This month, we offer book reviews by three guests writers. The first is by Joanne A. Schneider, currently a board member for Dawn Mountain (a Tibetan Buddhist center in Houston, Texas) and a retired librarian who worked at Middlebury for over 20 years as reference librarian and assistant college librarian before leaving to become library director at Saint Michael’s College and, later, Colgate University. Our second reviewer is Milo Stanley, Middlebury class of 2017.5, and a geology major from Maine. The third is by Literatures & Cultures Librarian Katrina Spencer.

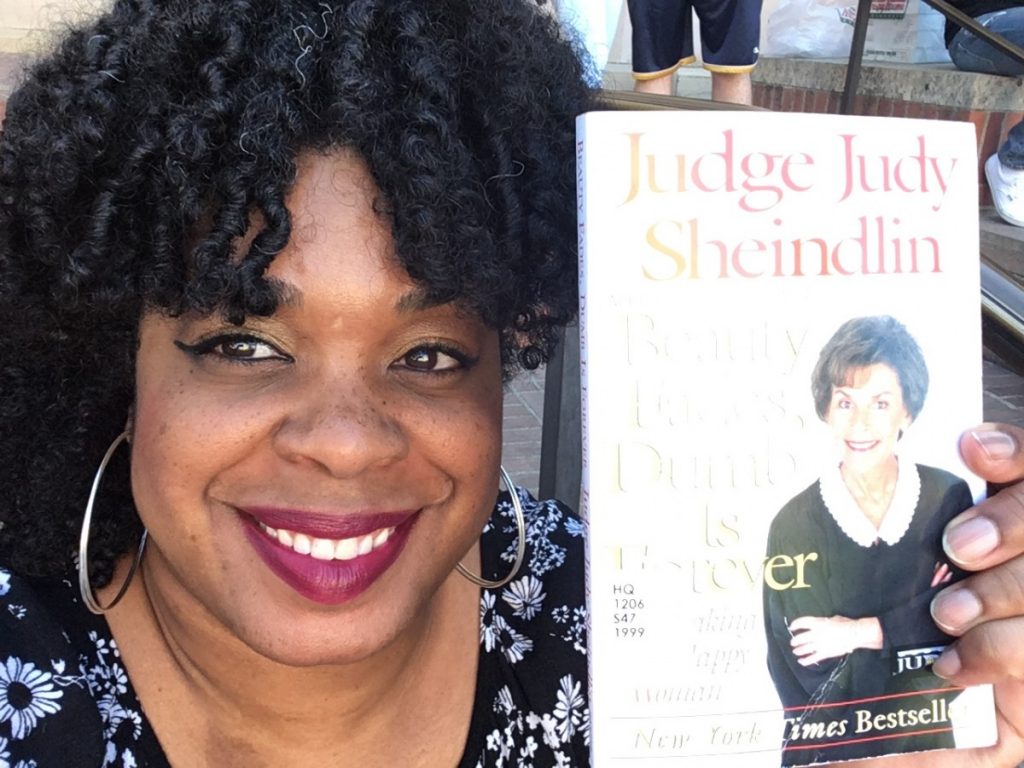

Jim B. Tucker, M.D. Life Before Life: Children’s Memories of Previous Lives, reviewed by Joanne A. Schneider

As a long-time Tibetan Buddhist, I belong to an online reincarnation book club run by Dawn Mountain. We just read Life Before Life by Jim B. Tucker, a child psychiatrist and medical director of the Child & Family Psychiatry Clinic, University of Virginia. This is the first of two books featuring American children.

Using a scientific approach devoid of religiosity, Tucker provides evidence for a selection of cases documenting children who describe memories of previous lives from more than 2,500 instances registered in the files of the Division of Perceptual Studies, University of Virginia. The evidence includes predictions based on dreams by previous individuals, birthmarks and birth defects that match usually fatal wounds on the bodies of previous personalities, and children’s past life statements.

Investigations record and verify statements, conduct controlled recognition tests, and document evidence to eliminate other explanations such as fraud, fantasy, overheard information, faulty memory, genetic memory, paranormal explanations, ESP, and possession. Reincarnation remains as the sole possibility. Information is provided about memories of past-life behaviors that impact the children’s current lives including phobias; other preferences, like gender identity disorder; and recognition of something or someone from the previous life. These suggest that behaviors and emotions, as well as memories, can carry over from one life to another, particularly when death has been sudden or violent.

The book ends by summarizing current scientific theories about the dualistic nature of consciousness separate from the brain.

In recounting these compelling stories “out of the mouths of babes,” Tucker continues the work of his predecessor, Ian Stevenson, M.D., who, as chairman of the UVA Department of Psychiatry, began to focus on this topic in 1958, primarily featuring cases of children in Asia. Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation, the first of Sevenson’s six books (all of which are available in the Davis Library collection) was originally published in 1966.

