As I watched our preparators put the finishing touches on the installation that now occupies the museum’s upper balcony—four heads by New York artist Richard Dupont, generous and timely loans from a private collection—my mind was overrun with clichés about heads. They shouted at me like kids in the backseat: “get your head around this exhibit” “you’ll have to put your heads together to figure this one out” “heads up!” “head in the clouds, feet on the ground” “head strong” “figure head.” They rolled on, relentless.

Indeed, the human head is a juggernaut of subject matter. It’s where we live. It’s who we are. It’s how we process all that we sense about our world, and it’s the origin of all of our responses to those stimuli. It’s the center of our universe. So the mere sight of a head in an unanticipated context can uncork the flow of visual associations, puns, and clichés that jump so readily to the fertile mind.

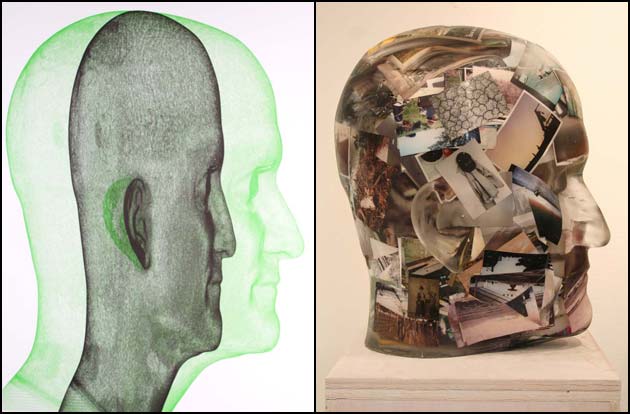

When you get the chance to view this installation in person, you’ll see what I mean. Dupont’s four monumental heads—and they’re his heads, all reproduced either two dimensionally on paper or three dimensionally in cast resin from a high resolution digital scan of the artist’s body—stand guard over the entrance to the Reiff Gallery like the iconic, mystifying heads on Easter Island. And like the Easter Island heads they lead me to ask myself, “What do they mean? What purpose do they serve?”

Of course, Dupont’s heads are anything but clichés, yet they spark associations across the landscape of human thought and memory in much the same way that clichés do. His two-dimensional heads resemble topographical maps, so they’re actually three-dimensional, and like topographical maps they challenged me to parse all of their suggested spatial relations by relying on my own cached, clichéd understanding of topography. His three-dimensional Correspondence Head—full of postcards, letters, and photographs, the detritus from years of hoarding human contact—completes the derivative calculus function posited by the other heads, and just one look flashed me back to a shoebox full of similar hoarding in my own closet. The more I stared at these two- and three-dimensional mesh networks, the more nuanced their forms became, and the more commonalities they seemed to share with my own head. Contemplation of Dupont’s head allowed me to glimpse a common denominator of social consciousness through a sort of cerebral parallax effect, and in the process I came to recognize his tendencies as my own. I saw bits and pieces of myself in him. This reaction is, in part, what the artist intends.

But I don’t want to dwell on the artist’s methodology or his intended meaning within these pieces. There’s plenty of time for you to explore that on your own in the gallery, or you can get a decent amount of it from the press release. What you need to know is much more important than that. What you need to know is that after staring down Richard Dupont for the better part of an hour I was suddenly and unshakably obsessed with heads. So I did the obvious: I wondered around the museum looking for more heads, and only the disembodied ones. Apples to apples.

The two I found in the Lower Gallery startled me at first. Crown Prince Commodus and the Head of a Wounded Amazon, both unassailable in their antiquity, demanded to be read in the context of a complete body as though it were my responsibility as a contemporary viewer to imagine what once was there below the neck and to respect these heads for the mere fact that they alone have survived across the ages. But gradually, like centuries of pretense falling away, they dropped their affectations and allowed me to see their truth—Commodus, that perfectly coiffed head of hair so elegantly framing an imperial aloofness that only a true idealist can wear successfully; the Amazon now retreating into her vulnerability, hoping to live to fight another day. Two heads, vibrant and alive across two millennia, solely for my contemplation in that moment. Stunning.

The two heads in the Cerf Gallery were somehow more readily approachable. Medardo Rosso’s Bimbo Malato, despite the warmth of its patina, felt vacant and unmotivated. Lazy, actually. I wanted to pity him, yet the shallow relief of his face begged me to believe that his condition was not entirely of his own choosing. Rodin’s Pierre de Wiessant, on the other hand, came at me with such fullness of expression that I had no choice but to mistake his self-assuredness for arrogance. His eyes closed, he searched the furthest reaches of his indignation for the patience to tolerate me. Such juxtaposition these two achieve—the Rosso emerging from its material with trepidation and almost faceless pathos, the Rodin fully self-realized with every assertive stroke of the underlying clay a study in confidence. And yet I found myself wanting to believe that these two were simply different sides to the same person, the one suppressing the other, or vice versa, depending on the whim of circumstance. The two as one, perfect in its schizophrenia.

