I’m working on about 3 hours sleep but wanted to give some initial thoughts regarding yesterday’s completely unexpected Senate and House results. At last check Republicans had picked up at least seven seats in the Senate, giving them a 52-43 margin (with two independents caucusing with Democrats.) However, with all the votes in, it appears that Republican challenger Dan Sullivan has ousted incumbent Democrat Mark Begich in Alaska, which would give Republicans 53 seats. Meanwhile, Virginia is headed to a state-mandated recount between incumbent Democrat Mark Warner and Republican challenger Ed Gillespie, and Louisiana will hold a runoff between Republican Bill Cassidy and incumbent Democrat Mary Landrieu in December. I suspect Cassidy will win the runoff, but there’s a good chance Warner survives the recount. So, conceivably Republicans could end up with 54 Senate seats which would be a net gain of nine.

In some ways the House results are equally impressive for the Republicans, given how few races were really up for grabs and the fact that Republicans went into yesterday already holding 234 seats. As of now it appears Republicans have netted 14 seats to push their majority to 243, but with results still pending in more than a dozen races that total could go up to as much as 19 seats gained. One has to go back to the 80th Congress (1947-49) to see a Republican House majority that big.

So, what are we to make of these results? To begin, it’s important to resist the inevitable tendency for pundits to overreach in their effort to discern “the message” the voters send yesterday. Already I am reading that the results indicate 1) a rejection of Obama, 2) a rejection of Democrats’ “war on women” 3) a rejection of Democratic liberal governance or maybe some combination of all of these. Some Democrats, not surprisingly, are suggesting that Republicans “bought” the elections due to backing from Superpacs.

The reality is that while this was a good night for Republicans, the results were driven by midterm election dynamics that political scientists have long documented. In this respect last night’s results were not unusual – nor were they even unexpected, at least based on fundamentals-driven forecasts. The most important point to remember is that the electorate in a midterm is different than what we see in a presidential election year, a point I made repeatedly last night. I haven’t seen turnout figures, but I’m guessing turnout was about 40%, down about 18% from 2012’s presidential election. More important than the size of the turnout, however, is its composition: yesterday it skewed older, whiter and more affluent than the electorate of 2012, and these are all attributes associated with a greater propensity to vote Republican.

More generally, the President’s party almost always loses House and Senate seats in a midterm – this is as close to a covering law that we have in political science. The magnitude of last night’s House losses by Democrats were surely attenuated somewhat by the fact that Republicans controlled so many seats, but nonetheless a net gain of 14-19 House seats by Republicans is well within the norm for a midterm election. On average, the president’s party loses about 28 seats in these midterms during the post-World War II era.

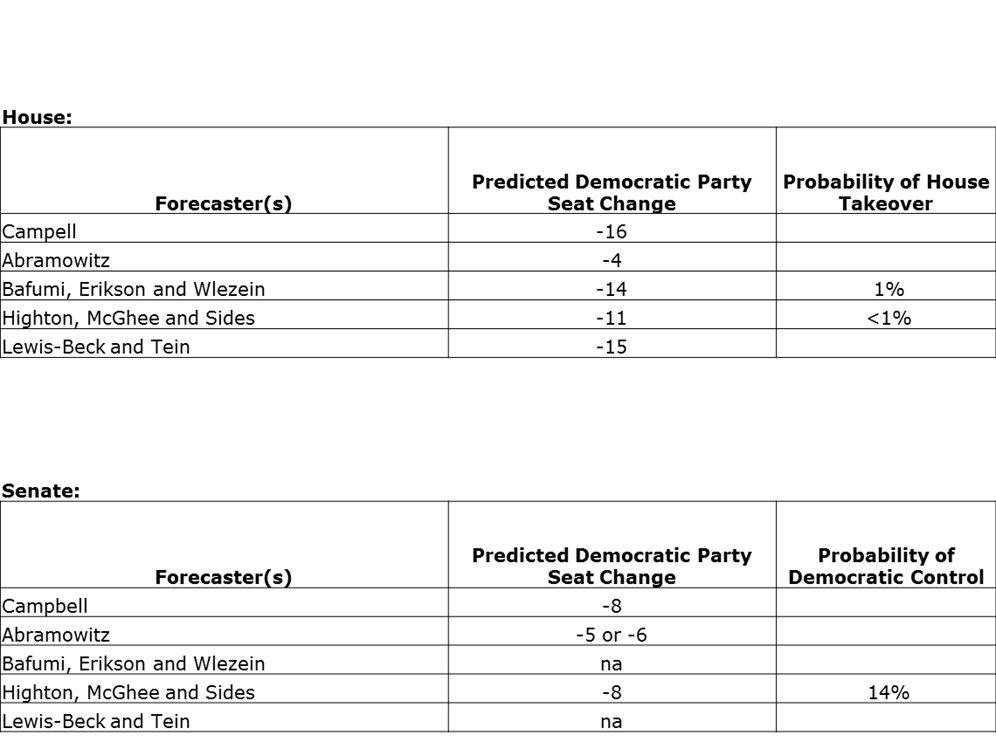

In the Senate Republicans did better, but not unusually so based on the fundamentals. As this chart indicates, political scientists who forecast the Senate race thought Republicans would pick up 8 seats based on the state of the economy, Obama’s approval ratings, and the prevailing view among most voters that America was headed on the wrong track.

