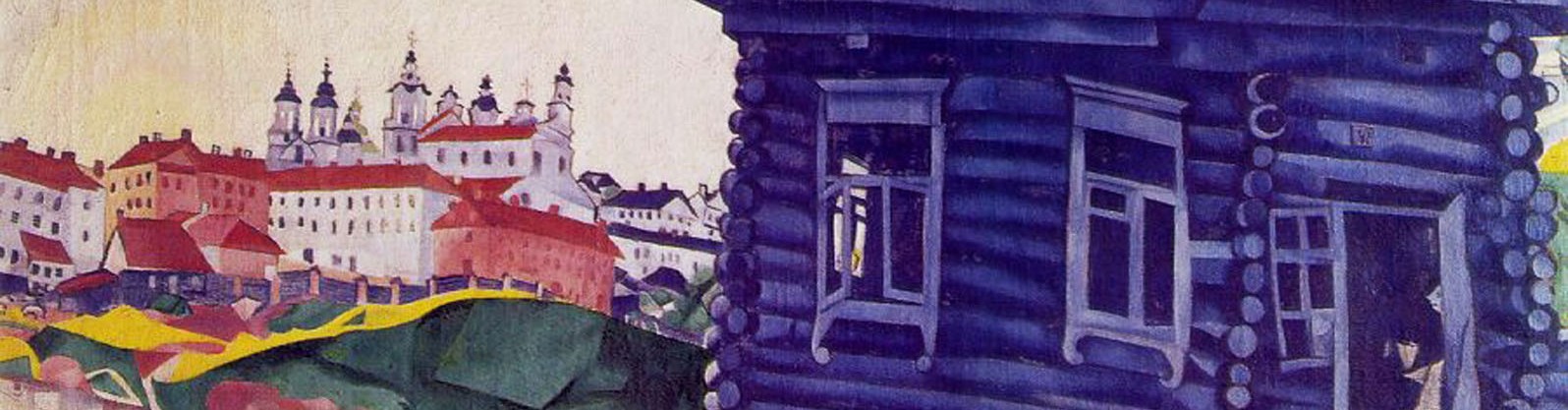

“…Everyone makes mistakes, even God! …Didn’t God Himself make a mistake when He settled the Jews in Russia so they could be tormented as if they were in hell? Wouldn’t it have been better to have the Jews living in Switzerland, where they would’ve been surrounded by first-class lakes, mountain air, and Frenchmen galore? Everyone makes mistakes, even God.” – Isaac Babel, The Odessa Stories, 152

When reading Isaac Babel’s stories, one asks, what sorts of moral struggles do Babel’s characters face, and how does their Judaism confront these struggles? What sorts of problems or questions are they forced to confront about their identity as Jews? It seems that the doctrine many of Babel’s Jews follow is belief, belief, belief over all else – the traditional doctrine. One should believe and hope and trust in God, even when the world around seems dark.

At their core, the dilemmas Woody Allen’s characters confront are the same as Babel’s, even though Allen is a Jewish-American film director with Eastern European roots who is filming after the occurrence of the Holocaust and the spread of secular (or ‘cultural’) Judaism. These are fundamental human problems and questions that are intertwined with belief in God and God’s judgment or religious Truth – questions such as the question of justice or the question of good and evil.

The difference between Babel and Allen lies in the approach and answers to these questions, which have been impacted by the transformation of Jewish identity that occurred in the 20th century. Whereas Babel’s Jews may represent a more traditional approach to Judaism, Allen’s Jews are confronted with the obstacle Fackenheim laid out. They ponder questions about belief and trust in God in a more cynical, skeptical manner; for many of Allen’s characters, Judaism is even possible without belief in God.

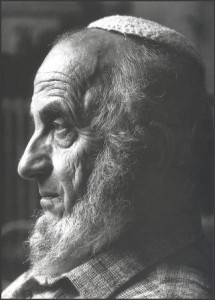

Emile Fackenheim’s argument for a modern interpretation of Judaism contextualizes the themes that run through Babel’s and Allen’s works. Fackenheim argues that the Jewish people have a tumultuous history, expressed through a pattern of ‘last-minute salvation’. The Holocaust was the first time in history when a catastrophe occurred first and salvation followed, rather than salvation halting an impending “radical threat” (Fackenheim, 35). This precedent transformed Judaism, thus, Fackenheim states, “Salvation… came too late, and all that is new… in the contemporary Jewish situation is due to this circumstance.” (Fackenheim, 36) For centuries, belief in Judaism was rooted in “reliable tradition” (Fackenheim, 25). 600,000 Israelites had seen the revelation at Sinai with their own eyes; this fact was enough to preserve faith (Fackenheim, 24). Yet, because of the precedent the Holocaust set, and because of the rise of modern philosophy and science, tradition became a weak basis for legitimacy – a mere “source of historical probabilities” (Fackenheim, 25).

Jews were paralyzed by hope during the Holocaust. They were assured that the Messiah would come. They were assured by the blatant fact of their complete innocence and the complete wickedness of the Nazis (Fackenheim, 268). Yet, God did not come. The St. Louis was sent back, other countries did not intervene, and millions were murdered. Perhaps God lacked power, for He did not bring salvation until it was too late. In the gallows and the gas chambers, God was intimate – He loomed within the pain of his people. God was also infinite, though, for He did not intervene – “He failed to hear the screams of children” (Fackenheim, 289). If one says God was intimate during this time, He appears powerless; if one says He was infinite, He appears heartless. Perhaps He felt such deep empathy for his people that He was paralyzed by it. How could one reconcile the impotent intimacy and “infinite of absolute indifference” of God (Fackenheim, 289)? And how can the implications of this tragedy and this God be reconciled with Judaism today?

The Holocaust did not conform to the traditional teachings of Judaism, for example, that extreme human wickedness would bring the coming of the Messiah. It created conflict and confusion concerning the intimacy and infinity of God, and the place of tradition in Judaism. Jews around the world lost hope and faith as millions of their people lost their lives in Europe. The character of Judaism was transformed after the tragic precedent of the Holocaust. Resolute human action created the State of Israel, because the time had passed to pray and wait. Yet, in this time of human agency, hope became more important than ever. Personal commitment to faith became the best assurance against the destruction of the State of Israel and therefore the destruction of Judaism. After the Holocaust, the fragility of hope and faith were more apparent than ever before. It became imperative, therefore, that Judaism be preserved and protected in the most secure place of all – the soul of the believer.

Bibliography:

Fackenheim, Emil L. What Is Judaism?: An Interpretation for the Present Age. New York: Summit, 1987. Print.