Political scientist Lynn Vavreck posted an interesting New York Times column a couple days back in which she noted that midterm elections – more so than presidential elections – are referendums on the president and his party. As she writes, “Instead of rewarding or punishing the incumbent president for his handling of the nation’s economy, in midterm years voters address the president more directly — by penalizing his party members, on average, but also by calibrating that punishment based on how the president is doing his job. Average approval ratings of the way the president is ‘handling the job’ explain more of the variation in seat loss than the economic indicators.”

What Vavreck is referring to is the well-known “midterm” loss phenomenon which I have written about on multiple occasions. Briefly, as political scientists have documented, the president’s party on average loses about 28 House seats and 4 Senate seats in midterm elections during the post-World War II era. There are several explanations for why this is the case, but Vavreck cites one – the “surge and decline” thesis that points to differences in the size and composition of midterm elections versus presidential elections as a primary reason why the president’s party does less well in off-year elections. Strictly speaking, of course, the surge-and-decline thesis is not necessarily a referendum on the president’s performance so much as a fundamental aspect of turnout differences. Historically, as this chart indicates, midterm turnout in recent years hovers at about 40% – these are the habitual voters who turn out every election, whereas in presidential elections we see more variation and usually higher turnout. (This data is from Michael McDonald’s site.)

In 2010, turnout was about 41% of eligible voters, but it was about 58% in the 2012 presidential election.

But, it is also the case that beyond simple turnout factors, midterms are also directly referendums on a president’s performance. From this perspective, how one votes in the midterm is a direct reflection of a voter’s attitudes toward the President. As I’ve discussed in previous posts, congressional candidates – as strategic actors – are very much aware of when the President is a liability. Under those conditions, they have an understandable desire to keep him at arm’s length, as we have seen in “purple” state Senate races in Colorado, Iowa and New Hampshire this fall.

In their forecast models, political scientists try to account for both the surge-and-decline and the referendum factors by including a midterm variable, but also a measure of the president’s approval ratings. However, we do not want to overstate the degree to which the midterm is all about the President. As this table from Pew shows, even during the current election cycle, only about 32% of voters see their midterm vote as driven by opposition to Obama, while 20% say it is a vote in favor of Obama. That means 45% of those surveyed say their midterm vote has nothing to do with the President! And, as the chart indicates – that’s not unusual; many people in past midterms say their vote is not a referendum on the president’s performance.

http://www.people-press.org/files/2014/10/10-23-2014_04.png

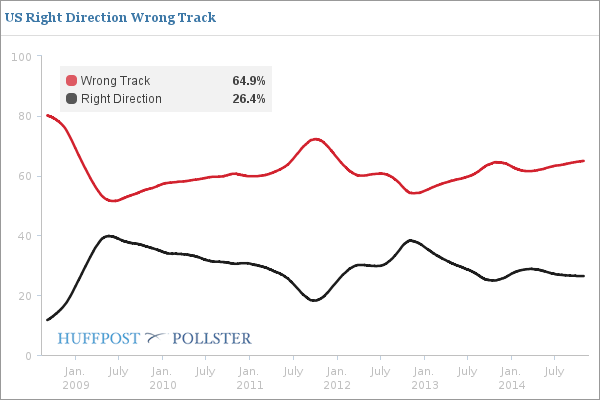

So, if not just the president – what is the midterm about? One factor is a general assessment of how well the country is “doing”, captured in questions asking whether the country is on the right track or not. Here we see that most people think the country is currently on the wrong track.

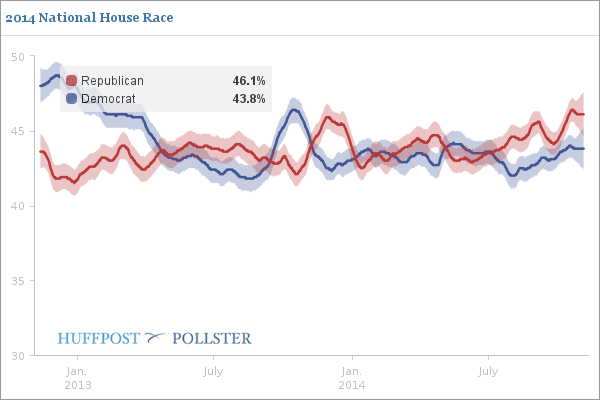

Another influence is the relative preference for one party or the other, often measured in the generic ballot question.

On this measure Republicans also have a slight advantage. Finally, the economy does matter, even in midterm elections, and some measure of economic conditions is often included in fundamentals-based forecast models. For example, Michael Lewis-Beck and Charles Tien include a measure for changes in disposable income in their forecast model.

