Charlie Cook, the venerable elections and polling guru whose Cook Report is a must read for political junkies, posted an interesting article today headlined “It Shouldn’t Be Close.” In it, Cook argues that based on the economic “fundamentals” alone, Romney should be leading Obama in the polls. He writes, “Whether one looks at polling measurements of whether voters think the country is headed in the right direction, at consumer confidence, or at key economic measurements such as growth in gross domestic product, deviations in the unemployment rate, or the change in real personal disposable income, it is puzzling, to say the least, why polls show President Obama and Mitt Romney running neck and neck. Incumbents generally don’t get reelected with numbers like we are seeing today.”

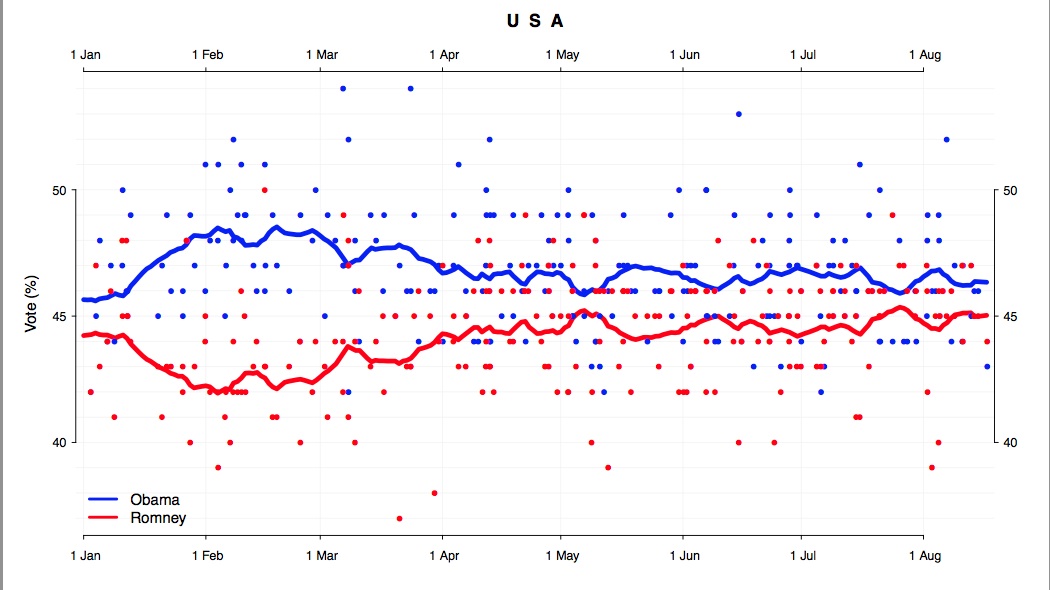

If the economic fundamentals are as lousy as Cook suggests, why do the national polls suggest that not only is Obama still in the race, he is probably slightly ahead? Cook believes it is because of the campaign missteps Romney has made, such as allowing Obama to frame the media narrative in terms of Romney’s tax returns and Bain experience, combined with Romney’s lackluster personality. Cook’s explanation, focusing as it does on issues of campaign tactics and personalities, would likely meet with approval by most pundits. As longtime readers won’t be surprised to hear, however, I think Cook is wrong to dismiss the economic fundamentals. In fact, those fundamentals – at least some of them – do not necessarily suggest that this race “should not be close.” As I noted in an earlier post, based on second quarter GDP growth numbers alone, history suggests Obama will win a smidgen more than 50% of the two-party popular vote. True, this doesn’t indicate a landslide victory for Obama, but neither does it suggest Romney should be winning this race, despite Cook’s assertion to the contrary. Of course, 2nd quarter GDP growth alone doesn’t explain everything about an election outcome. But if even you include other factors, such as Obama’s current approval rating and the fact that he’s an incumbent, history still gives Obama a slight advantage in the popular vote, as indicated by forecast models by Alan Abramowitz and John Sides and Lynn Vavreck.

