to hold beer as the recipients were also to receive beer, compliments of the Tsar, in celebration of his new rule.[22]

Looking closely at the Imperial Coat of Arms, we see a double-headed eagle, with each eagle head imperially crowned. The eagle holds a scepter, or an ornamental rod symbolic of the power of the ruling monarch, and a globus cruciger, an orb topped with a cross, a Christian symbol of authority that refers to Christ’s dominion over the world. These two symbols emphasize the power of the Tsar, who was both the autocratic ruler of Russia and the head of the Russian Orthodox Church. Superimposed onto the body of the eagle is a shield donning the arms of Moscow, which depicts an image of St. George upon horseback after he slayed the dragon, a traditional iconographic image of Eastern Orthodoxy.[23]

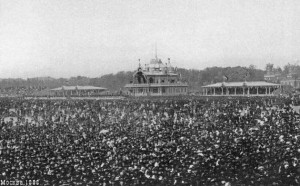

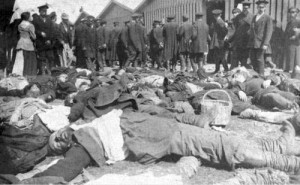

In the days following the coronation, a banquet was to be held for the people at the Khodynka field. On the eve of the banquet, rumors spread of the coronation freebies from the Tsar and people began to arrive early at the field in anticipation. By the early morning, thousands of people had already gathered at the Khodynka field (see images below). As word spread that there were not enough gifts for everyone, the crowd became hostile and a catastrophic stampede broke out, leaving more than 1,300 people dead and another 1,300 people injured. This event is what led to Nicholas II’s nickname as “The Bloody,” a name that seemed to be further deserved because of the anti-Semitic programs he implemented during his rule and his violent suppression of the 1905 Revolution, which is remembered today as Bloody Sunday.[24]

What did Russian Society Look Like during the Reign of Nicholas II

As Anne Odom wrote, “by the time Nicholas II came to the throne in 1884, Russia had modernized dramatically. Alexander II’s ‘great reforms’ and the end of serfdom in 1861 left the nobility, especially those of the lesser ranks, impoverished. Many nobles became civil servants, but the more talented ones went into business. The country was undergoing industrialization at an intense pace, and these new merchants and industrialists were rapidly replacing the established nobility and imperial court as tastemakers and community leaders.”[25] Despite the growing economic disparity between the wealthy and the poor, the expanding wealth of the rapidly growing bourgeois culture laid the foundation for the rise of market demand for luxury objects and decorative arts. The accumulation of small, expensive objects, such as those made by the Firm of Fabergé, reflected the Victorian manner of cluttered rooms with an abundance of seemingly “unnecessary objects” or knick-knacks.[26]

Dating back to the opulent display of power and wealth of Louis XIV in the 17th century, the expansion of luxury industries marked a “fundamental aspect of the modernization of all European monarchies.”[27] Luxury objects and decorative arts were seen as instruments of self-assertion of economic strength and power.[28] A “ruler’s display of native products demonstrated the technical and artistic sophistication of a prince’s realm.”[29] In addition to serving as a display of Nationalism, increasing production of goods domestically reduced the need to import costly goods from abroad and thus reduced a country’s economic dependence on others.[30] While Nicholas II certainly commissioned plenty of expensive art that served as an opulent display of power, the last Russian Tsar is often judged to have been a poor leader. Known as being a quiet family man, Nicholas II didn’t seem interested in the power of being a Tsar and his indecisiveness weakened his regime. The large number of luxuriously ornate Fabergé picture frames reflects both his interest in the decorative arts and his value of family, which was placed over the care of his Empire. Looking at two specific frames we have in our collection, the ornate design and wealth of precious materials used is astonishing.