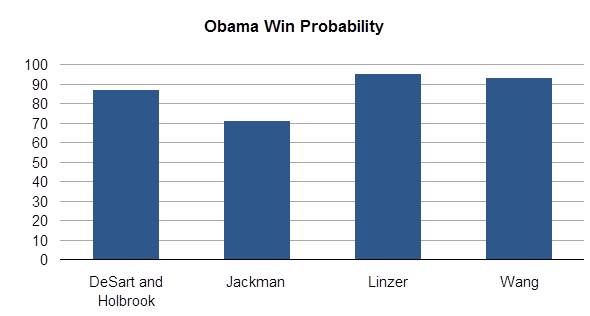

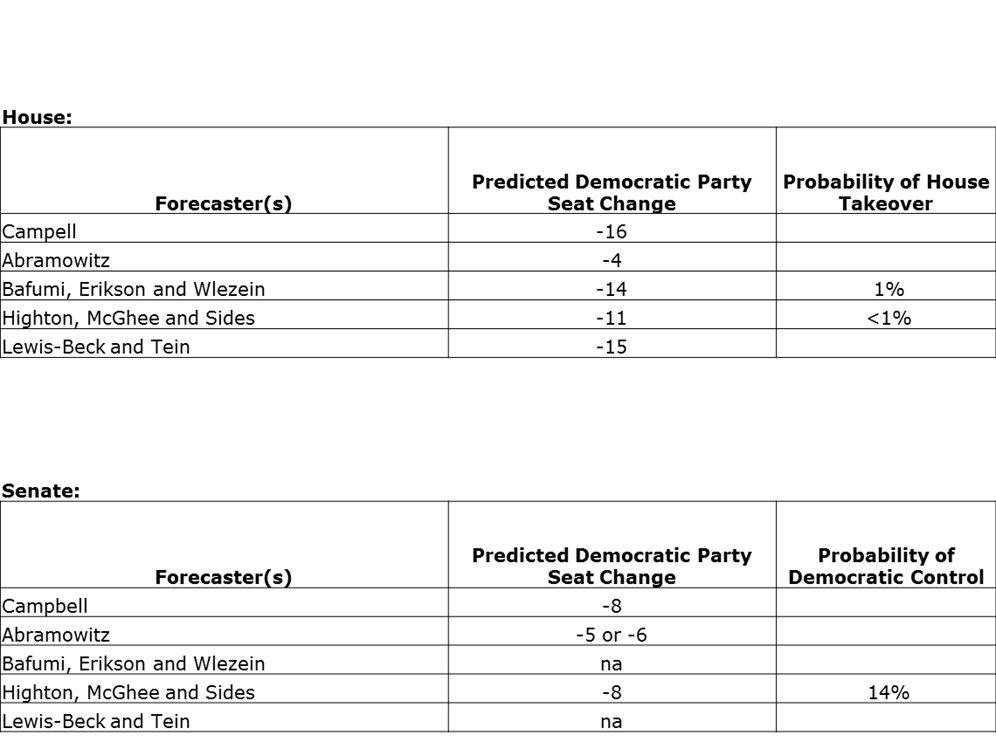

When we incorporate all these variables into a “fundamentals”-based forecast for today’s midterm elections, what do we get? Middlebury student Day Robins put together this chart summarizing the predictions made by several political science forecast models. (Note that some models only forecast House results, some only Senate, and some do both. Note also that most forecasts do not estimate a probability of a party taking over a chamber.)

Note that these models are not driven by the same logic that drive predictions based on poll aggregation, such as those by Drew Linzer at the Daily Kos or Mark Blumenthal’s Huffington Post. Poll-driven models are likely to be very accurate – maybe more accurate than fundamentals-only polls – but they don’t tell us why the polls turn out the way they do. For that, we need to turn to political scientists. And, as Robins’ chart makes clear, the fundamentals – the fact that this is a midterm, the President is unpopular, Democrats have more exposed seats, the economy is sluggish and generally more people think the country is on the wrong track – does not bode well for Democrats in either the House or the Senate. How badly will they do? On average, the models indicate Democrats will lose 12 House seats, with the median figure 14. In the Senate, the models say Democrats will lose on average 7 seats, dropping them to 48, with the median at 8 seats. Both forecasts sound right to me. To make it official, I’ll go with a Republican pickup of 8 Senate seats and 14 House seats. That will give you all something to root against tonight!

No turnout machine, no matter how sophisticated, can make much of a dent when the fundamentals mean you are moving electorally against a strong partisan headwind.

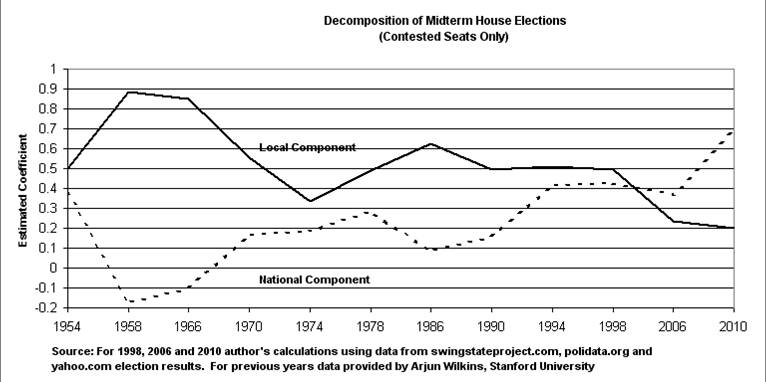

Keep in mind that, as the table above shows, as midterms elections have become increasingly nationalized, the partisan tides affect all candidates to a much greater degree. And so I expect it to go today. This is likely to be a predominantly nationalized election, one in which, taken collectively, the fundamentals favor Republicans more so than Democrats.

I’ll be live blogging from the “Karl Rove” Crossroads Grille tonight, while simultaneously trying to keep the Middlebury students from crying in their beer. I hope you can join in – it’s been a while since I’ve been able to do a live blog.

See you at 7:30 – by then they may have already called the Vermont races!