Read it on Archive-It’s blog or below!

Unauthorized Voices in the Archive: Documenting Student Life in Middlebury College’s Community Web Archive

The following is a guest post by Patrick Wallace, Digital Projects & Archives Librarian at Middlebury College.

In November 2015, as I stepped into my position as Middlebury College’s first digital archivist, our Director of Special Collections approached me for ideas on how to begin work toward three mutual goals: providing boldly promiscuous, public access to our digital collections; preserving born-digital and web content; and, including fuller representations of student life in the college archives. Like many institutions, Middlebury’s previous efforts to preserve institutional memory emphasized – at least implicitly – the authorized, public face of the college: official publications, administrative business, sanctioned student activities, and so on. The college archives therefore represented a mostly sanitized view of campus culture, a clean and uncontroversial history that we in Special Collections found unacceptable at a time when student protests over issues of discrimination, violence, gender and sexual identity, racial diversity, and a host of critical social justice issues were shaking up campuses nationwide, and as Middlebury was making conscious institutional efforts to improve on-campus diversity, inclusivity, and community wellness. Subsequently, our first major initiative toward change was the Middlebury College Community Web Archive, which began, and remains, a central effort by the college archives toward constructing a more just institutional memory.

Queer Faces of Middlebury, a student-created photographic narrative documenting diversity among students, staff, and faculty.

A major goal of the project has been to capture and preserve discussions happening in Middlebury’s culturally diverse activist margins. Student debate and activism happens in large part online, especially via Facebook, Twitter, WordPress, Tumblr, and other social media outlets. Students often speak more freely in these virtual spaces than they might, for example, in the editorial pages of the college’s newspaper or in an institutionally-sanctioned town hall discussion. As a long time fan, I had been suggesting that the Internet Archive would play a central role in our digital collections strategy from the time of my job interview, and the ideas behind the Community Web Archive delivered a perfect justification for partnering with Archive-It.

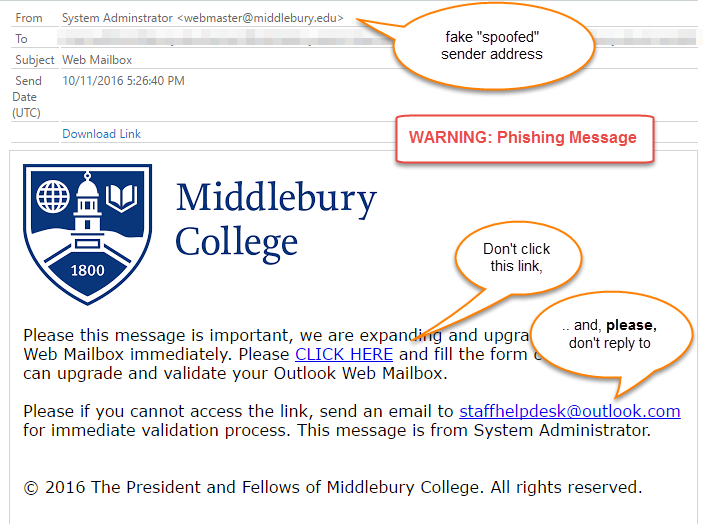

Identifying and collecting student-created content from unsanctioned online sources (e.g. sites outside of our institutional web domain, or social media feeds from organizations unaffiliated with the college) was a clear priority, but not without a host of risks and difficult choices: we had concerns about unfairly appropriating student voices for our own work; we wrung our hands over how to organize potentially controversial materials; we discussed concerns about administrative pushback; we worried about inspiring resentment or mistrust in students who were critical of the establishment to which we in the archives are certainly beholden. As archivists and curators, we have immense power to shape history. It is my decided opinion that participating in the soft censorship of omission in deference to a personal fear of backlash is grossly unethical. Therefore, the famous words of computing pioneer Grace Hopper–“it is easier to ask for forgiveness than to get permission”–have been a central guiding principle of our digital collections strategy.

