[youtube pG41xDxrzI8]

Stunning news! Not really surprising though (nor necessarily encouraging), but here it is. In the most recent bulletin by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), issued at the time of writing (Monday, November 21, 2011), data show a steady increase in the amount of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the atmosphere (PDF). At present, we are at 389 parts per million (ppm) of atmospheric CO2, the highest recorded in the past 10,000 years.

At present, this is substantially higher than the 350ppm hoped for by 350.org, a transnational science and advocacy network, but still within the range deemed acceptable by the Fourth Assessment Report (AR-4) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – namely 350 – 400ppm, as described in their Summary for Policymakers (PDF). For clarity’s sake, this is the range in which most scientists feel we have the best change at stabilizing the projected increase in global temperatures at 2 degrees above the current average. Further, as indicated in the bulletin, it is assumed that the 350 – 400 CO2 level would correspond with a similar leveling of other GHGs, such as methane, sulfur hexafluoride, and nitrous oxide, such that we would have a total accumulation of 445 – 490ppm of CO2 equivalent.

Hot Like Fire

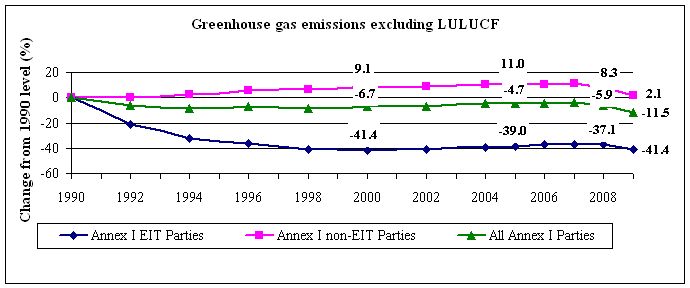

It goes without saying that, even if we took the slightly-less-alarmist AR-4 as the better predictor, we would still be in dire straits. To get to that level, we would need to cut global emissions by 50% – 85% of 2000 levels. Further, this assumes that we would not dramatically raise the amount of other GHGs in the atmosphere. While CO2 is usually held up as the bad boy of the atmosphere (and is currently responsible for about 70 – 80% of current anthropogenic warming), data held by the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) show that the other GHGs are more powerful warmers, based on ppm, than CO2. (This is due to their longevity, as well as chemical makeup). Unfortunately, these show no sign of decreasing and some, like HFCs, are increasing at alarming rates.

Theoretically, we still have time to act. Politically, engendering the will to do so is another question. Part of this depends on our disposition to alarming data – will these trends cause apathy, alarm, or disdain? We don’t know to a certainty what all this means, but the problem is too many people take this to mean we don’t know anything. One way or the other, we’re going to find out. We are, after all, to borrow from Roger Revelle, “…carrying out a large-scale geophysical experiment” with the atmosphere. I suppose that, for those skeptical about climate science theories, the logical thing to do is to take the experiment to its conclusion.

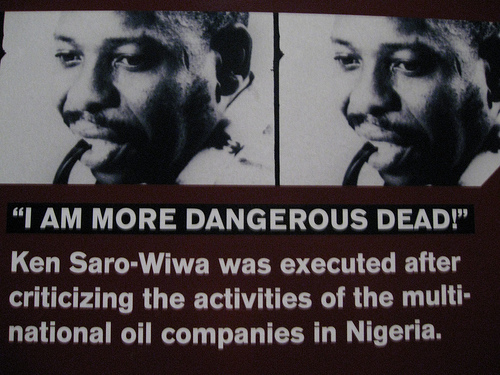

In the 1990s, oil exploration in Nigeria was a travesty of environmental injustice. In the Nigerian Delta, the practice of extraction was incredibly dirty – oil spills, and gas flaring devastated the local environment, and displaced residents. Moreover, the federal government of Nigeria monopolized the control of national oil wealth, giving a disproportionately low share to the residents of states in which oil exploration was taking place.

In the 1990s, oil exploration in Nigeria was a travesty of environmental injustice. In the Nigerian Delta, the practice of extraction was incredibly dirty – oil spills, and gas flaring devastated the local environment, and displaced residents. Moreover, the federal government of Nigeria monopolized the control of national oil wealth, giving a disproportionately low share to the residents of states in which oil exploration was taking place.