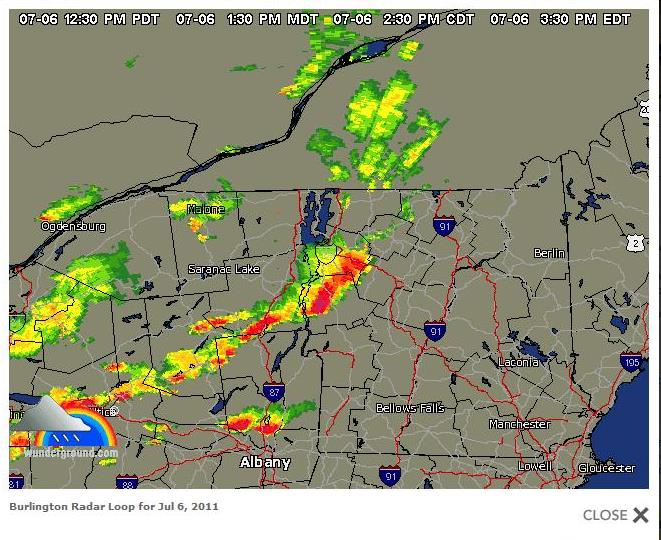

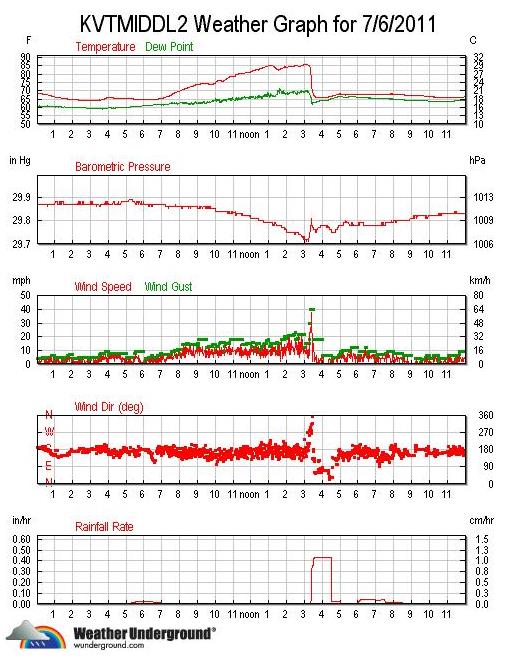

Anyone around this summer, or past readers of this blog, will remember a large thunderstorm that ripped through Middlebury two days after Independence Day. Several trees were struck by lightning, which I wrote about after the storm.

The largest tree struck was the Norway spruce in the Main Quad, one of the ones remaining after we removed part of the line. I wrote this summer how the tree was struck at the top, and exhibited a spiral shaped scar all the way down the trunk, exiting at the root flare. We didn’t know if the tree was going to make it or not, but had hopes.

It’s not the voltage that kills trees, but the water. Over 100 million volts strikes the tree, but it is the water heating quickly turning to explosive steam that causes failures. (Another blog post, on a lightning stuck Ginkgo, has much more detail) Damage in trees can be tricky, often with the worst of the damage unseen.

There was damage seen immediately. Long strips of bark went flying across the quad, and a scar opened up, spiral shaped, following the grain of the wood down the trunk. The high sap content of spruce makes it susceptible to such long scars.

I’d been worried about this tree all summer, and was watching it closely. All the limbs near the scar started to die, and the color of the remaining ones seemed a little off, but still green.

I’d been worried about this tree all summer, and was watching it closely. All the limbs near the scar started to die, and the color of the remaining ones seemed a little off, but still green.

During a closer hazard evaluation this summer I discovered two things, one bad, the other worse. The first was the size of the scar, and while this shouldn’t have surprised me, it did.

During a closer hazard evaluation this summer I discovered two things, one bad, the other worse. The first was the size of the scar, and while this shouldn’t have surprised me, it did.

The scar that formed in the summer seemed minimal. While very long, it only seemed an inch or so wide.

The bark hid quite a bit of damage, and another small crack that wasn’t even open this summer showed another major wound. Peeling away at the wound showed extensive damage, much larger than we’d first thought. Overall, it seems about 1/3 of the sapwood (the live wood beneath the bark that conducts water and nutrients) around the trunk has died, severely compromising the tree.

I’ve seen trees limp along with scars like this for many years, most often in a forest setting. Trees in communities are connected in several ways, relying on each other for support and nutrients. They also tend to be the best trees for the site, adapted to soil and weather conditions. Trees in an urban or landscape setting are under more stress, either from a singular status in the landscape, more exposed to wind by themselves, or stress from poor soil conditions its genetics just can’t handle gracefully.

I’ve seen trees limp along with scars like this for many years, most often in a forest setting. Trees in communities are connected in several ways, relying on each other for support and nutrients. They also tend to be the best trees for the site, adapted to soil and weather conditions. Trees in an urban or landscape setting are under more stress, either from a singular status in the landscape, more exposed to wind by themselves, or stress from poor soil conditions its genetics just can’t handle gracefully.

This fall was a good one for fungus, with cool moist conditions. The base of this spruce showed a colony of fungi following along one of the major roots of the tree. Later that same month the same fungus appeared following a different root. This indicates a root rot, a type of fungus eating away at the roots of the tree.

I’ve spoken with an arborist friend of mine who suggests immediate removal. He’s seen similar cases, where trees exhibiting root rot like this suffer from wind throw, heaving over in a storm. The clay soils of our quad make this species very susceptible to this, spruce not being a deep rooted tree to begin with, in clay soils even more so.

I’ve spoken with an arborist friend of mine who suggests immediate removal. He’s seen similar cases, where trees exhibiting root rot like this suffer from wind throw, heaving over in a storm. The clay soils of our quad make this species very susceptible to this, spruce not being a deep rooted tree to begin with, in clay soils even more so.

While I like this tree quite a bit, the chance this tree could suffer a catastophic failure in such a busy location on campus is too much of a chance to take. The remaining tree, the large Norway spruce with the interesting trunk, will remain.

You must be logged in to post a comment.