… you have identified the geographic features that your map should show [SIMPLIFY THE WORLD] to help your audience [MAPS ARE FOR PEOPLE] answer or generate questions [DONE NOT DUE]. You’ve identified the hierarchy of importance that your map will express visually [VISUAL HIERARCHY]. And now you will need to show labels on your map for the names of some things…

We don’t just read text. We also see it. We take the appearance of text to be meaningful. When the appearance is haphazard or all the same, then it will be more difficult to read the map.

Let’s look at John Bartholomew’s 1856 map of New York, Vermont, New Hampshire and Rhode Island. Your first impression might be: wow, he sure put a lot of labels on that map! As Erwin Raisz (1962, 51) explained:

“There was a time, not too long ago, when a map publisher’s chief claim to superiority was that he could press more names into his maps than his competitors. Nowadays we recognize that a map should be more than a multitude of place names, and we omit all names not necessary for the purpose of the map.”

While we may no longer need or want to press so many letters onto a map today, we might still appreciate Bartholomew’s skill at crowding so much text on a page and still making the text quite legible. He’s made the map in a way that helps us read the names of places and also to help us compare and contrast different kinds of geographic things. For example, our eyes can move from one county to another and ignore everything else. Or we can look at a village and then scan quickly for the nearest larger town.

Study the map and you should be able to see a taxonomy of geographic things conveyed through the style, form, size, contrast, and positioning of the letters:

Small villages: lower-case, italic, aligned parallel with latitude.

Larger towns: lower-case, not italic, same alignment

Cities: all caps, bold, same alignment

Counties: larger type, all caps, bold, aligned in ways that arc across county regions.

States: larger still, all caps, bold but hollow, spreading across state regions.

Rivers: lower-case, italic, aligned with rivers.

And so on. The visual system of the lettering helps the map reader distinguish different classes of things (villages, towns, cities, etc) and their ordinal relationships, particularly their relative size (villages are smaller than towns which are smaller than cities).

The key idea here is that text on maps convey meaning with two different sign systems (Robinson et al, 1984, 195; Krygier and Wood, 2005, 233). In one system, a verbal system, the symbols represent the names of things by encoding sounds (when you read these words do you “hear” sounds in your head?). In another system, a pictorial system, the symbols represent nominal classes and ordinal characteristics of things by encoding images. This means text on maps function as little multimedia messages. Words and pictures work together to communicate. It’s just that with text on maps, the words and pictures are often built from the same material (letters).

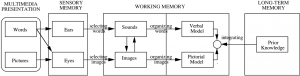

Extensive research by Richer Mayer and colleagues (2009, 60-76) indicates that learning from multimedia presentations involves at least three things. First, people seem to possess two separate channels for processing visual and auditory information. Second, we have a limited capacity to process information in each channel at one time. Third, we are actively engaged in learning by attending to incoming information, creating coherent mental representations, and integrating mental representations with other knowledge.

The flowchart above shows Mayer’s (2009, 70-79) model of multimedia learning (click on it to see it better). In map presentations, we use our eyes to actively engage with the information and select groups of letters from the map that we hold in our working memory as images. At this point, the processing system splits into two channels. As pictorial information, we organize the images into coherent representations by forming relationships and building a pictorial mental model. As verbal information, we first make mental sounds from the images of the letters and then organize these into coherent verbal models. The final step involves integrating these pictorial and verbal models with knowledge from long-term memory and possibly with each other.

Mayer’s model of multimedia learning indicates that when people “read” letters on a map, they process both verbal and pictorial channels in their working memory, which has a limited capacity. Good mapmaking usually involves developing a pictorial system for text that helps people actively engage with the text without adding unnecessary load to working memory.

Bortholomew’s map does this in several ways. The map conveys commonsense categories — villages, town, cities, counties, states, river, bays, etc — that people will probably already know, which helps the reader integrate the information with the mental models they already hold in long-term memory. (The map will be harder to read for someone who doesn’t know what a “county” means). The map is also visually consistent when representing each type of thing which lets our eyes quickly scan the text before we select information to read. The map also shows us relationships that help organize the information (the type for towns appears bigger and more durable than villages).

Mayer’s model of multimedia learning may also help mapmakers understand limits to the the visual representation of geographic taxonomies. Robinson et al (1984, 198) noted:

Cartography conventionally uses different styles of lettering for different nominal classes of features, but this may be easily overdone. Although there is little evidence, there does seem to be some indication that the average map reader is not nearly so discriminating in reactions to type differences as cartographers have hitherto thought. The use of many subtle distinctions in type form for fine classificational distinctions is probably a waste of effort.

From Mayer’s model, we can expect at least three limits to the representation of geographic taxonomies through type style: (1) when the differences in text style are not sufficient to help the reader select information, (2) when the text styles do not help the reader organize the information into verbal or pictorial models, and (3) when the classes or ordinal relationships of things are not common-sense or pertinent to the questions that the map is intended to help the reader understand.

Make a list of the kinds of things that will appear on your map. Use commonsense categories. Choose type styles to associate similar kinds of things, distinguish different kinds of things, and convey ordinal relationships between things. Use hue, size, capitalization, bold/italic, fonts and placement to develop your taxonomy.

Develop coherence between your text styles and the geometric symbols (points, lines, polygons) that they label [VISUAL ASSOCIATION]. Think about how to make your typeface intuitive and/or realistic [SYMBOL RESEMBLES REFERENT]. Make your labels legible through strong contrast [BETWEEN BUT NOT TOUCHING.]

Home > About This Post

This was posted by Jeff Howarth on Thursday, January 15th, 2015 at 8:43 pm. Bookmark the permalink.

Subscribe to the RSS feed for all comments on this post.

Filed Under

Tagged

Hosted by sites.middlebury.edu RSS: Posts & Comments