I Live Here: A Reflective Artifact Project

2April 1, 2013 by Tom McKenna

Kim Masterson teaches at Salem High School in Salem, MA. She graduated from Bread Loaf’s Asheville campus in 2007, where she worked for three years as a Director’s Assistant. This summer, Kim will be working at the Vermont campus in the same capacity. Kim credits Professor Tilly Warnock’s Bread Loaf course, “Rewriting a Life: Teaching Revision as a Life Skill, ” as helping her to find the stance she describes in “I Live Here: A Reflective Artifact Project.” Kim’s students’ eloquent comments about the project are captured in two videos at the end of this article.

Ariella, a student in my Honors IV English class, mounted the only picture she owned of her birth mother in the bottom corner of a white piece of paper and typed the words, “so close yet so far” at the top. She told us that she loved her mother, even though Ariella didn’t know her, and that looking at the picture made her feel closer to the woman who gave her up shortly after she was born. Ariella shared this story with us in November, two months after the school year began and four months after I drafted “I Live Here: A Reflective Artifact Project.”

In part, the idea was a product of the short time I spent in a PhD program studying ritual and secret revealing in popular American culture. The assignment asks my seniors to  select a different artifact every month, from some point in their lives, and to reflect on that physical object visually and through language. Revealing secrets is never mentioned. Although I thought the project was creative, Ariella made me realize that the grace, compassion, and generosity with which my students would interpret my directions would far exceed any expectations I held. Often meticulously and lovingly completed, the students’ visual presentations masked painful stories that lay beneath the artifacts.

select a different artifact every month, from some point in their lives, and to reflect on that physical object visually and through language. Revealing secrets is never mentioned. Although I thought the project was creative, Ariella made me realize that the grace, compassion, and generosity with which my students would interpret my directions would far exceed any expectations I held. Often meticulously and lovingly completed, the students’ visual presentations masked painful stories that lay beneath the artifacts.

At the outset, I knew that the containment of the project would be important to help my students feel safe in revealing whatever they desired, so as a policy, we agreed to ask no questions during presentations. Almost a year after beginning the project, Edward taught me that the ritual provided the freedom and the safety for my seniors to express not only what they desired, but also what they felt they needed. Edward rarely came to class. When he was eight, his mother’s boyfriend murdered her in front of his sister. Edward tattooed his arms with his mother’s name, her birth and death dates, roses, an angel, and a cross. He told the class, “The tattoos are a way to always have her with me, have her by my side.” He spoke about her months before her killer was retried on a technicality the man discovered after years of studying his case in jail. Edward wrote “I Live Here” in response to the newspaper articles about the murder and then showed us his tattoos. He said they served as both his artifact and his written reflection, a permanent marker of his loss, his pain, and his memory of his mother.

This moment was one of the most difficult in my room. The students were angry for Edward and wanted to speak out, but they remembered we did not deconstruct or analyze another person’s experience or object. Instead, we gave Edward the space he needed to voice his feelings by keeping our stuff to ourselves. Once he finished talking, Edward sat down, I thanked him for sharing his experience, and we continued  with the rest of the activities for the day. When reflecting about how the project changed his relationships with his classmates at end of the year, Edward told me, “It was good to know it was more than just the friendship I had with them. They’re basically…my family.” We allowed him to say what he wanted and then to leave it – without interjection.

with the rest of the activities for the day. When reflecting about how the project changed his relationships with his classmates at end of the year, Edward told me, “It was good to know it was more than just the friendship I had with them. They’re basically…my family.” We allowed him to say what he wanted and then to leave it – without interjection.

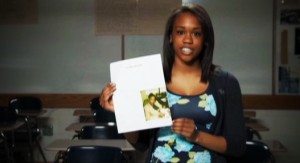

Some of my students feel unable to speak openly about their experiences in the classroom, but I have built into the assignment different venues for expression. In my second year working with the project, Sophie was one of those students who would talk about her artifact with the two or three people sitting near her, but never with the larger group. She, at four, lost her mother to cancer. During her year in my room, she reflected about her mother almost every month. Sophie’s work included journal entries written by her when she was seven or eight years old, photographs of her mom, and lists that her father created of the people who formed a new safety net for Sophie, for her older sisters, and for him. Even though Sophie did not present in class, she let me hang up her work each month outside of my room.

