Isaac Babel lived a short and tumultuous life, flooded with questions of his Russian-Jewish identity, numerous love affairs, and above all, the desire for expression. His stories were more often than not built upon autobiographical experiences, from his memories of the pogroms in his childhood to his time serving in the Red Army. The tension between the individual and his inner world pitted against the surrounding environment permeates Babel’s works, for this was a tension he faced throughout his life. (Rubin, 10)

Isaac Babel lived a short and tumultuous life, flooded with questions of his Russian-Jewish identity, numerous love affairs, and above all, the desire for expression. His stories were more often than not built upon autobiographical experiences, from his memories of the pogroms in his childhood to his time serving in the Red Army. The tension between the individual and his inner world pitted against the surrounding environment permeates Babel’s works, for this was a tension he faced throughout his life. (Rubin, 10)

Babel left behind few traces of his life and work. What is worse, many of those books and autobiographical facts that he left behind have been heavily edited or are pure misinformation or rumor. It is important to keep in mind the time in which Babel was writing. He was a passionate, outspoken Jewish author, who was active in an ultra-censored, cautious country directed by an iron ideology and ultimately controlled by a brutal dictator.

Thus, Babel’s books, letters, drafts and unpublished manuscripts were destroyed after his execution. In addition, according to the Babel biographer Patricia Blake, Babel “failed…to take precautions to preserve his unpublished work” (Blake, 3). Furthermore, many of Babel’s works that are available today were “corrupted by censorship” (Blake, 4). Facts float around that are rumored to be true, but cannot be verified. One such fact, apparently claimed by Babel himself, is that he worked for “the Soviet Secret Police from October 1917 to 1930”. This is a strange claim, considering that the NKVD “was founded in August 1917” (Blake, 5).

The below chronology is based on facts gathered from multiple notable Babel biographers. I have included various rumors within the chronology and have demarcated them as such. Although much of what we know about Babel may be untrue, I believe it is still important to take rumors into account, for a grain of truth may lie within them.

Childhood:

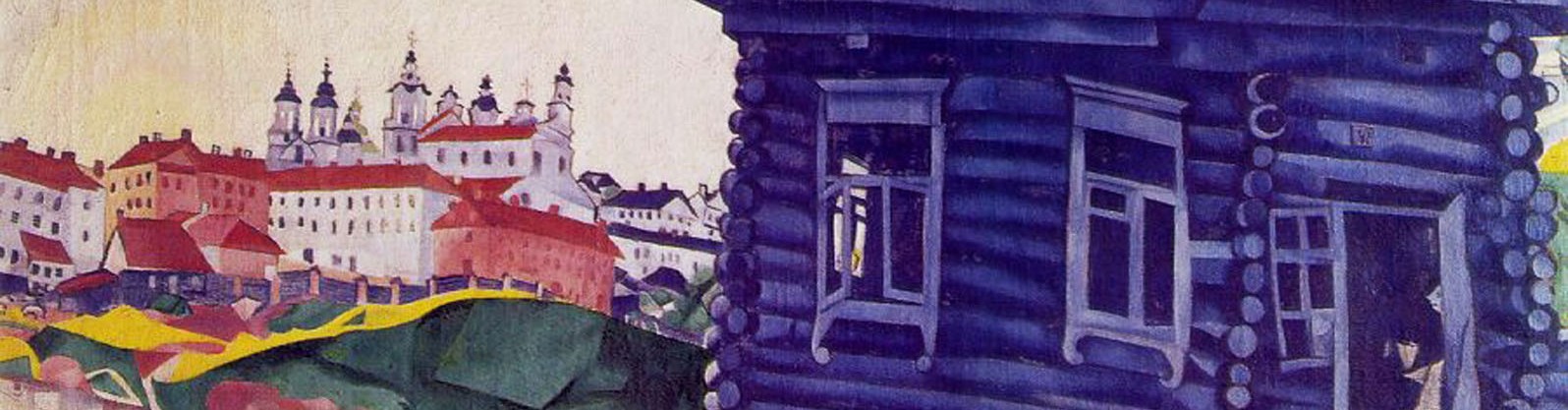

- 1894: Born on June 30 1894 in Moldavanka, a poor region near Odessa

- At a young age, he begins an extensive education that included English, French, and German, and private Hebrew lessons.

- 1905: Yet, Babel did not and could not live the sheltered life of a student. The town to which his family moves, Nikolayev, faces pogroms in 1905. Many of Babel’s stories, especially those told from an innocent child’s point of view, are inspired by this raw reality.