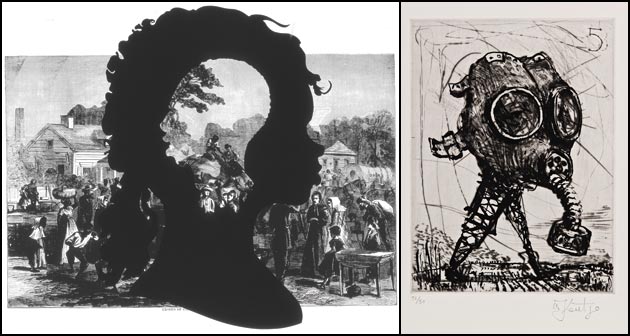

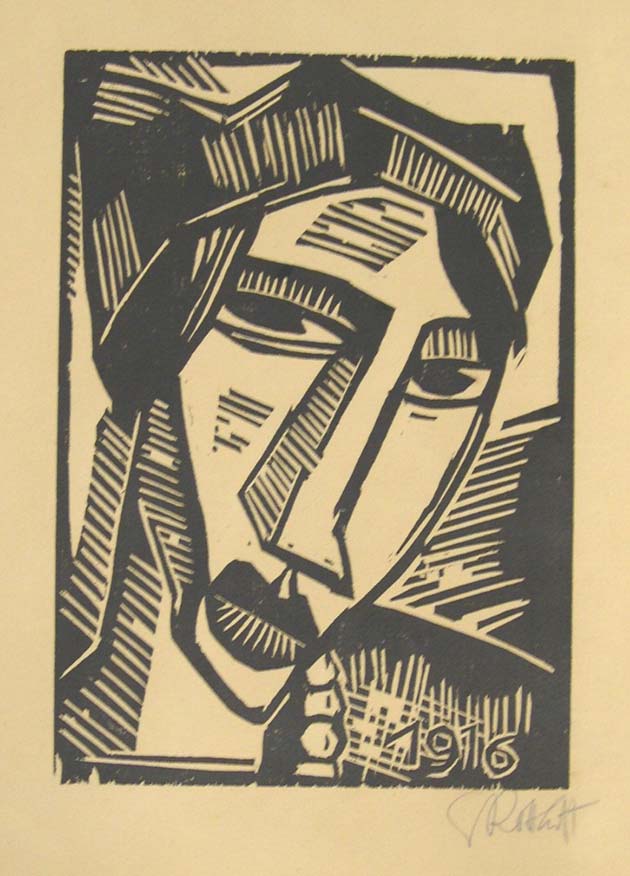

The Overbrook Gallery, currently home to the student-curated exhibit How Did I Get Here? as well as various objects related to this semester’s curriculum, served up no fewer than four heads. Kara Walker’s Exodus of the Confederates, which is actually two heads in one, seemed entirely off-putting, its thick and unpliable social agenda worn like a campaign button for all to see. Regardless, I tried to engage with it, but to no avail. It would not let me get a word in edgewise. William Kentridge’s Mal d’Afrika, however, invited me in to play an active role in its dissention. While Kentridge’s head is technically not disembodied, I could scarcely refuse an invitation from a giant gas mask terrorizing the political landscape atop two inverted oil derrick legs. I was prepared to beg like a five-year-old to honk the horn and control the huge vacuum cleaner nose attachment to dispose of anyone who got in the way. These two works fought over me like two parents in a custody battle, the one telling me that the answers should be clear, the other entreating me to enjoy my own answers. And my own head swelled from the attention until Karl Schmidt-Rottluff’s Woman’s Head glared disapprovingly down her long, angular nose from the other end of the gallery and quipped, “So, this is how you like to live your life?”

Following that (mostly) undeserved comeuppance I tucked tail and ran upstairs to the Painted Metaphors exhibit. There are a lot of heads in this show, including an iguana and a porcupine, but one head called for my attention much more loudly than all the others. The Incense Burner and Lid in the Form of a Deity Head has a primal presence. It does not demand to be worshipped, but it makes clear that there will be consequences for those who do not. It’s more than just a little wild and crazy. And it possessed me like a forbidden instinct. I wanted to dance and speak in tongues. I wanted to drop to the floor and shake out every last drop of crazy, restless, tainted energy. I wanted to exorcise the demons of propriety and find salvation in the embracement of taboo. All of that from staring at a head that cannot stare back. Jinkies!

The most surprising head I encountered, however, was the head that isn’t there. The Edo period Suit of Japanese Ceremonial Armor that lords over the Asian collections from the back corner of the Reiff Gallery reads as a full seated figure complete with gnashing teeth, soul patch, and a startlingly effective mustache, but it does not, in fact, have a head. So it absolutely needed mine to become whole. I was astonished at how readily I was able to imagine saddling myself with the substantial weight of this armor and surveying my domain from a stronghold of gilded bronze. I felt the stability of my posture buttressed against the heft of honor and responsibility. I sensed the constraining bonds of tradition. The room reeked of discipline.

I saw myself in there.

That armor, that head that isn’t there, restored reason to my frantic, scattered search for heads and provided the grounding necessary to return to the balcony and reconfront Dupont’s heads. His Correspondence Head now, an hour later, no longer seemed transparent. I could no longer look into it, nor did I want to. I was too busy projecting my own memories and illusions onto its surface. Parallactic displacement had become mirrored reflection. I had moved from “I see bits and pieces of myself in there” to “I see myself in there.”

And that modified parallax moment actually threatens to blur my identity, because now I’m in Richard Dupont’s head and he’s in mine. I identify so closely with my own head, and yet, if I can see so much of myself when I look at someone else’s head, how can his identity not be mine as well, and vice versa. So then, who am I? What am I? Am I the aloof idealist or the vulnerable warrior? Am I unmotivated and trepidatious or indignant and self-realized? Am I a campaign button? A gas mask? Disapproving? Crazy? Restless? Tainted? Taboo? Buttressed against honor? Constrained by tradition?

I am.

I am what I see when I look into another, and I am the mirror when others look into me. It’s a timely concept, which is why at the outset I referred to these four works as “timely loans.” The world is rife now with conflict and misunderstanding, and yet, when we look at others and see ourselves it all fades away. I am you, and you are I, and the Golden Rule is alive and well.

Richard Dupont’s head told me. Psst, pass it on.

Hat tip to Jeff Inglis ’95 for the “startlingly effective” mustache descriptor.