Of course, as Sides reminds us, these forecasts are based on probability models that include a fair share of uncertainty, so while the economic fundamentals suggest Obama should win, it doesn’t mean he will. (This gives me a chance to plug John and Lynn’s new book on the 2012 election, which I am certainly going to assign in my elections course.) I want to go a step further than John, however, and suggest that we should not dismiss Cook’s analysis in its entirety. For, in truth, not all forecast models based on economic fundamentals indicate that Obama should win this election. For example, Jim Campbell points out that if we expand the timespan of forecasters’ analyses to include average GDP growth from a president’s second year through the second quarter of an election year, Obama’s reelection chances look a bit less promising.

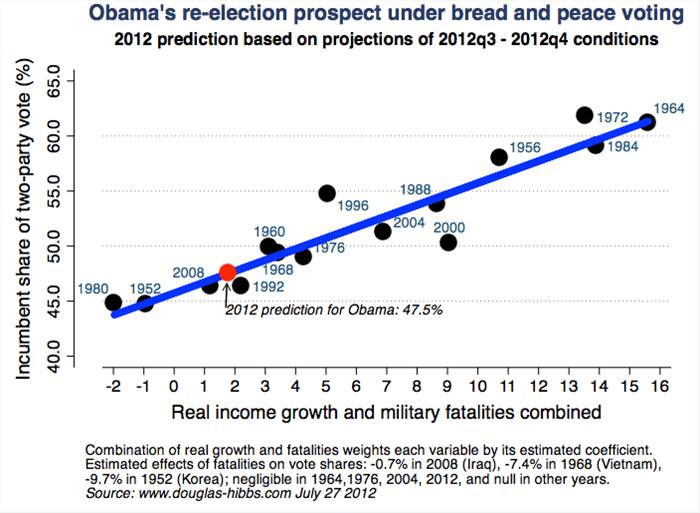

Moreover, as I discussed in this post, Doug Hibbs’ “Bread and Peace” model, which has proved reliable in the past, predicts that Obama will receive just 47.5% of the two-party vote come November. Rather than GDP, Hibbs’ model includes measures for changes in disposal income and American military fatalities. It is a reminder that there is more than one way to gauge economic fundamentals.

To further complicate matters, according to a recent press release, two Colorado University professors are poised to release their own study purportedly showing that based on state-level economics factors, Romney is going to win 52.9% of the two-party vote, compared to Obama’s 47.1%. I’ve not yet seen the model on which this forecast is based so I’m not ready to evaluate their prediction, but it potentially provides further evidence that Cook is not entirely off base in arguing that Romney should be doing better in the polls.

My point is that even political scientists are not in full agreement regarding what aspects of the economy are most “fundamental” to presidential election outcomes. Moreover, each of their forecasts comes with a degree of uncertainty built into their estimates. This means that, in a close election, forecast models that differ in their prediction regarding the election winner in November could nonetheless all be considered accurate if the final popular vote falls within their specified level of uncertainty. Of course, this is small consolation to the layperson who wants to know now who the likely winner will be come November 6th, which is what most of you care about! But it is important to remember that political scientists speak in probabilities, based on past events, not certainties.

So, where does the election stand today? I would make two points. First, the median prediction of the econometric forecast models of which I am aware right now hovers just above the 50% mark, suggesting that Obama is a very – emphasis on very – slight favorite. Second, models that include measures of Obama’s approval ratings and/or current national or state-level polling are usually (but not always) slightly more bullish on Obama’s prospects than are models like Hibbs’ that are based solely on the fundamentals. That suggests to me that that the key question looking ahead is whether opinion polling and Obama’s approval ratings begin to change in ways that indicate that voters, as they pay more attention to the election, will adjust their views closer to what some forecasters like Hibbs believe the economic fundamentals dictate. Keep in mind, however, that based on economic fundamentals alone, it is not necessarily the case that Romney should be winning this election. That assessment depends, in part, on what fundamentals one includes, and across what time span. And, as my stockbroker I. B. Guessing always reminds me, past performance is no guarantee of future results.

(Note that many political science forecasters will be unveiling their latest predictions at the 2012 APSA conference which meets in New Orleans next week. When those papers are available, I’ll try to update this post.)

Update 3:24 p.m. Nate Cohn has an initial and somewhat skeptical reaction to the Colorado forecast I allude to above but again, I haven’t actually seen the specifics yet of their model so I’ll withhold comment for now. Note that I mistyped their prediction of the two-party vote in my initial post – that’s been corrected.