Yes, this election was in part a referendum on Obama, but exits polls indicate that fully 45% of voters didn’t factor Obama’s performance into their vote at all, while 19% said their vote was meant to express support for him, so this can’t be viewed as a wholesale rejection of his presidency. More generally, when the economy is weak, the president suffers from low approval ratings and people are generally dissatisfied with the state of the nation, we should not be surprised that a Republican-oriented electorate dumped on members of a Democratic president’s party in Congress. Indeed, the greater surprise would have been if Democrats somehow held onto their Senate majority in the face of these fundamentals.

Of course, elections have consequences, and yesterday is no exception. To me, the most important is that these results are not likely to reduce polarization in Congress. Consider the Senate Democrats who were turned out last night. David Pryor was the second most conservative Democrat in the Senate, Mary Landrieu (who may yet hang on) the third most, Kay Hagan fourth and Mark Begich 12th among the 55 Democratic/Independents Senators. It is almost certainly the case that the Republicans replacing them are not going to be more moderate, although I confess to not knowing enough about them to place them on an ideological scale with any great degree of confidence. Still, I’m fairly confident polarization is not likely to decrease during the next two years.

In looking ahead, my guess is that the Senate will become more unruly – not less so – during the next two years. This is partly because the Democratic caucus has shifted left with the loss of its more moderate members. But it is also because several conservative Senate Republicans – with at least one eye on a potential 2016 presidential run – will view this election as an opportunity to push conservative policies designed to appeal to the party base. As David Mayhew reminds, for legislators the payoff is more often in the position taken than in the legislative results. Similarly, I see no reason why Obama is going change his ideological leanings as a result of last night’s “shellacking” redux. Presidents – like any politician – are not infinitely malleable when it comes to ideology. They have core beliefs that guide their conduct, although in Obama’s case those beliefs sometimes appear frustratingly opaque. Rather than do a governing about face, Obama is likely going to accommodate Republicans when he can, but otherwise wield that veto threat to block Republican initiatives, just as Gerald Ford, the two Bushes and Bill Clinton did when they faced an opposition-controlled Congress. We may see legislation passed, but only where both parties see it in their own interest. In short, last night’s election is not likely to have affected the strategic calculus that has governed relations between Obama and Republicans to this date.

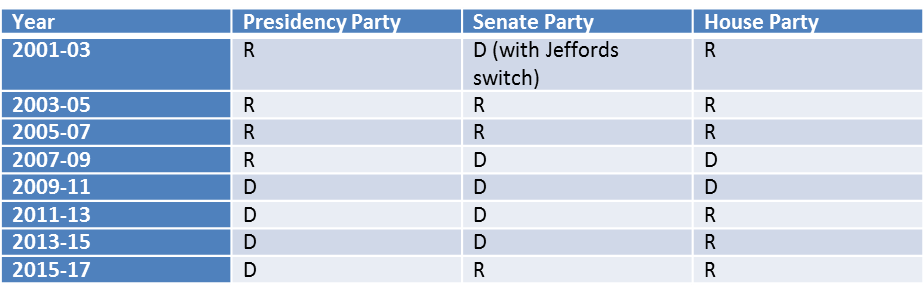

A final thought. As the table below indicates, we have cycled through almost every possible configuration of partisan control of our national governing institutions – a period of instability that testifies to the public’s apparent unwillingness to give governing power to one party or the other for any significant amount of time.

As long as individual Senators and Representatives believe that their electoral fortunes rest in part on the popularity of their party’s “brand name” among voters, and as long as the parties’ governing coalitions appear evenly matched even as they grow increasingly polarized in views, it remains the case that each side will usually conclude that it is not in their interest to compromise. And so we appeared destined to cycle through still another governing configuration.

As long as individual Senators and Representatives believe that their electoral fortunes rest in part on the popularity of their party’s “brand name” among voters, and as long as the parties’ governing coalitions appear evenly matched even as they grow increasingly polarized in views, it remains the case that each side will usually conclude that it is not in their interest to compromise. And so we appeared destined to cycle through still another governing configuration.

Next up: the 2016 elections. Let the campaigns begin!

How confident are you that the 45% of exit poll respondents who claimed that Obama’s performance didn’t factor into their vote actually mean that? I would imagine that if pollsters pressed people on this, follow up answers would reveal a large assortment of reasons for voting, a large portion of which would be related to the president at least in part. People may be unwilling to call their vote a referendum or not realize it themselves, but it seems unlikely that 45% of people fully ignored the presidency on election day.

What other options were available to respondents? I couldn’t find anything in the exit poll link on this question.

Jesse – You are right, of course – exit polls are an imprecise measure of voter motivations, in part because voters are often asked to choose one answer from a set menu of responses, when in fact they may wish to choose several responses. As you suggest, behaviors, such as voting, are often motivated by multiple reasons. It is also the case that exit polls are not always representative of the voting population in any single election. Still, I’m willing to accept that for many voters, Obama was not the primary determinant of their choice in this midterm, even if he was lurking somewhere in the background.