It’s not often that I get to make direct connections between an exhibition in the galleries and the collection of public art that we have on permanent display around the campus. The opportunity is probably there more often than I’m aware, but during my tenure anyway, the times when the similarities have been palpable have been rare. This spring, with Environment and Object • Recent African Art on view in several of our galleries there’s a theme that’s begging to be explored both inside and out. And it’s totally rubbish.

The truism “one man’s trash is another man’s treasure” is perhaps nowhere else as true as it is within the realm of art. Picasso’s Bull Head made from a bicycle seat and handlebars and Duchamp’s Urinal are perhaps two of the more widely recognized examples. Found objects—items that one person has jettisoned for lack of value only to be claimed by another and assigned new value—come in and out of our lives every day, but we seldom stop and think, “this has meaning, this is art.”

Some of the artists represented in Environment and Object have done exactly that. They’ve collected the detritus of our modern consumer culture, cast aside as garbage, and recontextualized it, redistributed its impact along the continuum of social perception.

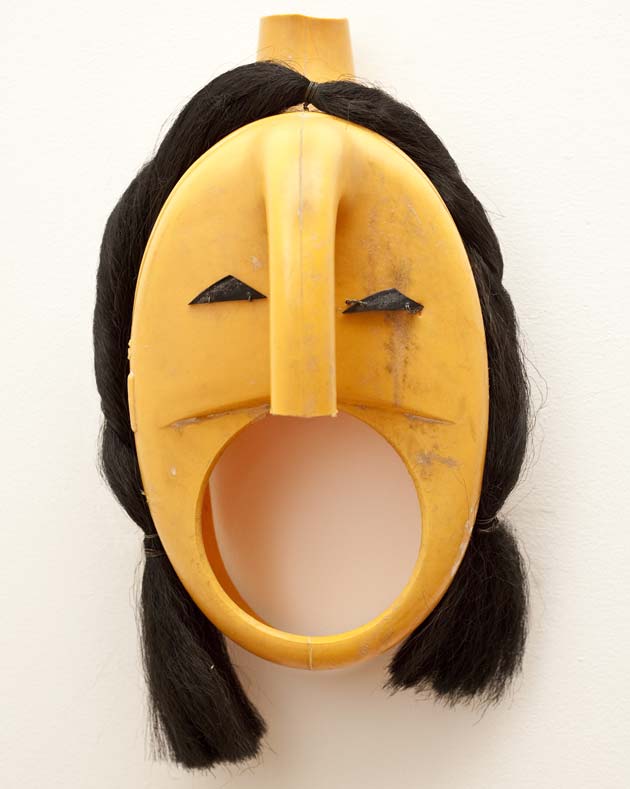

One of my favorite examples in the show is a mask, shown above, by Romuald Hazoumé. The genius of the piece is simple yet eloquent. He’s taken an ordinary plastic jug, an object that once held bleach or motor oil or some other equally quotidian substance, and with a few deft alterations and the addition of some hair he’s turned it into a female face full of character, depth, and intrigue. Confronting her in the gallery is an astonishing experience. I’m taken aback by the sense that I know her, that I’ve seen her somewhere before. Does she work here in town? Or wait, maybe I went to school with her. I bet she’s on Facebook.

Wow. From a plastic jug to Facebook in the blink of an eye. Behold the power of art.

But the real power of this piece of art, the deepest most nagging takeaway, is the realization that I could have done this myself. Plastic jug, hair, pair of scissors, and Bob’s your uncle. Really it seems as though it would be that simple. But I DIDN’T do it. There’s a regular parade of plastic jugs through the recycling bin outside my office—there are half a dozen there right now—but never once have I looked at one and thought “hey, that would make an interesting head.” The real power of this and other works of art assembled from found objects is their ability to re-mind, to reposition our frame of reference such that it can accommodate galaxies of new information that we had not previously known to exist within the grains of sand upon which we walk each day.