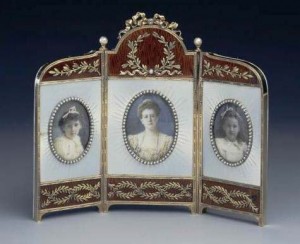

This triptych picture frame (left) holds miniatures of Maria Gerogievna and her two daughters, Princess Xenia and Princess Nina, all three of which are watercolor portraits painted on ivory. The frame itself is made of machine engraved metal that is painted with translucent light blue enamel so that the pattern of the engraving shows through.[31] Red and brown enamel on the top and bottom were used to simulate the texture and appearance of wood.[32] The frame is further decorated with pearls and diamonds and intricate details made from different shades of gold.

This picture frame (right), made of coppered silver, takes the form of the Roman numeral 10 and was commissioned to celebrate the tenth wedding anniversary of Grand Duke Georgii Mikhailovich and Grand Duchess Maria Georgievna, the grandparents of our donor, who married in 1900. The frame includes watercolor miniatures on ivory of Georgii and his two daughters, Princess Nina and Princess Xenia.[33] This frame was undoubtedly a possession of Maria’s, and it was most likely commissioned by the Grand Duke from the firm of Fabergé.[34]

In addition to picture frames, the Imperial family commissioned a number of small figures and glass animals, specialties of the Firm of Fabergé, which would decorate the cluttered interiors of their homes.

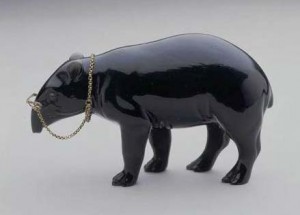

One such object in particular found in our collection is a small obsidian figure of a Tapir (left)—a shy nocturnal mammal inhabiting Central and South America as well as Southeast Asia—that was commissioned by Georgii Mikhailovich as a gift for the Grand Duchess Maria. According to the family story, Maria Georgievna was very nearsighted and wore a pince-nez, a popular style of spectacles in the 19th century, and one of her brothers supposedly said that she reminded him of a Tapir wearing glasses. This sense of humor was accompanied by jasper as well as lapis lazuli, nephrite, quartz, gold, and ruby, all of which were used to accentuate the innate beauty of the stone and decorate the glasses.[35] A very expensive family joke, to be sure.

Decorative Arts and Religion in Imperial Russia

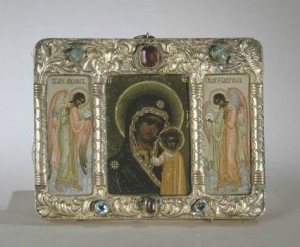

The Imperial family’s patronage of the arts went beyond commissioning precious gifts and luxurious utility objects and extended into the patronage of religious art as well. As the political system of Russia at the time was a theocracy, where the Tsar was also the head of the Orthodox Church, religious ceremony and official ceremony were often synonymous. As a very pious leader himself, Tsar Nicholas II “ensured that every official event included some form of prayer with clergy in attendance.”[36] Furthermore, Nicholas and Alexandra’s commitment to God led them to support various church projects, and they donated what seemed to be a constant flow of money to help build and restore various Churches throughout the Empire. “In 1901, Nicholas II approved the establishment of the Imperial Committee for the Preservation and Protection of Russian Icon painting. The committee’s goal was to improve the sorry state into which traditional icon painting had fallen.”[37]

A number of turn-of-the century icons are among the objects in our collection (see images, below). While, in the interest of time, I am unable to go into the details of explaining the significance of these objects, suffice to say that the huge revival of Russian Orthodox religious icons during the early 20th century attests to this close relationship Tsar Nicholas II developed with Russian artists and jewelers in an effort to reassert Russian Identity through the arts.[38]

Conclusion

As is often the case, the study of art is crucial to our further understanding of the social and political workings of a time in history. As I have hopefully exhibited in this presentation, these luxurious and opulent artifacts serve more than just beautiful objects to look at and treasure. By offering us a window through which to look, we are able to learn much about the tensions and relationships that characterized Russia during the last 50 years of tsarist rule. It is through these familial possessions that we can begin to grasp just how complex the political and social situations of Russia at the turn of the 20th century actually were. We treasure these objects not just for their beauty, exposition of artistic skill, and intrinsic value of the materials from which they are made and decorated, but also for their relevance in adding to and furthering the narrative surrounding the rule of the last Russian Tsar, Tsar Nicholas II.