Sophie also wanted to present her project with twelve of her classmates to the School Committee – where members of a select group, at the request of the Committee, share their work as a way to remind the members whom they are serving and why. She told me it was important for her to speak about her mom. She needed the act of giving voice to her mother’s death to work through and to release the stories she carried for years. When we practiced for the meeting in my classroom, her nerve failed. She cried and left. She couldn’t catch her breath, and she couldn’t come back into the room until the other students found her and hugged her.

At the meeting, Sophie again walked out, but we had worked out a plan that afternoon. Jake, who often played the tough guy, would read the journal entries while Sophie stood next to him. Reading  Sophie’s work out loud softened Jake’s attitude. To speak for her, he had to be completely present, he had to help her carry and convey her story. Jake felt the weight and the importance of his actions that day in a way I alone could not have taught him. The day after the School Committee meeting, Sophie completed her last I Live Here project, and wrote, “I felt like I had no one. Well, yesterday I found out I have everyone. I cried. A lot. It was sad. But then I realized these people do care…they’ve been here for me all along.”

Sophie’s work out loud softened Jake’s attitude. To speak for her, he had to be completely present, he had to help her carry and convey her story. Jake felt the weight and the importance of his actions that day in a way I alone could not have taught him. The day after the School Committee meeting, Sophie completed her last I Live Here project, and wrote, “I felt like I had no one. Well, yesterday I found out I have everyone. I cried. A lot. It was sad. But then I realized these people do care…they’ve been here for me all along.”

When I told the class that my husband would be coming to the school at the end of the year to create a video about the project and my students, Sophie expressed her desire to be a part of it. We talked about her reasons for trying again. We also talked about what it means to cry, but to stay in the moment, and to speak through those tears. In the video, Sophie did cry, but she also told her story, and in doing so, shared the memory of her mother with us. Sophie told me that the support she received from others helped her to find the confidence and peace to talk about her mom without running away. She knew we were there with her, and for the first time, she permitted others to help her carry the memory and the death of her mother.

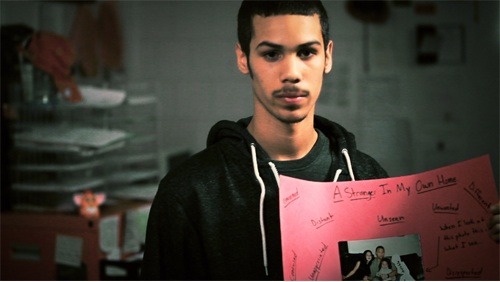

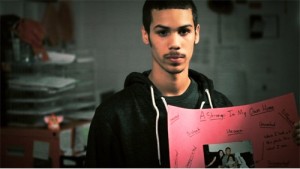

Each month when I hang up new projects in the hallway, groups of students pause to read them with a kind of thoughtful silence expected at an art gallery. Reading the work in the hallway was how my students learned about Alvin. On most days he completed his work, but kept entirely to himself.  Halfway through the year, he turned in a photo of his family mounted on a red piece of construction paper. He glued white paper over the shape of his body and wrote about how he felt disconnected and invisible at home. Alvin did not want to speak about the photo in class, but he allowed me to hang his work up in the hallway. He, too, wanted to take part in the video because, alone in the room with my husband, he thought he could find the words he lost in front of his peers.

Halfway through the year, he turned in a photo of his family mounted on a red piece of construction paper. He glued white paper over the shape of his body and wrote about how he felt disconnected and invisible at home. Alvin did not want to speak about the photo in class, but he allowed me to hang his work up in the hallway. He, too, wanted to take part in the video because, alone in the room with my husband, he thought he could find the words he lost in front of his peers.

More than with any other project, students expressed surprise about Alvin’s story once they saw it. Brion, who grew up with Alvin, told me he spent time at Alvin’s house with Alvin’s parents. Brion said he never knew that Alvin felt so isolated. Brion’s word choice about Alvin’s feelings mattered. He heard Alvin’s story without judging his feelings and without analyzing the behavior of his parents or his understanding of his home life. As in Brion’s experience with Alvin, the move away from judgment to close listening created the space for many of my students to become aware of the lives of others and, in turn, their own lives, just as they were.

