I recently had the opportunity to tour the headquarters of Huawei, the largest technology company I had never heard of. Huawei is located in Shenzhen, China, a city of almost 12 million people that, 30 years ago, was a sleepy fishing village across the bay from Hong Kong. The tour took place first by bus since their campus sprawls over 500 acres. We then retired to their product demonstration showroom and learned about their impressive technology platforms: from tiny sensors that power the internet of things to cloud computing servers capable of processing millions of transactions per minute to wireless access points enabling sports fans to upload video directly from their seats in a stadium.

Most notable was an application that they had developed for video surveillance. On a wall-sized display, they showed a typical airport scene of people coming and going through the terminal. Layered on top of that display, a software program drew boxes around individual faces, and then created a database entry for each individual, performing facial recognition and recording the time and place. Then the demonstration pivoted; we chose an individual, and the software produced a map of every place that person had been picked up on camera over the last six months. Scary.

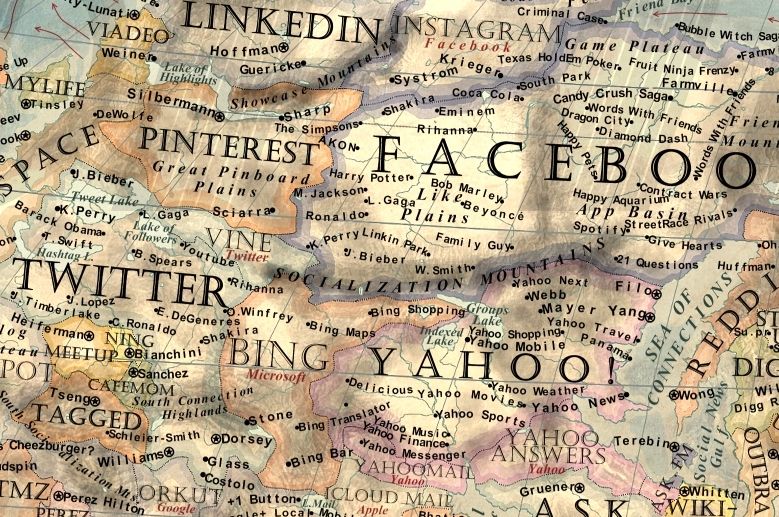

In reading the technology section of the New York Times just this week, there are stories about network neutrality, a Supreme Court case on the use of cellphone data in criminal investigations, the latest development in driverless cars and their implication for urban architecture, bitcoin’s continuing efforts to establish itself as a transnational currency, Facebook’s influence on the Italian elections, and the use of drones as a way to make air travel safer. The truly remarkable advances in technology over the last thirty years embodied by the showroom floor at Huawei, and the acceleration of these advances in the last decade, have profound implications for us individually as citizens, consumers, and workers, and collectively as a society, as evidenced by the headlines in the newspapers. What influence can we have over the directions these technologies take? How can we bend the curve of technology towards justice, social good, and addressing the world’s most pressing problems? And what does this have to do with a Middlebury education?

At Middlebury, our new strategic plan calls for us to move in the direction of cultivating digital fluency and critical engagement. As we consider the outsized role of technology in our current times, the time is right for us to engage directly in helping our students (and ourselves) learn to understand not only how modern technology functions, but also to learn how to think about the kind of world we want to create, and how technology can be used to help create that world. Increasingly we need to think about policy, law, economics, and our social contracts through the lense of technology, precisely to resist the technological determinism that at times seems inevitable when we abdicate responsibility for understanding how things work, and for thinking critically about how they might work differently.

For the library, this represents a great opportunity to re-imagine our long-standing commitment to information literacy instruction, and to reframe that work in a broader context. Our students still need help learning to formulate research questions, navigate the research process, understand the content and structure of the various systems they use to find information, contextualize primary sources, and develop a keen sense of what is (and isn’t) relevant and reliable information. In short, to become sophisticated researchers. But as I read the call for us to cultivate digital fluency and critical engagement, I see an opportunity to be more expansive in our efforts, and to help us all become better producers and consumers of information, to think about information as part of a broad cultural and economic system, and to be more actively engaged in shaping the future of our increasingly technologically-mediated world.

There is much work to be done. We need to come to agreement on what we mean when we say “digital fluency” and to find ways to connect this work both to the curriculum and to the rest of our students’ lives. We need to explore what this looks like not only within the undergraduate curriculum, but also with the curriculum at the Institute and the Schools. Given the rate of change and the growing influence of technology in our everyday lives, there is real urgency to engaging now with the hard but important questions in front of us.