“A well-thought-out story doesn’t need to resemble real life. Life itself tries with all its might to resemble a well-crafted story.” – Isaac Babel, “My First Fee” (478)

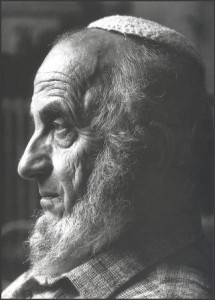

Isaac Babel and Woody Allen lived one hundred years apart in countries that are like day and night. Yet, both are creative geniuses that personalized their respective medium using the language of autobiography.

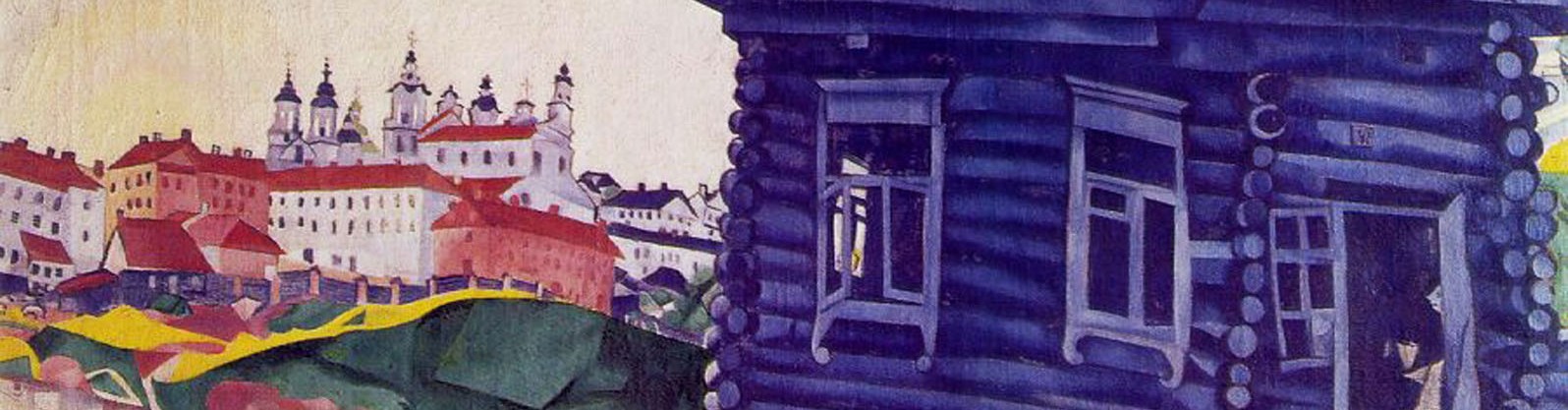

Isaac Babel’s stories were based on his own experiences as a Jewish boy in a frighteningly anti-Semitic society, as well as his experience volunteering for the Red Army. His stories of his childhood perfectly capture young Babel’s interpretation of the world – the small world of the child is juxtaposed with the greater emotional state of the universe. The world around Babel continues to live and breathe although Babel himself may be plunged into despair. It is interesting to note that traces of Anton Chekhov can be seen in the relationship between the insignificance of the individual and omniscient, all-encompassing nature. Compare the two passages below, one from Babel’s The Story of my Dovecot and one from Chekhov’s Gusev:

“This world was tiny, and it was awful. A stone lay just before my eyes, a little stone so chipped as to resemble the face of an old woman with a large jaw. A piece of string lay not far away, and a bunch of feathers that still breathed. My world was tiny, and it was awful. I closed my eyes so as not to see it, and pressed myself tight into the ground that lay beneath me in soothing dumbness. This trampled earth in no way resembled real life, waiting for exams in real life. Somewhere far away Woe rode across it on a great steed, but the noise of the hoof beats grew weaker and died away, and silence, the bitter silence that sometimes overwhelms children in their sorrow, suddenly deleted the boundary between body and the earth that was moving nowhither. The earth smelled of raw depths, of the tomb, of flowers. I smelled its smell and started crying, unafraid.” – Isaac Babel’s The Story of My Dovecot (609)

“The sailor on duty lifts the end of the board, Gusev slides off it, plunges head first, somersaults in the air, and – plop! The foam covers him, and for a moment he seems to be shrouded in lace, but the moment passes and he disappears beneath the waves.

