![]() “As an unregulated river,” Franklin Roosevelt declared at the inauguration of California’s Boulder Dam in 1936, “the Colorado added little of value to the region this dam serves.”[footnote]Quoted in Andrew Needham, Power Lines: Phoenix and the Making of the Modern Southwest (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), p. 26.[/footnote] Roosevelt expressed a belief held by many people at that time (and still held by many today) that the need to maintain and expand our energy use outweighs the need to protect the natural environment.

“As an unregulated river,” Franklin Roosevelt declared at the inauguration of California’s Boulder Dam in 1936, “the Colorado added little of value to the region this dam serves.”[footnote]Quoted in Andrew Needham, Power Lines: Phoenix and the Making of the Modern Southwest (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), p. 26.[/footnote] Roosevelt expressed a belief held by many people at that time (and still held by many today) that the need to maintain and expand our energy use outweighs the need to protect the natural environment.

In 1960, Eliot Porter made a rafting trip down the Colorado River through Glen Canyon in southeastern Utah. Porter was amazed by the colors and shapes of the canyon, which, with the impending completion of the Glen Canyon Dam, was soon to be flooded. When the Executive Director of the Sierra Club, David Brower, saw Porter’s photographs of the canyon, he quickly decided to publish a book chronicling the soon-to-be lost landscape. When The Place No One Knew, Glen Canyon on the Colorado was published, Brower sent a copy to the president and every member of congress, along with a letter pleading for construction to be stopped. Although the dam was soon completed, Porter’s photographs helped build government support for limiting further dam construction in the West.

Listen as Land and Lens Curator Kirsten Hoving and Professor John Elder share their thoughts about Porter’s Glen Canyon project:

https://vimeo.com/212627922

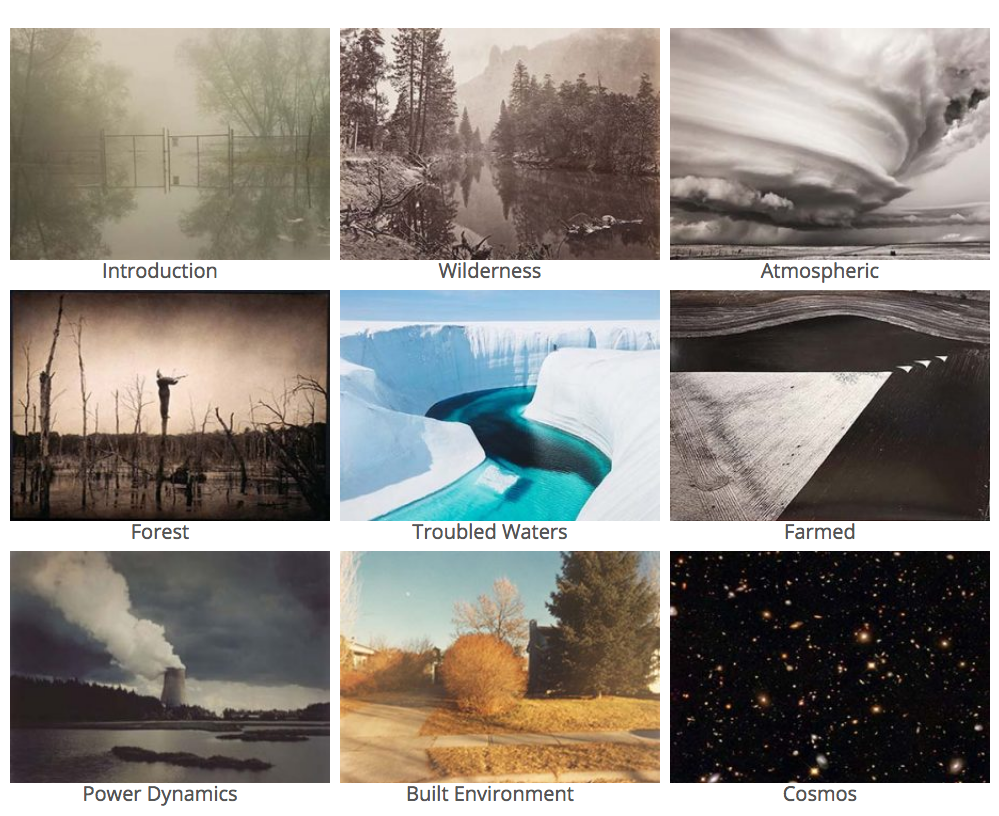

Home Page: The home page displays the eight sections of the exhibition. When you enter a section of the exhibition, tap on that category and you will be taken to the photographs in that section. There is an introduction—be sure to scroll down to see if there is a video accompanying it—and discussions of individual photographs that can be accessed by tapping on the pictures. Again, be sure to scroll all the way down on those individual pages.

Home Page: The home page displays the eight sections of the exhibition. When you enter a section of the exhibition, tap on that category and you will be taken to the photographs in that section. There is an introduction—be sure to scroll down to see if there is a video accompanying it—and discussions of individual photographs that can be accessed by tapping on the pictures. Again, be sure to scroll all the way down on those individual pages.