Student Life:

- 1911: He attempts to enter the University of Odessa in 1911, but is rejected because of quotas on Jews. (Freidin)

- Instead, he enrolls in the Institute of Finance and Business Studies in Kiev. It is here that Babel wrote his first story, Old Shloyme, and meets his future wife, Eugenia Borisovna Gronfein. (Freidin)

Young Adulthood:

- 1916: In 1916, Babel graduates university and re-locates to St. Petersburg. There, he meets Maxim Gorky, a writer and political activist. (Freidin)

- Babel contributes sketches and stories to Gorky’s political, literary, and scientific journal Letopis (Летопись). The journal brings together authors philosophers who oppose nationalism and Wo

rld War I. (Zakharova)

rld War I. (Zakharova) - 1917: Babel volunteers for the Red Army on the Rumanian front for a short time. He fights alongside “uneducated Cossacks” and serves “under Commander Budenny”, both of who are infamous for initiating pogroms against Jews. (Rubin, 10)

- In November, he returns to Odessa, where he decides to take the dangerous trip to Petrograd. (Freidin)

- Once Babel reaches Petrograd, he joins the Cheka for a brief period, acting as a translator for their counter-intelligence department. (Freidin)

- 1918: Babel authors numerous sketches that were published in Maxim Gorky’s anti-Leninist newspaper, Novaya Zhizn. This publication is then closed on August 6th. (Freidin)

Authorhood:

- 1920: The Odessa Party Committee grants Babel the title of war correspondent. He is given the codename Kiril Vasilevich Lyutov. Babel is to spend the months of June through September on the Polish front with with Commander Budyonny’s Cavalry Army. (Freidin)

- 1923: Babel publishes many of his famous Benya Krik stories. (Freidin)

- 1923-24: Babel spends these years writing his Red Cavalry stories, influenced by his time on the front. (Freidin)

- 1925: Babel publishes his first two stories from the child’s point of view. (Freidin)

- 1925: Babel’s wife Eugenia moves to Paris. (Freidin)

- 1925-1927: Babel has an affair with Tamara Kashirina. Their child, Mikahil, is born in July 1926. (Freidin)

- 1926: Red Cavalry is published. Once these stories are published in English, Babel acquires international fame. (Freidin)

- Commander Buddyony takes issue with the stories upon their publication. He continues to criticize and attack Red Cavalry for the rest of the 1920’s. (Freidin)

- 1927: Babel writes a film script for Benya Krik. The film is quickly removed from circulation after its release. (Freidin)

- 1927: Babel has a brief affair with E. Khaiutina, the future Mrs. Nikolai Yezhov. He then travels to Paris to see his wife. (Freidin)

- 1929-30: Months after the the publication of Red Cavalry, Babel is criticized by Soviet authorities for inactivity. Thus, Babel journeyed to Ukraine in order to find inspiration for his stories. He is struck by the horrors of famine and collectivization. (Freidin)

The Beginning of the End:

- 1930: Babel is charged with giving an anti-Soviet interview to a Polish newspaper. He denies the interview, claiming that it was a fabrication. His requests to return to Paris are denied. (Freidin)

- 1931: Babel resumes communication with E. Khaiutina. During this time, it is said that Evgeniia Solomonovna called “Babel three or four times a day during the Great Terror – or, more pertinently, during the Ezhovshchina – and waited for him outside his apartment in her chauffeured limousine.” (Blake, 7)

- 1932: Babel is acquainted with Antonina Nikolayevna Pirozhkova, his second wife. They travel through the Caucasus in late 1932-33. (Freidin)

- 1932-33: Babel is allowed to return to Paris. (Freidin)

- 1934: At the First Congress of Soviet Writers, Babel openly wages criticism against the cult of Stalin. (Freidin)

- 1935: Babel “establishes a household” with Antonina Nikolayevna Pirozhkova in Moscow. Their daughter, Lida, is born in 1937. (Freidin)

-

1936: Nikolai Yezhov takes Genrikh Yagoda’s position as NKVD head.

- 1938: NKVD head Yezhov is replaced by Lavrenty Beria. After Yezhov’s arrest, he gave evidence that was used to indict Babel.

- 1939: On May 13, Babel is arrested under the charge of spying for France and Austria. This charge was supported by testimony from Yezhov as well as two writers, Boris Pilnyak and Mikhail Koltsov. Apparently, Babel was arrested on the same day as former NKVD chief Yezhov’s wife, whom Babel also happened to have an affair with. (Blake, 5)

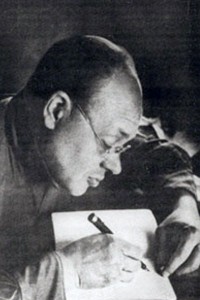

- 1940: Babel is executed in Lubyanka prison on January 15. (Freidin)

- 1948: There are rumors about Babel’s release from prison. (Freidin)

- 1954: Babel is exonerated; his death certificate states that he died of unknown causes in 1941. His death certificate was “set forward fourteen months.” (Freidin)

- According to Patricia Blake, falsifying the death date of a victim was a normal practice, done to conceal the fact that thousands were killed in the short span from 1937-38. Placing Babel’s death at 1941 caused it to appear as though he “died of natural causes over 10 years” (Blake, 8).

Bibliography:

Blake, Patricia. “Researching Babel’s Biography: Adventures and Misadventures.” The Enigma of Isaac Babel: Biography, History, Context. By Gregory Freidin. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2009. 3-16. Print.

Freidin, Gregory. “Isaac Emmanuilovich Babel: A Chronology.” (https://web.stanford.edu/~gfreidin/Publications/babel/babel_chrono_norton01.pdf) 10 Feb. 2001. Web.

Rubin, Rachel. “Introduction: Reading, Writing, and the Rackets.” Introduction. Jewish Gangsters of Modern Literature. Urbana: U of Illinois, 2000. 1-25. Print.

Zakharova, M. V. “Letopis (The Chronicle), journal.” Saint Petersburg Encyclopedia. (http://www.encspb.ru/object/2855694137?lc=en) Web. 10 Oct. 2014.