He descends quickly to the bottom. Will he go all the way? … After he has traveled about eight to ten fathoms, he starts going slower and slower, rocking gently from side to side as if deliberating…

And now on his journey he meets a shoal of little pilot fish. When they see the dark body, they stop dead in their tracks, then they suddenly all turn round and disappear…

Then another dark body appears. It is a shark. It glides underneath Gusev grandly and nonchalantly, as if not noticing him, and Gusev lands on its back… The shark teases the body a little, then nonchalantly places its mouth underneath it, carefully grazes it with its teeth and the sailcloth is ripped along the whole length of the body from head to toe; one of the weights falls out…

But meanwhile up above, clouds are clustering together over where the sun is rising, one cloud is like a triumphal arch, another like a lion, a third like scissors…A broad green strip of light emerges from behind the clouds and stretched out to the middle of the sky…” – Anton Chekhov’s Gusev (57)

Babel is able to capture the intense depth of feeling within his own world by piecing together the most minute details – the reader remembers the overwhelming claustrophobic heat and darkness of his grandmother’s home in At Grandmother’s:

“Everything seemed uncanny at that moment and I wanted to run away from it all, and yet I wanted to stay there forever. The darkening room, Grandmother’s yellow eyes, her tiny body wrapped in a shawl silent and hunched over in the corner, the hot air, the closer door, and the clout of the whip, and that piercing whistle – only now do I realize how strange it all was, how much it meant to me.” – Isaac Babel’s, At Grandmother’s (49-50)

Babel also writes on the role of art in his life and the effect that the all-consuming desire to write had over him. Characters in his stories often cannot stop themselves from telling grandiose tales, as if to compensate for the disillusioning difference between their reality and the stories that they create in their minds. These characters are also often incapable of putting their stories on paper. This sentiment perfectly captured in the following excerpt of Babel’s short story My First Fee:

“O Gods of my youth! Five out of the twenty years I’d lived had been spent gone into thinking up stories, thousands of stories, sucking my brain dry. These stories lay on my heart like a toad on a stone. One of these stories, pried loose by the power of loneliness, fell onto the ground. It was to be my fate, it seems, that a Tiflis prostitute was to be my first reader. I went cold at the suddenness of my invention, and told her the story about the boy and the Armenian.” – Isaac Babel’s My First Fee (174)

In a similar manner, Allen either plays in his own films or creates characters that are based on questions and experiences from his own life. The most common Allen persona is known as “nebby neurotic” (the ‘little man’) or the “WASP schlemiel character” (Meade, chapter 2). The persona mirrors Allen’s real inner life: he constantly displays “a compelling existential angst” and a “profound sense of guilt”. Allen’s little man is the “image of a man eternally bewildered by a hostile universe” (Desser, 93).

Although it is an accepted fact that Allen incorporates his life and outlook into his art, it is also known that he strives to maintain privacy and anonymity in his daily life. He does not often give interviews. Still, caricature-esque details about him are well-known, such as that he “eat(s) at Elaine’s or play(s) jazz clarinet.” (Desser, 37)

When an artist lives for the sake of his art, and his art is autobiographical, one has to wonder how much of the human experience he is really capturing in his work. Is the artist merely an actor in his own play, or does he lead an existence detached from his art which then influences the content of his creation?

And what about the viewer or reader, who, knowing that the artist’s work is autobiographical, attempts to relate the artist’s work to the practical world rather than allowing it to exist in the world of art. This attempt has dangerous effects – subjecting characters in the world of art to reality is simultaneously subjecting ourselves to an ideal that we cannot hope to fulfill. Art has an intoxicating quality that lures it to gravitate in simultaneous accord and discord with life. This union, which brings pleasure and pain, is what we may fall prey to after watching Allen’s films or reading Babel’s novels; and it is what both artists themselves attempted (or attempt) to explore through mirroring art and his life.

“The illusion which exalts us is dearer to us than ten thousand truths.” – Alexander Pushkin, The Hero, II.

Bibliography:

Babel, Isaac. “At Grandmother’s.” The Complete Works of Isaac Babel. Comp. Nathalie Babel. Trans. Peter Constantine and Cynthia Ozick. New York: Norton, 2002. 43-47. Print.

Babel, Isaac. “The Story of My Dovecot.” The Complete Works of Isaac Babel. Comp. Nathalie Babel. Trans. Peter Constantine and Cynthia Ozick. New York: Norton, 2002. 601-612. Print.

Desser, David, and Lester D. Friedman. “Woody Allen: The Schlemiel as Modern Philosopher.” American-Jewish Filmmakers: Traditions and Trends. Urbana: U of Illinois, 1993. 37-101. Print.

Meade, Marion. The Unruly Life of Woody Allen: A Biography. New York, NY: Scribner, 2000. Print.