The last phase of the assignment asks every senior I teach to select one of their own projects to display at an event I organize in town. Each student writes a sentence or two about the project and about his or her post high school plans. In addition to family members, students invite two teachers with handwritten notes. The teachers rarely decline. At the exhibition, I meet parents who never attended parent-teacher conferences, who never responded to an email. Friends of the students I teach stay for the evening, witnessing the stories of people with whom they grew up, people whom they thought they knew. My seniors’ confidence and compassion, based on mutual respect and a shared understanding of the stories each person carries, electrify the air.

Because of the response of my students and the community, some of my colleagues have asked to replicate the assignment in their classrooms. The request feels complicated to me. The project is incredibly personal, and each of my related actions and responses to students is exacting. In forming my own theoretical stance as a teacher, I’ve spent years working through my own stories and thinking about the nature of revealing. The power results from my ability to turn over the assignment completely to my students because I already mindfully completed the work in my life. My hope is to inspire interested teachers to develop an approach to writing projects that feels right to them, and that may embody the same kind of compassion, respect, and honesty.

By writing and thinking about themselves in a way that felt truthful, and in an environment that felt safe, my students improved as writers. All of our seniors are required to write a Senior Thesis, which is a literary analysis. Because of their work with the “I Live Here: A Reflective Artifact Project,” they were more willing to trust me and to trust others as they explored their analytical voices. My students’ peer editing became more detailed, their academic conversations about writing became more direct, and their ability to explore challenging ideas in texts and challenging writing styles became more nuanced. Understanding the complexity of feelings opened them up to understanding the complexity of language and the importance of writing in many genres.

The students’ remarkable growth affirms my belief that when writers are deeply engaged and believe their readers are to be trusted, they draw on linguistic resources that aren’t available with less personally significant assignments. As a community of writers, we built trust by listening carefully, by caring enough to give each other the space to share and to contain hard stories, and by staying in the moment with each other, even when staying felt uncomfortable.

I wrote “I Live Here: A Reflective Artifact Project,” but the assignment always belonged to my students, from the minute I typed the first word of the directions on the page. The work they produce and their willingness to openly communicate deeply personal stories continues to astonish and to humble me. One of my seniors described the experience best when her friend wanted to present, but initially failed to find the words. She looked her friend right in the eye, touched her arm and said, loudly enough for the class to hear, “Don’t worry, girl. There ain’t no strangers here.” That’s the lesson, exactly.

Watch the “I Live Here: A Reflective Artifact Project” videos, produced by Scott Masterson at Old Harbor Productions:

I LIVE HERE 2011

I LIVE HERE 2012

Category Archives, BLTN Teachers, Fall-Winter 2012 | Tags:

I think more and more that life-story work in writing classes is the only way for teachers and students (administrators, policy makers, and others) to see each student’s full humanity or to imagine each student’s potential. By humanity, I mean what Kim has suggested: compassion, respect, honesty, and empathy, too. We aren’t asked to actively or formally measure these things in any classroom setting, yet they tell us a tremendous amount about who these kids are and what motivates them. While digital landscapes have made the world smaller and have started closing the access gap for some, among other things, the landscapes have also made it possible for web-users to operate under a complete guise of anonymity. Connecting authors to their own stories and those stories to other known authors in their own time and place, I believe has implications for the way our culture assigns worth to the contributions of young people. Beyond that, this type of work has the potential to strengthen students’ abilities to analyze primary texts, to find primary texts, to see themselves and their peers as resources, to imagine futures where they may approach authors to find out more about circumstances (though this project intentionally did not include additional group questioning or analysis), and to address the common core standards, which are guiding curriculum development.

Kim, this piece is poetic in every way, down to the punctuation and you have beautifully woven your reflections on this project into the raw stories of these students, while elevating language in a way that pushes this to that contested space between practitioner and theoretical reporting. The contested space has growing importance for teachers everywhere and nothing makes that argument more clear than this engaging and thoughtful article.

Lillian, thank you so much for your thoughtful and thought-provoking words. In a way that is difficult for me to convey completely, the project certainly has changed the atmosphere in my classroom and that has resulted in so much of what you describe happening as my students’ ability to write and think critically has improved, and as they learn to trust themselves and each other.

In writing, it was my hope to ride that space between practice and theory because our students deserve, at the very least, that. I am so glad that my effort to preserve the integrity of my students’ stories was apparent as I attempted to convey what happens in the room.