There are indeed a number of those “new galaxy” experiences awaiting visitors to the Environment and Object exhibit, and one of them has just been installed through a painstaking process that occupied two entire days. Senegalese artist Viyé Diba is in residence through Friday as he installs Nous sommes nombreux, et nos problemes avec…(We are many, and our problems too), a conceptual arrangement of stuff—lots of stuff, everything from photographs to vials and baggies filled with more stuff—designed to evoke downtown Dakkar within the confines of our Overbrook Gallery. The entire floor of the gallery is covered with Dakkar, and visitors will have to walk through all of the Dakkar to view the installation. I kid you not, there will be no way to avoid stepping on the Dakkar.

We’ve been talking about and planning for Diba’s visit for some time now, and all the while I’ve suspected that Nous sommes nombreux would soon inflame my imagination in ways heretofore unfulfilled. Well, he’s come through in spades, and I’d be shocked if others didn’t have a similar reaction to it. The end result can only be described as the aftermath of a Dakkar bomb explosion. But don’t take my word for it. Come to the museum and spend some time walking through downtown Dakkar. You’ll be challenged and fascinated, I promise.

But long after this show has been packed up and shipped off visitors to campus will still have the opportunity to be wowed by found objects every time they wander past the Franklin Environmental Center at Hillcrest. Along its curved wall sits Deborah Fisher’s Solid State Change, an aggregation of discarded tires and electrical insulation commissioned specifically for the site. It’s one of my favorite works in the public collection, and I’ve always been surprised that so many others claim to be repelled by it. They say it’s ugly, strange, offensive. Really?

I find Solid State Change to be such a stimulating piece. The contrast of colored electrical insulation with black tires is arresting and hypnotic, and there is a flow to the piece, a kinetic energy that reminds me of lava bubbling out of a volcanic fissure. Indeed, the piece is intended to evoke the metamorphic bedrock that sits below us, making the installation an almost interactive window onto the geology of our area. It’s like getting a taste of what would happen if seismic activity were to push the earth’s crust up into our backyard. The work has a primal presence about it, and the added contrast of the piece against the polished metal of the curved wall is stunning. What’s not to like?

In a way, Solid State Change is the ultimate in found object art. Not only is it constructed of discarded every day materials, but the piece is itself a found object in that the viewer really does just stumble upon it without warning. It’s a sudden revelation within the landscape, an “oh, say, that’s different” gift of a moment within your day. It, too, will reposition your frame of reference in a new galaxy sort of way. No longer are those tires scattered along the edge of the Garden State Parkway. No longer is that electrical insulation piled in a heap on the outskirts of some construction project. They are now bolted together in a molten reenactment of the upheaval that lives beneath and perhaps within us. They are now relevant to everyday life in a most surprising way much like Hazoumé’s mask or Diba’s explosion of Dakkar.

One other thing these works have in common: they are NOT in a landfill. They are on our campus and in our galleries ready to be appreciated.

If your inner geek is as strong as mine, then you may have guessed that the title of this post is a reference to a scene in Monty Python’s Holy Grail. As King Arthur and his faithful servant happen upon the anarcho-syndicalist commune centered around a castle on a hill, a peasant, entirely unaware of Arthur’s presence or his station in life, is busy collecting piles of mud. As she admires her work she calls to a nearby cohort, “Dennis, there’s some lovely filth down here.” In that moment, the rituals and pageantry so often thrust upon us by social convention are cast aside, and the very soil upon which we walk becomes exalted, commoditized even. Trash becomes treasure, filth becomes fabulous, and galaxies are revealed in a grain of sand. The same phenomenon is happening right here at Middlebury, in our museum and across our campus. Don’t tell me you haven’t noticed.

Steve, you’re right. You and I will likely never agree on most of this. You think of art as something with which we should choose to interact, and I prefer that it inhabits all sorts of spaces and that it hijacks my attention from time to time. You understand Solid State Change as an unsightly vehicle of deception, and I understand it as, among other things, a window onto the geology of our region. Since neither I nor any of my colleagues in the formal arts community are in any way desperate to justify the existence and placement of this work — we’re quite comfortable knowing that it has earned its place by virtue of the formal process through which its acquisition was approved — little remains to contend beyond aesthetics. We could trade comments back and forth to the end of time and never agree, so I see no purpose in continuing to focus on those issues.