Reading this book takes me back to 1980, when I traveled to Montreal to see the Dalai Lama with my then spouse, Assistant Professor Don Lopez, Jr., whose purpose was to invite him to Middlebury on behalf of the Religion Department. As a reference librarian in the old Starr Library (now renovated and renamed the Axinn Center at Starr Library), I returned from the trip intent on insuring that the library would acquire Stevenson’s works and others related to Buddhist beliefs like reincarnation in preparation for the Dalai Lama’s first visit to Middlebury in 1984.

Thies Matzen’s Antarktische Wildnis: Südgeorgien, reviewed by Milo Stanley

Three days ago, I skied down the icy slopes of the Middlebury College Snow Bowl in a final farewell to the institution at which I’ve spent my past four years. Without getting into too many details, I’ll say that Middlebury and I have had a rocky relationship– the ways in which I chose to express my creativity here were generally viewed in an unfavorable light by the “Risk Management Team.” Anyone who has attempted to surreptitiously rebuild a motorcycle (aka “Fire Hazard”) in borrowed space can relate.

That being said, there are two entities on this campus that are truly worth their weight in scrap metal (and I’m talking about copper and its alloys, not aluminum breakage). The first of these are the green thirty-yard dumpsters behind the college recycling center. The list of items I’ve recovered from those beautiful yet tragic examples of American consumerism would take up several pages, though highlights include a piece of 2”x10” maple worth several hundred dollars, and Ron Liebowitz’s desk.

The other is the granite spaceship known as Davis Family Library. Davis has a lot to offer — nicely-tiled bathrooms, for instance — but also an amazing collection of books, a legion of friendly and helpful librarians, and a hidden treasure: Special Collections. Not long after I got to Middlebury, I discovered that I could actually ask for books that couldn’t be found in the stacks, or through interlibrary loan, and the library would purchase them. I set about systematically abusing this privilege, ordering obscure titles on the arcane topics in which I am interested, such as boatbuilding, blacksmithing, and woodstoves.

I am now remembering that I had originally set out to review a book in the library collection, and have wasted nearly my entire allotment of words not doing this. I have also just been informed that the library will close in 20 minutes, so here goes…

Antarktische Wildnis: Südgeorgien, by Thies Matzen, is perhaps my favorite of the twenty-six books I’ve ordered through the system described above. It’s in German, which I can’t read, but a paper insert in the back provides translation for the minimal text. Most of the pages are filled with stunning photographs of South Georgia Island, taken by the author and his wife during the year they spent living aboard a 30’ wooden sailboat in the waters surrounding this remote piece of land. South Georgia, Thies tells us, has the highest concentration of life in the word, due to upwelling ocean currents that enrich the lower tiers of the food chain. I’ve squandered many hours, and probably a few points of my GPA, poring over images of immense glaciers, forbidding peaks, endless flocks of seabirds, elephant seals, and two humans on their tiny floating home amidst it all. It’s healthy food for daydreaming, which, I believe, is one of the better qualities a book can have. Best of all, it’s in the library for years to come, so check it out and share the joy.

Judge Judy Sheindlin’s Beauty Fades, Dumb Is Forever: The Making of a Happy Woman, reviewed by Katrina Spencer

Having been on television for more than 20 years (!), it’s fair to say that Judge Judy is an American cultural icon. I was a teenager when I started watching her show and I still seek out the cases over which she presides on YouTube. If you haven’t seen the show, Judge Judy deals with many cases that have to do with broken households, personal loans of less than $5,000 and even car accidents. Her flavor of justice is swift and exacting and she has come to be known for her sharp wit.

This book, published in 1999, is a hybrid of memoir and self-help. Primarily written for women, it reminds them not to define themselves based on their marital status, to make their own rules of contentment, and to nurture their talents which will allow them to move about in the world with a sense of security, socioeconomic independence and confidence. I never thought I’d say it but Judge Judy is kind of my idol (of which I have rather few). I don’t agree with everything she says– in the book or on television. But I like the fact that she commands respect. I like her unabashed confidence. I like that she’s not easily intimidated. Can you imagine what the world would look like if all women were able to embrace themselves the way that she does? She is a feminist powerhouse.

While many of us are familiar with Judge Judy as a professional, this book gives readers a more intimate look at Judge Judy as a wife, mother, and household manager. She talks about what has worked in her two marriages and what hasn’t; how managing her familial and professional roles has not always been a piece of cake; and how some domestic chores need to be delegated for greater peace of mind. The tone is personal, comedic, and authentic, and the narrative is peppered with anecdotes involving her extended and nuclear families. I’d recommend this to most 20-year-old women who are still being told that their highest and most revered title in life will be “Mrs.” And I’d recommend it to 30-, 40-, 50-, and 60-year-old women who have believed that notion. It’s a quick and entertaining read that will keep readers engaged for a few hours.