This month we offer book reviews by three undergraduate students at Middlebury College: Vee Duong, Van-Giang Nguyen and Wengel Kifle.

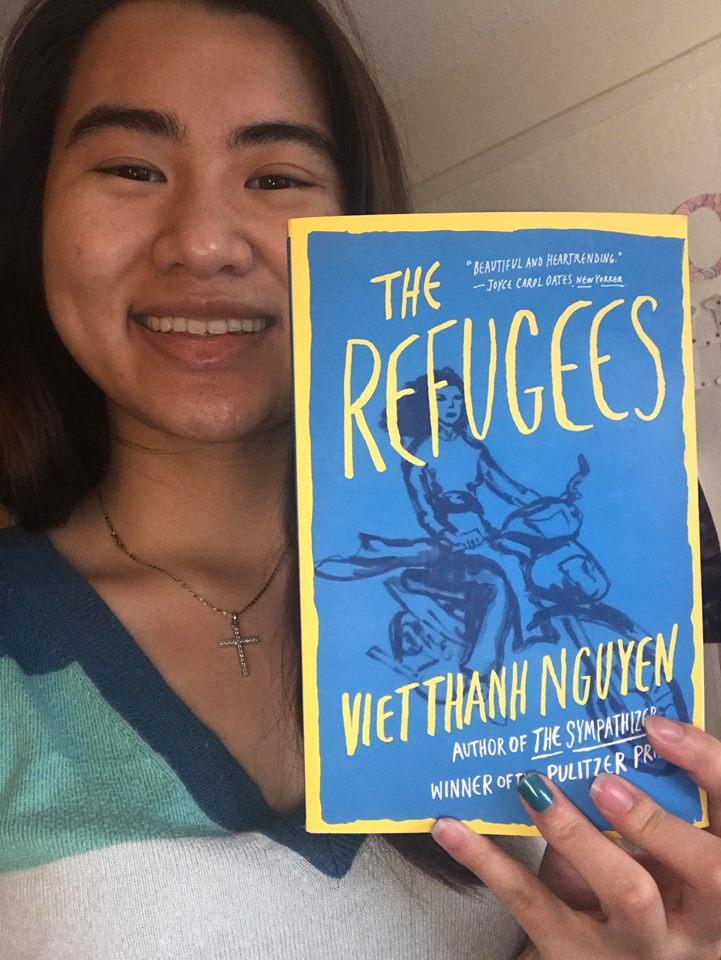

Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Refugees (reviewed by Vee Duong, ’19, Literary Studies major)

I felt many emotions while reading Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Refugees. It was the first time that I had read stories that represented Vietnamese people as more than helpless refugees from a nation ravaged by the Vietnam War (or American War depending on which “side” you are on). The book contains multiple vignettes from the point of view of Vietnamese refugees as well as others who have a relationship to Vietnam. (One is about an American veteran who returns to Vietnam as a tourist.)

It is important to note that none of these vignettes really have a definitive start or conclusion, and I think Nguyen’s choice to structure the stories as such is a powerful statement on the impossibility of capturing the experiences of a refugee – of another human being – in a traditional narrative arc. I think that Nguyen really pushes against the impulse to write refugee experiences as transformative and as a rediscovery of self with the act of being displaced leading to fundamental changes in identity.

As a child of Vietnamese refugees and as someone who grew up surrounded by stories similar to the ones found in Nguyen’s work, I am happy and excited to see these stories finally being told. The narrative of refugees being weak, dependent, unclean, etc., has become pervasive in our current national discourse on immigration. In Nguyen’s The Refugees, we meet a whole cast of characters who embody the wide diversity of refugee experiences, and, at the end of the work, he pens two powerful essays about the importance of looking at the experience of Vietnamese refugees within the historical context of immigration to and from the U.S. I am further impressed that Nguyen does not simply write of the diasporic journey that is so-often at the core of refugee stories. Rather, he beautifully weaves in the past, present, and future of the characters to provide a rich narrative and humanity to his characters.