I do, however, agree that a piece as challenging as Solid State Change requires obvious, readily available interpretation. We do have some of that in the form of digital content, but there is room for improvement in what we offer in that regard. Thoughtful suggestions, of course, are welcome if you have them.

In what way is it a window into the geology of the region? I mean, in reality, not in a “Picasso provides a window into human anatomy” kind of way. While the bedrock map of the region was the original starting point for laying down the strips of tires and insulation, the artist herself says that this match was quickly lost as their weight twisted the mass of discarded material into a new shape. I still think you are mythologizing the piece to make it seem to say more than it really does, parroting a public relations talking point without actually thinking about whether it is, in fact, true.

I’m afraid I can’t help you with your challenge of improving its readily available interpretation. To be honest, I think the interpretation that is currently provided on the stone tablets is quite accurate: “discarded tires and electrical insulation.” If you start adding in statements about it being a window into the geology of the region, you will be compounding the problem by adding factual inaccuracy to what is already an aesthetic disaster. If I were to write the signage, it would include most of the points I have already made in my comments, with the added thought that if this piece represents what happens by virtue of the formal process through which acquisitions take place, then something is clearly wrong with the formal process.

I started to leave a reply, and got a little long winded, so I turned it into a blog post. See http://sites.middlebury.edu/middland/2012/02/25/outdoor-art-in-context/.

Tim

Rock on, Tim. I’ve read your post, and really like the questions you raise and perspective you offer. I’ll try to respond more fully on your blog later, but the Cliff Notes version is that I appreciate your consideration of context in considering public (or outdoor) art, especially your thoughts that context include the full spectrum of landscaping, architecture, and emotional “feel.” Thanks for weighing in.

With respect, Solid State Change is, to many viewers, exceedingly ugly. Perhaps an argument can be made that the sculpture serves a purpose by provoking comment, but the same could be said of any pile of debris left by the side of a building. Further, I fail to see how the piece serves as “an interactive window into the geology of our area,” as you state. There is nothing interactive about it, unless you want to argue that the mere act of having your eyes detect the light bouncing off of it is interactive. And it offers no “window in the geology of the area” whatsoever. By the sculptor’s own admission, the mimicry of the region’s geological map, which served as the template for the start of the piece, was quickly lost as the weight of tire strips morphed the shape into a new and unrecognizable form. I could, perhaps, respect the artist’s use of recycled material as a clever statement by her about the nature of the built environment and discarded materials, except that by her own admission she was making no such statement at all; her choice of materials was based solely on the fact that she could get them for free from the recycling center next door to her studio. This makes Solid State Change a powerful work of contemporary art in the exact same vein as a pile of tires on a manure pile at any local dairy farm: you can pretend to find any kind of message you want in it, but there was no such message intended in its manufacture.

I understand that the appreciation of art is subjective, and that tastes will differ. Our opinions about Solid State Change are a case in point. You find it stimulating, and I find it atrocious and an embarrassment for the college. You find that it has primal presence, and I find that it is an eyesore that looks more like abandoned construction debris than art. You think it provides an opportunity to be wowed, and I find it an insult to sculptors who set higher standards for themselves than Ms. Fisher, who has said that the primary purpose of sculpture is simply to “take up space.” You find your frame of reference repositioned in a “new galaxy sort of way” (whatever the heck that’s supposed to mean), and I find myself wondering whether the trustees feel like they got conned by an artist who was looking to make a quick buck. You ask about the sculpture, “What’s not to like?” And I say, “Nearly everything.” If you want to convince me otherwise, you’re going to have to do a heck of a lot better than this.

Steve, thank you for sharing your views on this. It sounds as though you’ve been living with a fair amount of pain these last few years, and it’s obvious that this piece affects you on a very deep and personal level. Art often affects us this way whether we wish it or not. Like so many things in life art challenges us when we least expect it, when we least desire to be challenged. Yet in the challenge lays an opportunity to examine the self and to reaffirm beliefs or overturn them. That sort of opportunity, I would argue, is one of the most important things an academic institution can offer to its constituents. Like a work of art or don’t like it. I have neither the need nor the intention to convince you one way or the other. The choice is up to you, and the entire community is enriched when you share the thought process that has led you to one or the other as you have done here. So if this piece has managed nothing more than to reinforce your aesthetic, then it has served an educational purpose, and that purpose is magnified through your comments.