Image from a student created “disorientation guide” questioning institutional efforts at improving campus diversity (disorientmidd.wordpress.com).

Yet, the archives are also an institutional authority, and when our artifacts represent voices set in opposition to that same authority, it is imperative that we remain sensitive to the risk of exploiting or misrepresenting student experiences in our collections. Organization and definition presented an immediate challenge. YouTube channels by Middlebury’s acapella singing groups could certainly live comfortably and uncontroversially alongside the Mountain Club’s Facebook account. But what about a pseudonymous student’s blog post about the failed and traumatic institutional response to their sexual assault? What about an environmentalist polemic that cast Middlebury – the first school in the country to offer an undergraduate degree in environmental studies – and its administration in a less than favorable light? What about the website of a satirical publication that, while venerable on campus, is run independently of the college?

To answer the question of classification, I proposed that we turn to our original goal – to provide a full and honest view of student life – and make the choice not to impose artificial distinctions. Theater and mountaineering have long been a part of the “college experience” at Middlebury, but so have sexual violence and racial discrimination; to suggest otherwise would be fundamentally disingenuous and contrary to our aims. We reached out informally to a number of students and recent graduates, and encouraged them to speak with their peers in turn; all agreed that a boldly inclusive collection was the best solution. To be honest, I still do not know if this is a representative view among the student body, much less among the administration. However, I firmly believe that the Middlebury College Community Web Archive is the most radical, candid, and diverse sampling of student voices ever collected by the college archives.

Documenting broccoli served in a Middlebury College dining hall (proc-broc.tumblr.com).

Another key question was how to identify URLs for preservation, and do so in a way that allowed student participation in the curatorial process. An initial set of seeds was proposed by our Special Collections’ postgraduate fellow, Mikaela Taylor, a recent graduate who was aware of popular student publications and activities that might escape the attention of other library staff. However, we did not want all of the curatorial decision making to come from within the archives. We set up a Drupal form for URL submission linked from the library website, and Mikaela led promotional efforts encouraging students to submit their favorite websites, blogs, and social media feeds. The form is designed to be simple; aside from the site URL and a field for descriptive information, the form asks simply if the submitter has rights to the site content, and if not, whether or not they know who does. As a rule, if a URL is submitted by a Middlebury community member, it is included in the archive; we have chosen not to crawl perhaps half a dozen because their size or document count was more than our Archive-It subscription can currently accommodate.

One of our notable promotion campaigns came at the end of the spring semester, when graduating seniors traditionally post “crush lists” – creative posters listing platonic or romantic crushes from their college years – in common areas. A mock crush list created by Special Collections listed some of our favorite sites included in the web archive, with links to the submission form. The response was good, and provided URLs for several sites now in the collection. When facilities management began taking down the crush lists, students began posting scans and photographs to Tumblr; the site URL was submitted to the archives and added as a seed. Out of over a hundred seeds being crawled, only the crush lists site has been kept out of the public archive, because of concerns over privacy.

Middlebury’s URL submission form for students & faculty.

Work on the archive continues, and we are adding more seeds while actively developing workflows to bring WARC files from Archive-It into our nascent institutional repository. As I write this, the Middlebury College Community Web Archive contains 138 seeds (97 public) totalling over 53GB of data and a million documents, with an incredibly broad range of content: a collection of animated GIFs lampooning the college experience at Middlebury; local news articles about racist attacks carried out against a student government candidate via YikYak; blogs by students studying abroad that focus on cheese and textiles in different countries; Facebook pages representing Middlebury’s Black Student Union, LGBTQ+ activist groups, local musical acts, theater troupes, and fossil fuel divestment initiatives. Adding descriptive metadata remains a work in progress, but more than half of the public seeds include fairly rich descriptive information.

Submissions keep coming in and our promotional efforts have not abated. We are proud of the work our partnership with Archive-it has facilitated, and certainly hope our collections provide future researchers, students, and alumni with as much fascination and insight as we in Middlebury College’s Special Collections and Archives have gained through their development.

You must be logged in to post a comment.