Thank You

I would like to thank Emmie Donadio for being such an incredible mentor this year and for always encouraging and supporting my ideas. I also want to thank Professor Alexis Peri of the History Department for sparking my interest in Russian History during her enthusiastic History of Modern Russia lectures this past fall. And finally, I want to thank the late Anne Odom, Middlebury Alumna and Curator at the Hillwood Museum—although, sadly, I never met her, she had an extraordinarily high level of influence on this presentation as I relied heavily on her research and writings when preparing this talk.

Sources

Lincoln, W. Bruce, Sunlight at Midnight: St. Petersburg and the Rise of Modern Russia. Basic Books, New York, NY. 2000.

Curry, David Park. Fabergé: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Press, Virginia. 1995.

Odom, Anne. What Became of Peter’s Dream? Court Culture in the Reign of Nicholas II. Middlebury, Vermont: Middlebury College Museum of Art in association with Hillwood Museum and Gardens, Washington, D.C. 2003.

Professor Tatiana Smorodinska.

Michael T. Florinksy, Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s. v. “Alexander III,” accessed April 22, 2013, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/14102/Alexander-II

[1] Anne Odom, What Became of Peter’s Dream?: Court Culture in the Reign of Nicholas II, Middlebury, Vermont: Middlebury College Museum of Art in association with Hillwood Museum and Gardens, Washington, D.C., 2003. 21.

[2] Artefacts The Middlebury College Museum of Art Collection of Russian Artifacts, Gallery Talk by Emmie Donadio, October 3, 2008.

[3] Richard Saunders, introduction to What Became of Peter’s Dream: Court Culture in the Reign of Nicholas II by Anne Odom, 9. Middlebury, Vermont: Middlebury College Museum of Art in association with Hillwood Museum and Gardens, Washington, D.C., 2003

[4] Ibid

[5] Reference “Romonov Relations” on page 15 of What Became of Peter’s Dream: Court Culture in the Reign of Nicholas II

[6] Catalogue fig. 55 in What Became of Peter’s Dream: Court Culture in the Reign of Nicholas II, 95.

[7] Saunders, introduction, 10

[8] Ibid

[9] Ibid, 9

[10] Odom, What Became of Peter’s Dream?: Court Culture in the Reign of Nicholas II, 21

[11] Michael T. Florinksy, Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s. v. “Alexander III,” accessed April 22, 2013, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/14102/Alexander-III

[12] Ibid

[13] Ibid

[14] Ibid

[15] Lecture by Professor Tatiana Smorodinska

[16] Odom, What Became of Peter’s Dream?: Court Culture in the Reign of Nicholas II, 20-21

[17] Ibid, 40 & 42

[18] Ibid, 21

[19] Ibid, 35

[20] Lecture by Professor Tatiana Smorodinska

[21] Catalogue fig. 13 in What Became of Peter’s Dream: Court Culture in the Reign of Nicholas II, 87.

[22] Lecture by Professor Tatiana Smorodinska

[23] Odom, What Became of Peter’s Dream?: Court Culture in the Reign of Nicholas II, 38

[24] Lecture by Professor Tatiana Smorodinska

[25] Odom, What Became of Peter’s Dream?: Court Culture in the Reign of Nicholas II, 30

[26] Ibid, 50-52

[27] Ibid, 21

[28] Ibid, 23

[29] Ibid, 23

[30] Ibid, 23

[31] Catalogue fig. 55 in What Became of Peter’s Dream: Court Culture in the Reign of Nicholas II, 95.

[32] Donadio, 3

[33] Catalogue fig. 54 in What Became of Peter’s Dream: Court Culture in the Reign of Nicholas II, 95.

[34] Donadio, 7

[35] Catalogue fig. 46 in What Became of Peter’s Dream: Court Culture in the Reign of Nicholas II, 94.

[36] Odom, What Became of Peter’s Dream: Court Culture in the Reign of Nicholas II, 64.

[37] Ibid, 66.

[38] Ibid, 70-71