You did not bother to comment on the various found-object pieces in our current exhibition mentioned in my post. Indeed, I doubt you read the first two-thirds of the post, else you would have understood what I meant by “reposition(ing) your frame of reference in a new galaxy sort of way.” Given your reaction to Solid State Change I can only guess that you will harbor as much disdain for the works in the exhibit as you do for Deborah Fisher’s artwork, yet I would still invite you to view the exhibit in person and share your thoughts with our audience. Those of us who work to present art of all sorts to the public are, I believe, predisposed to harboring some sort of affinity for the works on view, and we benefit when members of the public share their thoughts and feelings about the art whether or not they affirm our beliefs.

Ultimately, the fact that you find this work atrocious is truly a First World problem. There are those for whom discarded debris forms the vast majority of the landscape. They walk across it on their way to and from the destinations that fill their day. Their children play on it. Their children play IN it. The fact that you and I have the opportunity to confront and to find in this piece of recycled art whatever such messages we see—and that we have access to the digital infrastructure that allows us to share our dialogue with the world—is a blessing, an opportunity not to be missed. I’d like to think that the trustees would agree.

Doug, you shouldn’t confuse your role as an administrative operations manager with being a psychologist. The fact that someone finds a supposed work of art to be ugly, as I do Solid State Change, doesn’t mean they have been living in pain because of that object. This would be no more true than me making the claim that someone who waxed rapturously about a work of art was delusional.

What I am, however, is annoyed.

I am annoyed that the artist has been so consistently dishonest in her discussions about the piece, both in terms of its creation and subsequent student reaction.

I am annoyed that the rest of the grounds surrounding the installation cannot be the site of any additional landscaping (such as a flower bed), a stipulation, I have been told, that was placed in the contract by the artist.

I am annoyed that the formal arts community at Middlebury College seems so desperate to justify the piece as being worthwhile that they either describe it in terms that show they actually know little about it (as you did, describing is as “an interactive window into the geology of the region”) or say that its value lies primarily in the fact that it challenges the observer’s views about art rather than any aesthetic appeal.

I am annoyed that no distinction ever seems to be made about the different roles played and effects made by art shown in a museum gallery and art permanently bolted to the side of a building. My views on the items on display in “Environment and Object” are irrelevant. My views on the values of displaying art of any kind depend very much on the nature of the display. In fact, I agree with you that there is value to art that “challenges us when we least expect it, when we least desire to be challenged. … if [it manages] nothing more than to reinforce your aesthetic, then it has served an educational purpose.” But I believe the primacy of this value is conditional. What is useful for an installation in a gallery – where someone chooses to visit on their own terms – is quite different for a permanent installation in a public place where people have their offices and where tour groups walk by.

I am annoyed by the apparent assumption that Solid State Change actually serves an educational purpose. Its installation offers no interpretation, leaving the viewer to take the interpretation “Oh, the college cares so little about its grounds that it left a pile of construction debris next to this building” as valid, unchallenged unless someone actually walks up to the apparent pile of debris and notices the stone label set flush to the lawn.

I am annoyed by the implication that I or anyone else should be satisfied with being confronted by ugliness on a daily basis simply because someone else feels that there is value to us being confronted by ugliness.

I teach a subject other than art, and as part of that, I try to teach students that if they don’t like what they see or experience in the world, then they have the tools, the skills, and the wisdom to make a change. If the arts community at Middlebury College really wants Solid State Change to serve an educational purpose, let us host an event that says “we’ve heard your views that this sculpture is not appreciated here, and therefore we are moving the installation.” That would allow Solid State Change to serve as the focal point for the truly important lesson: change is possible.

And if you wanted the sculpture installed outside of your office, I would support that completely.

ugly, strange, offensive?? how about thought provoking, enlightening

ref: Viyé Diba

kurt, I agree. I think it challenges the mind in a most aggressive way and invites the viewer to update his or her perception of what constitutes art.

Pingback: Nature’s Force: Environment and Object, Recent African Art | MiddBlog