Nguyen is from Ban Me Thuot, Vietnam which is famous for its coffee and is also my father’s hometown. I visited Ban Me (as my father affectionately calls it) last summer for the first time with my younger sister. It is all-at-once powerful and overwhelming to read Nguyen’s work that tells the story of my parents and relatives and to be able to have conversations with fellow Vietnamese-Americans, with my parents who have their individual refugee experiences as well as with Vietnamese friends who were born and grew up in Vietnam about his work.

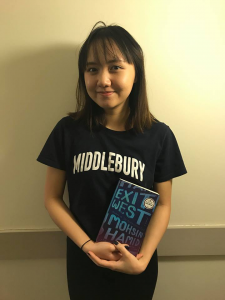

Mohsin Hamid‘s Exit West (reviewed by Van-Giang Nguyen, exchange student, Communication-Media major)

I read this book because one of my good friends recommended it, and I found it to be a compelling and easy read. Published in 2017, Exit West follows the sort-of love story of two characters, Saeed and Nadia, who are forced to flee their home country that has devolved into civil war. Saeed and Nadia flee to various places from their hometown, stopping first at Mykonos, Greece, then traveling to London, U.K., and finally the story concludes in Marin county in San Francisco, California. The story is one of displacement, movement, refugeeism, and the shared humanity of those who are refugees and those who are not. Hamid also tactfully inserts a fantastical element into the plot: magical doors that people can step into and emerge elsewhere.

I felt conflicted about these doors that seemed to be a metaphor for the journey that refugees make in order to leave their home countries. Collapsing the often arduous and dangerous voyage into a mere passing through a doorway erases the physical hardships of the refugee experience in exchange for a more romanticized journey. However, the collapsing of the journey also allows readers to view refugees as much more than simply their voyage. Rather, the voyage is simply one aspect of a refugee’s identity and experience and that the past and future of the person is far more important. I believe that the story is a compelling and easy read because, as someone who is not a refugee, I am able to connect with the characters’ emotions – the sadness of parting, heartache, missing and longing for someone who is far away. In a way, this is both powerful but potentially problematic as readers are able to see the humanity of refugees though are not given a sense of the physical trauma that occurs during the journey, a trauma that most readers who have access to this book would not be able to identify with. Nevertheless, I think the work is thought-provoking and should be one that my peers engage with critically!

A review of nayyirah waheed‘s salt (reviewed by Wengle Kifle, ’20, Political Science major/African Studies minor)

I love waheed’s ability to capture the deepest, rawest emotions of eras and lifetimes into concise poems that hold the depth, the weight and floods of oceans.

waheed writes often of oceans, the moon, and sun, flowers, and honey, and salt. Her poems are enriched by her inclusion of these familiar and natural entities. The refreshing vulnerability of her writing has a way of pulling you out of the distractions and abstractions of society into the self, the spirit, to people, and nature: the real things of a human life.

I read her poems steadily and slowly. Her style is sharp and precise, yet soft and tender. She plucks out the abstractions, like weeds, that society deeply plants within us. Her poems examine notions of masculinity, white beauty standards, colonization and racism. These short accounts offer something so unique with the raw and personal way that they address hard truths. Each of them holds tremendous power and evokes great emotion.

Her poems also cover relationships, families, friendships, childhood, parenthood, womanhood, and manhood. Anyone can find value in these poems, but waheed offers a particularly special place for black women – a sort of therapy.

As a black woman, I have seldom read accounts that I have been able to draw such strong connections with. I relate with many of the poems so profoundly – I have shed tears and broke into smiles reading her poems – and have talked to black women about their similar feelings for the book. I consider this book a safe haven: somewhere I can go to be understood and nurtured. Her book is a place to cry for the pain, the loss, to sit and heal, to forgive one’s self, and to commit to a better, more loving relationship to the self, and this earth.